From leadership to luminescence: Illuminating the avenues of creativity in China's small and medium enterprise sector

Main Article Content

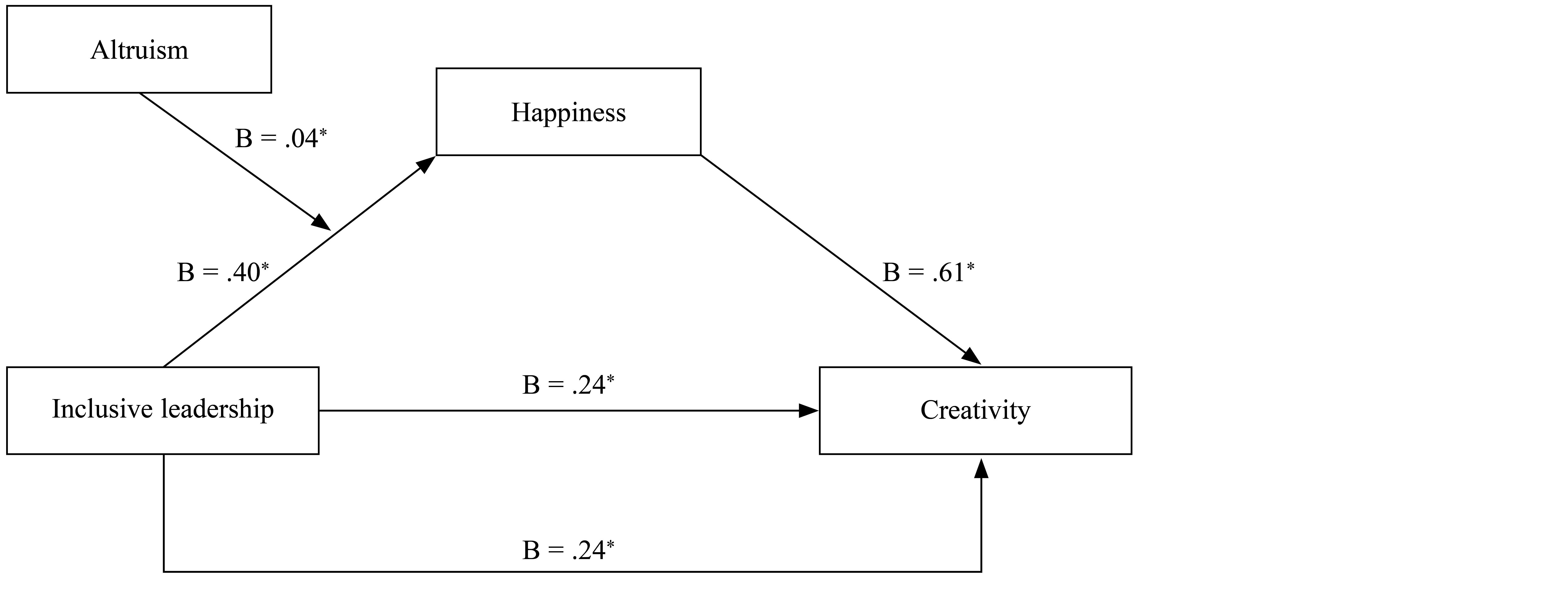

Exploring the dynamics of employee creativity in the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector is crucial for contemporary organizational studies, especially in the context of the Chinese culture. In this study we investigated the complex relationships among inclusive leadership, employees’ happiness, personal values like altruism, and creativity within China’s SMEs. The objective was to understand how inclusive leadership combined with happiness and altruism of the employees impact creative outcomes. Data were collected from 408 employees and leaders in the SME sector using a self-administered survey. We applied structural equation modeling using SMARTPLS software for analysis. We found that inclusive leadership significantly enhanced employee creativity, and this relationship was mediated by employee happiness. Employees’ altruism was a key moderator, intensifying the effects of inclusive leadership on employee creativity. Theoretically, this research fills gaps in understanding leadership, employees’ happiness, personal values, and creativity in an SME context. Practically, our findings emphasize the importance of nurturing inclusive leadership and focusing on employee well-being in guiding SMEs toward innovation and sustainable growth amidst evolving challenges.

In the current worldwide cutthroat business climate, employees are the most important factor in an organization's success. Not only do they provide operating power, but they also push innovation in an organization (Guo et al., 2021). This is even truer for small and medium enterprises, where limited resources and greater uncertainties necessitate that employee creativity underpins the development of unique and cost-effective strategies. In the small or medium enterprise, creativity drives innovation by enabling the organization to adapt swiftly to market trends and overcome resource constraints through novel solutions. As per the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are businesses with fewer than 250 employees (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2005). While 3M’s development of post-it notes and Google’s policy of encouraging employees to devote 20% of their time to engaging in creative thinking (Ahmad et al., 2022) highlight the importance of employee innovation in large corporations, SMEs rely even more heavily on employee creativity because of their limited resources and need for agile responses to market demands. Employees who have accumulated deep knowledge of the organization through years of experience and continuous learning often contribute to practical and cost-effective innovations (Imran et al., 2018) that are novel and difficult to imitate, giving a competitive advantage (Fu et al., 2022). A creative workforce generates an agile organization that is responsive to customer trends, and in which staff engagement and retention are enhanced (Nigusie & Getachew, 2019).

In the SME sector, creativity is transformative because of their unique challenges, such as limited financial resources, smaller market reach, and higher vulnerability to market fluctuations, as well as their unique opportunities like greater flexibility, closer customer relationships, and the ability to implement innovative ideas rapidly (Ahmad et al., 2021; Mahmood et al., 2021). Where resources are scarce and uncertainties are higher (Mahmood et al., 2021), the creativity of employees becomes a driving force for the SME to innovate. With agility and a culture saturated in creativity, the SME can easily catch hold of market trends (Ghimire et al., 2021). But nurturing creativity in an organization is no easy feat. The hierarchical structure and the emphasis on efficiency can easily hamper creative expression (Azeem et al., 2021). Approaches such as fostering open communication, encouraging innovation, and establishing safe brainstorming spaces work together to stimulate creativity (Fu et al., 2022).

Leadership style, particularly inclusive leadership, whereby an open, diverse, and trust-centered workplace environment is fostered, is crucial for employee creativity by enhancing collective intelligence and innovation (Kuknor & Bhattacharya, 2022). However, the impact of the style of leadership varies with psychological factors and organizational climate (Deng et al., 2022). Employee happiness is pivotal for converting inclusive leadership into creative outcomes, which depend on individual participation and innovation performance (Khan & Abbas, 2022). Furthermore, employees’ personal values, like altruism, can significantly affect workplace dynamics, amplifying or diminishing the effectiveness of leadership in promoting creativity (Loi et al., 2011). The backdrop formed by China’s mixed values of Confucianism, social collectivism, and modern strategies, along with the special context of China’s SME sector and its contribution to the country’s economy and innovation, offers a unique opportunity for studying how leadership styles interact with personal values and affect employee outcomes (Robu, 2013). Understanding these interactions is crucial in the context of China’s SME sector, which is of particular importance to the country’s economic vibrancy and innovation (Zhang et al., 2020). The rapid growth and competitive character of this sector make it important to learn how leadership and personal values such as altruism predict creativity.

There are insights to be gained from existing research on leadership and creativity, but still gaps remain. Thus far, few studies have been conducted to examine the functions of inclusive leadership in SMEs (Javed et al., 2019) or its manifestation in the cultural context of China where Confucian values of harmony, respect, and collective welfare, as well as modern elements of individualism and competition, might affect the dynamics of employee creativity and happiness in distinctive ways. Additionally, the role of employee happiness as a mediator, moderated by personal values like altruism, is a neglected area in leadership theories. Due to these existing gaps in knowledge, in the current research we investigated how leadership style and individual values affect creativity within an SME from a culturally sophisticated perspective. This knowledge is vital for leaders of organizations, including leaders of SMEs, to harness the creative potential of their workforce and drive innovation in today’s competitive business landscape.

Method

Participants and Procedure

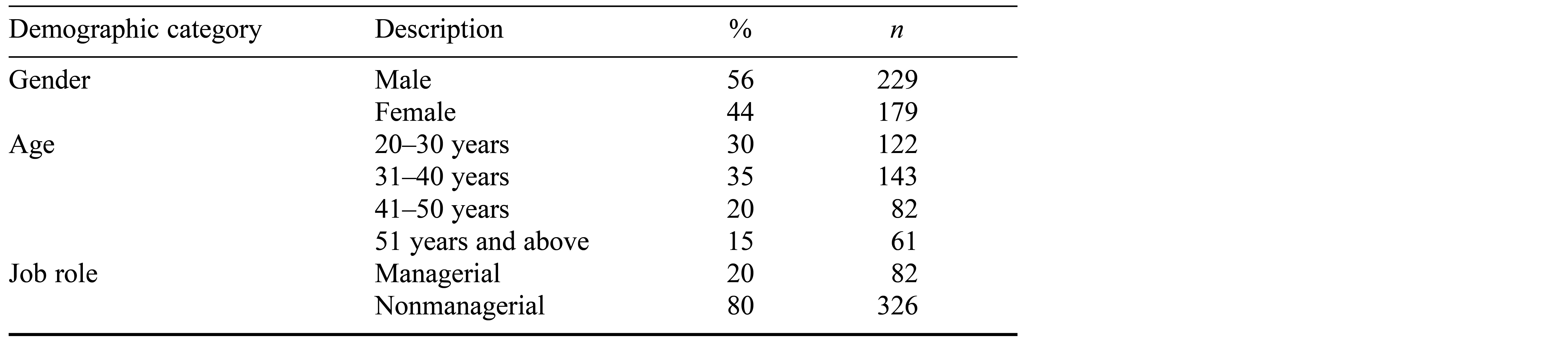

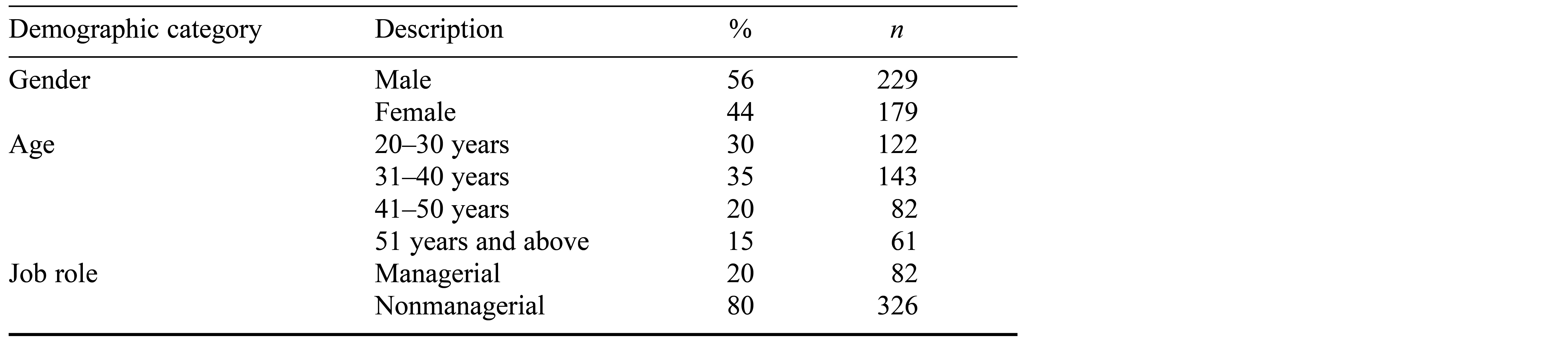

A multistage sampling process was employed to identify 16 SMEs in Hangzhou and Shenzhen, which were chosen according to the industry’s importance, size of the workforce, and annual revenue. The final criterion was the industry’s relevance to China’s economic priorities and innovation potential. We assessed relevance by considering factors such as the industry’s contribution to gross domestic product, its alignment with national development goals, and its capacity for technological advancement and job creation. The participants were 408 employees, a number that exceeded the sample size of 377 obtained by specifying a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error on a sample-size calculator (https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html). The participants’ gender, age, and job role distribution are set out in Table 1. Precisely because of the categorical nature of these demographic variables, means and standard deviations are not pertinent; these statistics are meaningful for continuous data, where they can represent central tendency and variability, but not for categorical data, which merely classifies individuals into distinct groups without a numerical hierarchy or range.

The SMEs were contacted to explain the study objectives by using formal means of communication. By taking these steps we also aimed to create an environment of trust and transparency. We adhered to the Helsinki Declaration to guarantee confidentiality and anonymity (Ahmad et al., 2024). We also asked for informed consent from participants before we proceeded with the survey. The process of data collection was carried out through a paper-based survey, which also contained an introduction to the investigation topic, with the explanation that the aim was to enrich SME research. No compensation was offered to participants. The participants were also debriefed at the end of the process. To minimize social desirability and common method variance, we assured respondents of confidentiality and encouraged honest responses. Moreover, we employed a three-wave data collection strategy and multisource data approach with different sources providing data on predictors and criterion variables. This, along with the use of validated scales, mitigated potential bias. Our three-wave data collection approach involved first collecting data on inclusive leadership practices, then on employee happiness and altruism, and finally on creative engagement from supervisors.

Table 1. Sample Demographics

Measures

As some of the measures used were originally developed in languages other than Chinese, we employed a professional translation and back-translation process. Qualified bilingual experts proficient in both English and Chinese and with extensive experience in psychological and organizational research conducted the translation and back-translation to ensure accuracy and cultural relevance.

We used a self-administered survey, with items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. To measure inclusive leadership, we used the nine items from the scale developed by Carmeli et al. (2010), which has been validated in various contexts. An example of an item from this scale reads “My manager is attentive to new opportunities to improve work processes.”

For employee happiness, we employed five items from García del Junco et al. (2013). An example from this scale is “The organizational climate of my SME is good.”

Employee altruism was measured using a four-item scale extracted from Lin (2007). A representative item from this scale is “I enjoy helping colleagues by sharing my knowledge.”

Lastly, for employee creativity, we turned to the work of Farmer et al. (2003). Their scale consists of four items to measure the opinion of an immediate supervisor/manager regarding the engagement of an employee in creativity. A sample item that epitomizes this scale is “Before using the current method, this employee tries new ideas or methods.”

Results

Initial Results

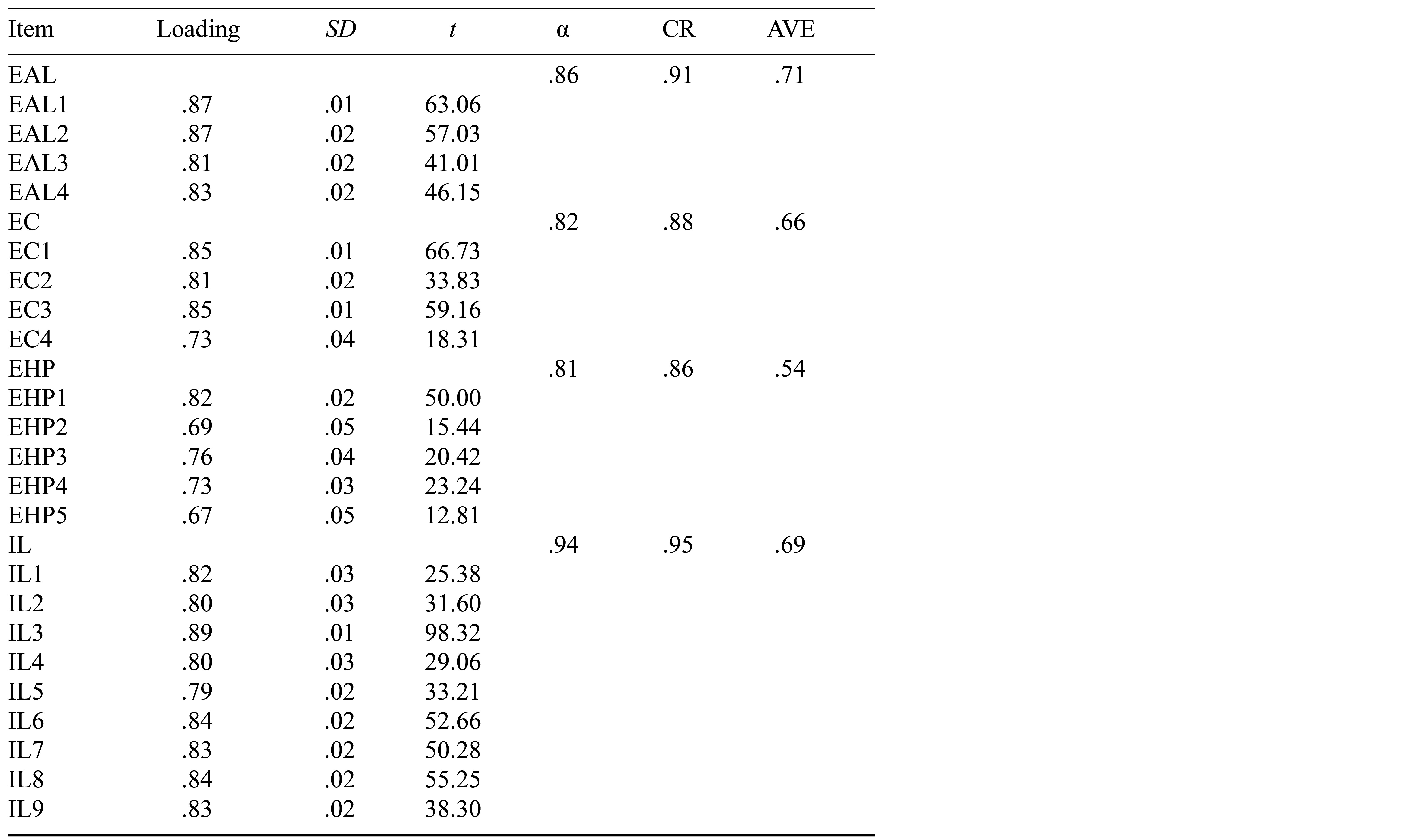

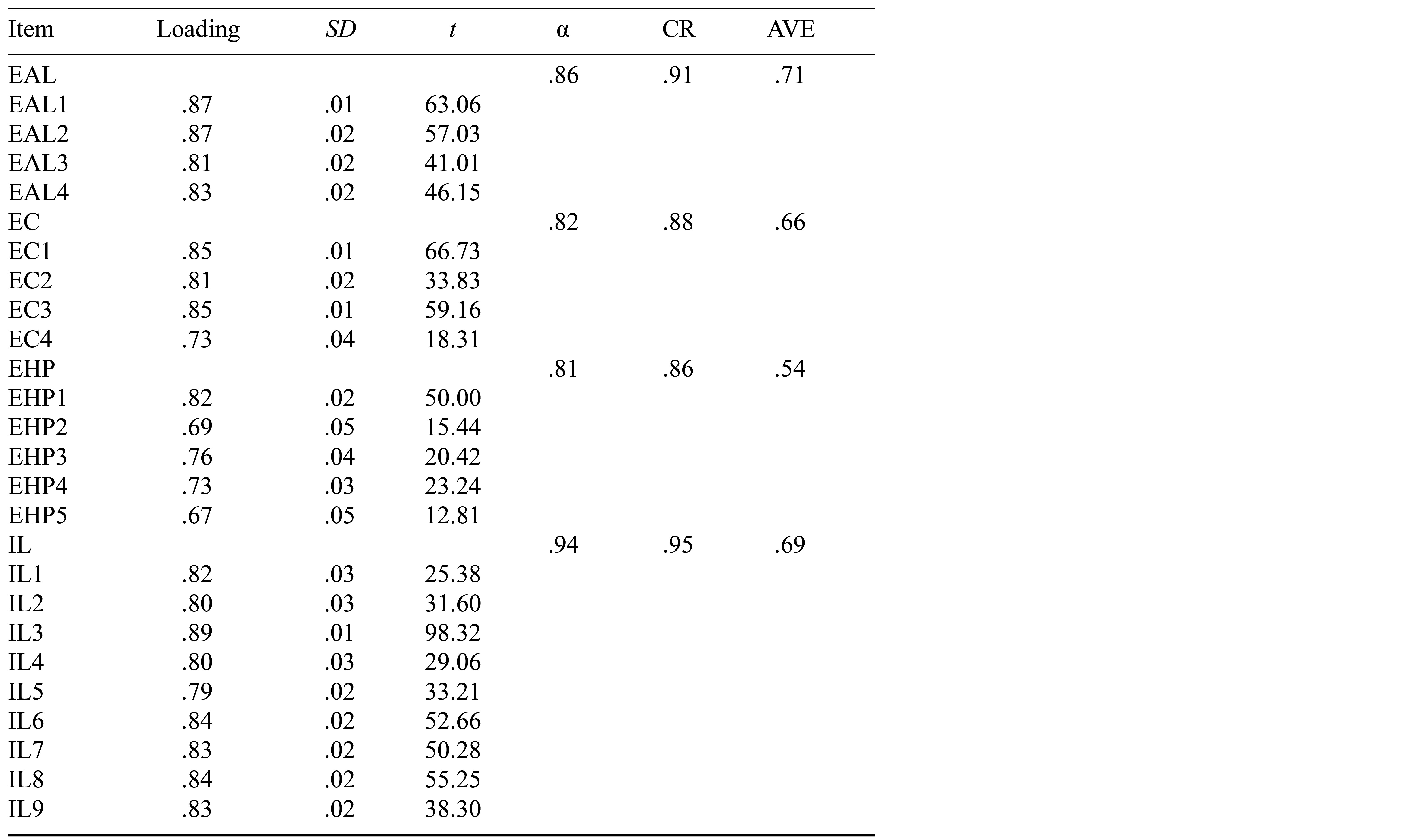

Our analysis began with evaluation of the robustness of the measurement model (Table 2), focusing on confirmatory factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Employee altruism showed high internal consistency, with all items having significant loadings. The average variance extracted (AVE) affirmed the validity of this variable. Employee creativity demonstrated similar rigor in reliability and composite reliability. The four items for employee creativity each showed solid associations and the AVE affirmed its validity. Employee happiness showed good internal consistency, with an AVE slightly lower than the previous two variables, but acceptable. Inclusive leadership scored highest of all variables in reliability metrics. The AVE affirmed its validity. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the measurement model.

Table 2. Robustness Test of the Measurement Model

Note. CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted; EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

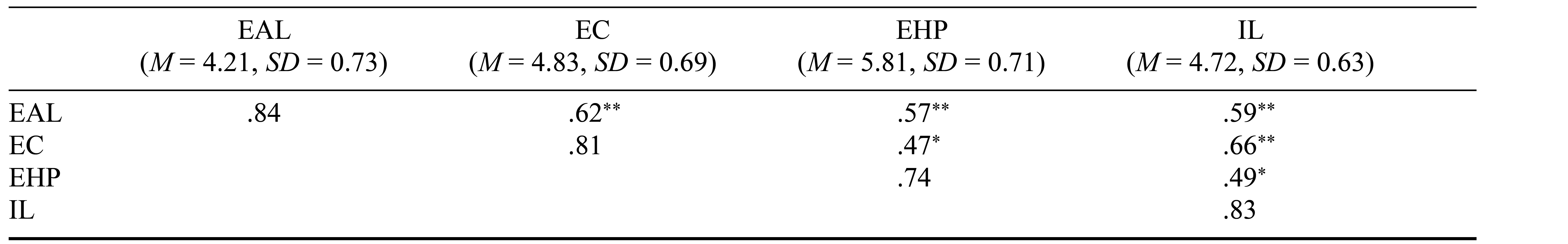

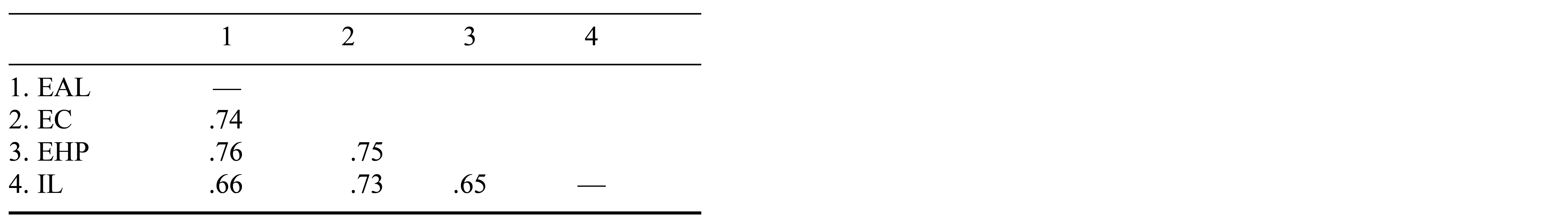

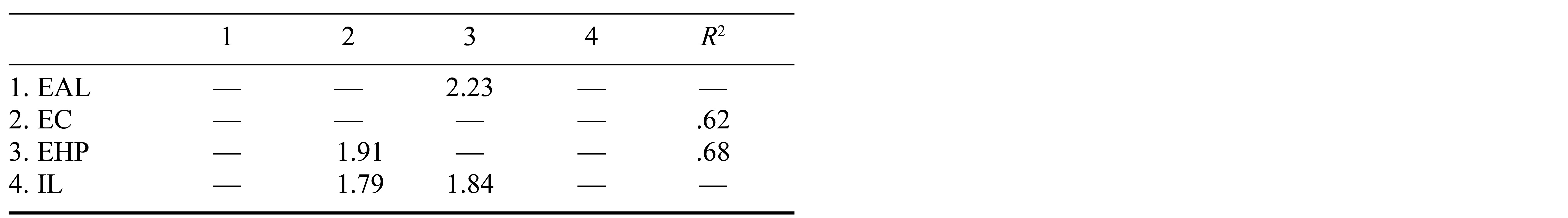

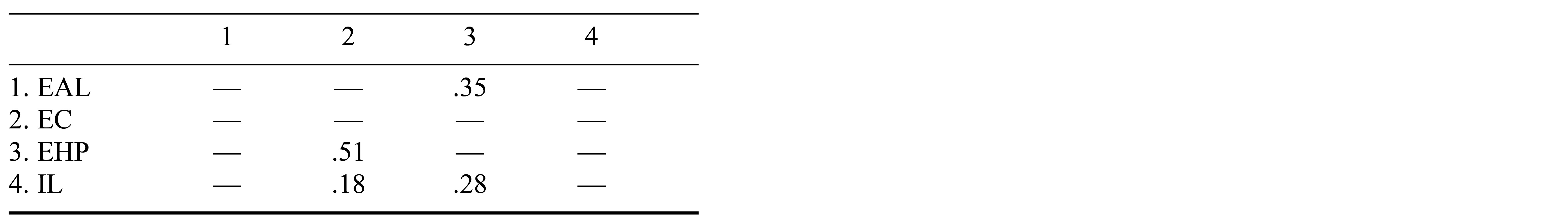

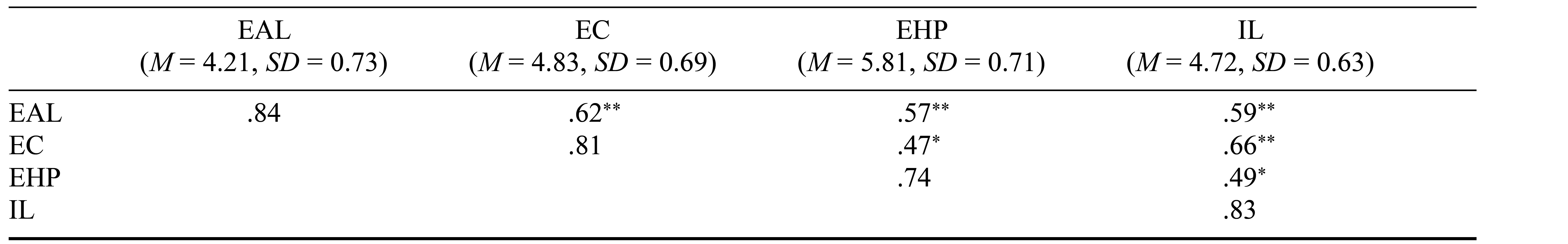

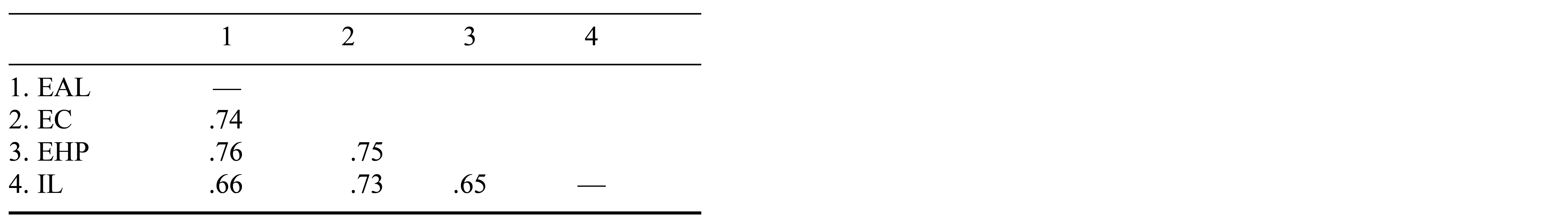

Tables 3 and 4 show results for the relationships between the variables, the divergent validity of the variables, and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratios. These data confirm the divergent and discriminant validity, indicating well-defined distinct constructs.

Table 3. Correlations and Divergent Validity of Study Variables

Table 4. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratios of Study Variables

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

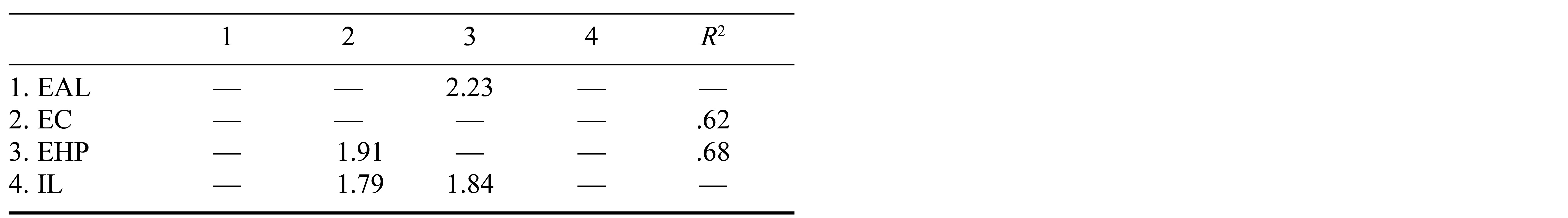

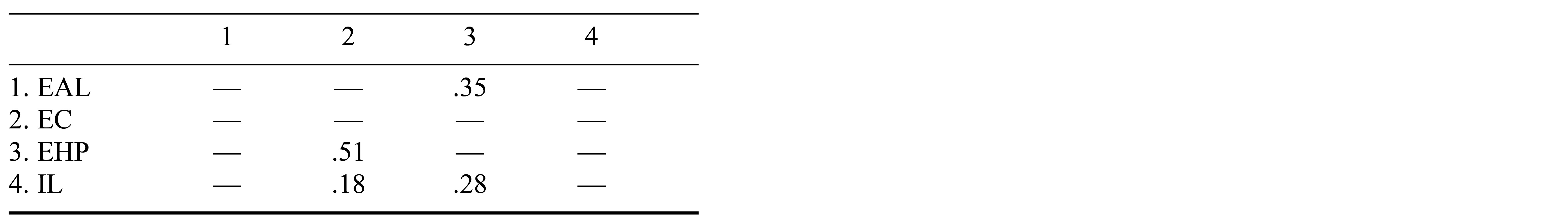

Table 5 reveals the variance inflation factor values, indicating no multicollinearity issues in our model. The coefficient of determination values showed a satisfactory degree of variance explanation for the dependent variable. In Table 6, the ƒ-squared values are presented, signifying the effect sizes of the variables. Employee altruism, employee creativity, employee happiness, and inclusive leadership each exhibited medium to large effect sizes, underlining the practical significance of our findings.

Table 5. Variance Inflation Factor and Coefficient of Determination Values

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Table 6. ƒ 2 Values

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Main Results

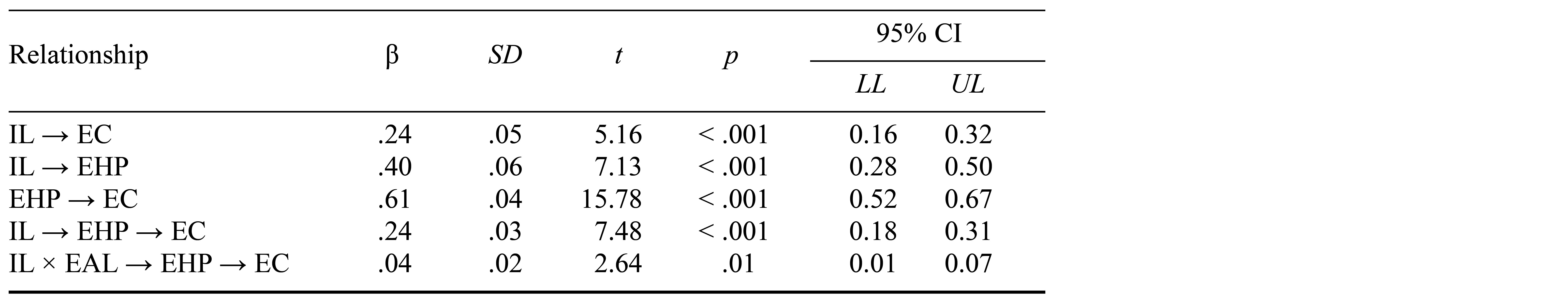

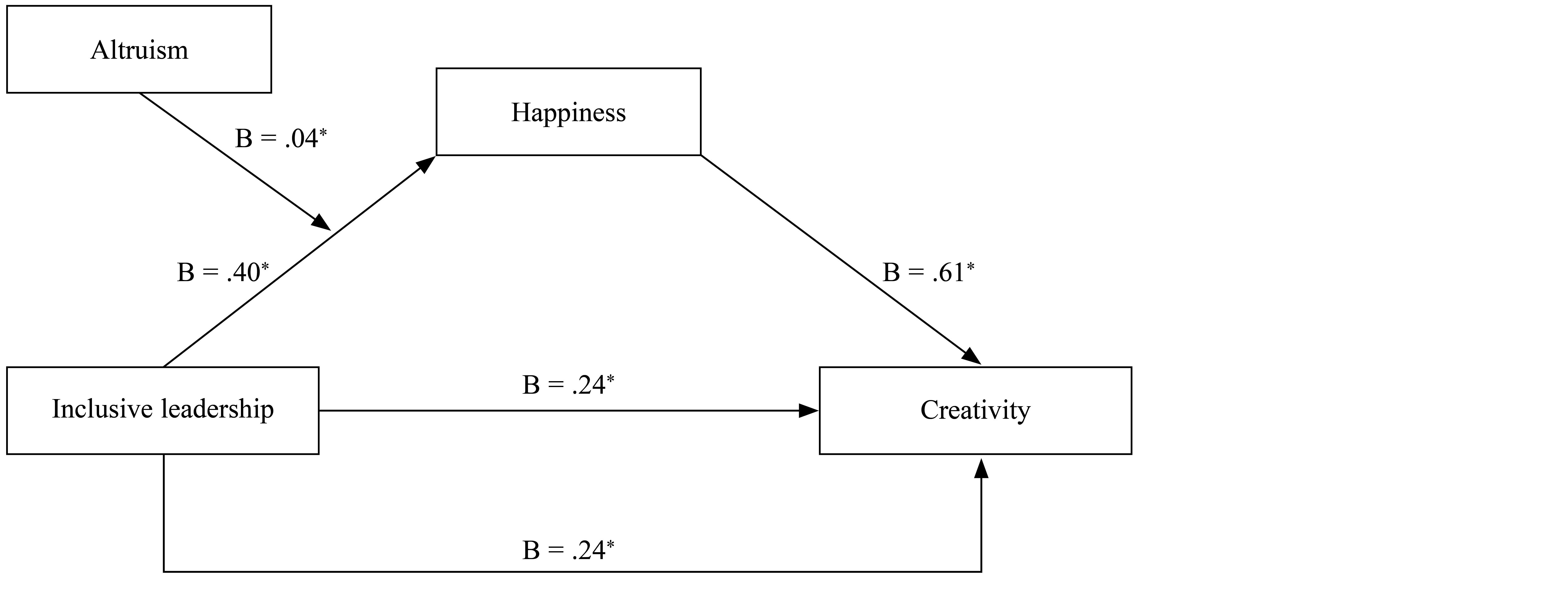

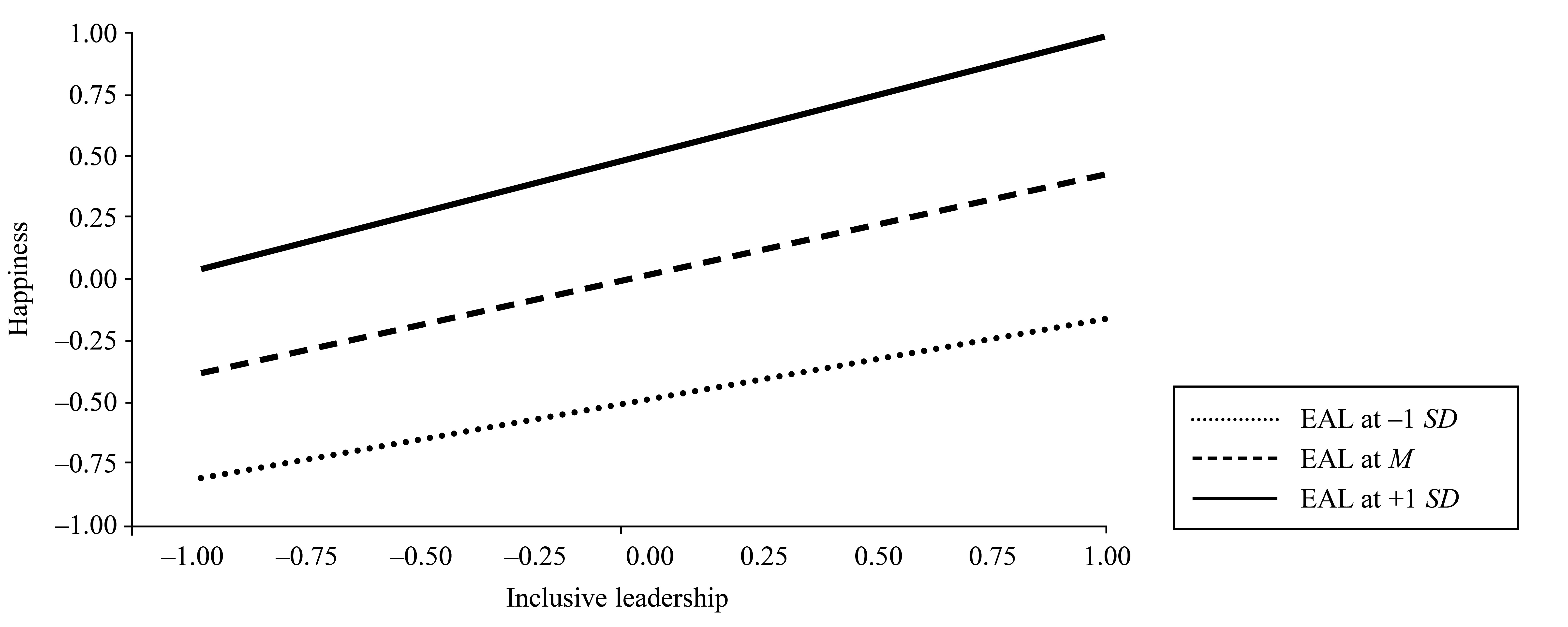

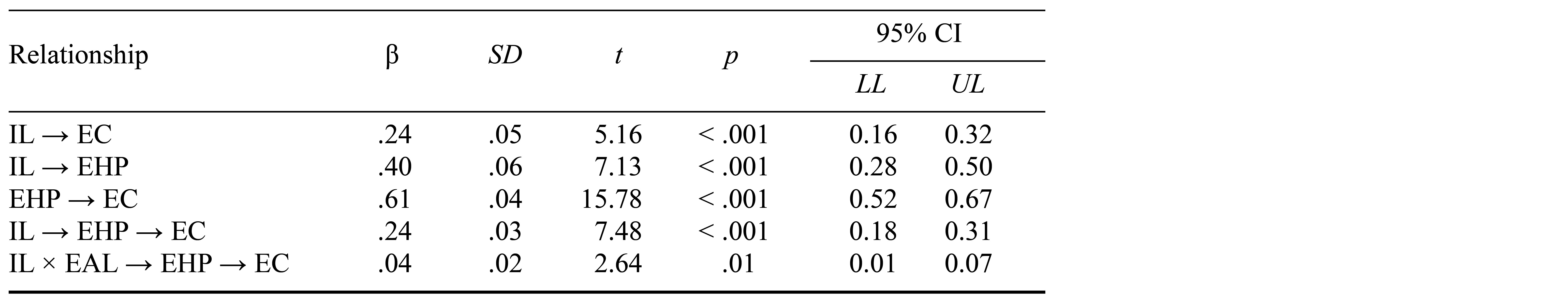

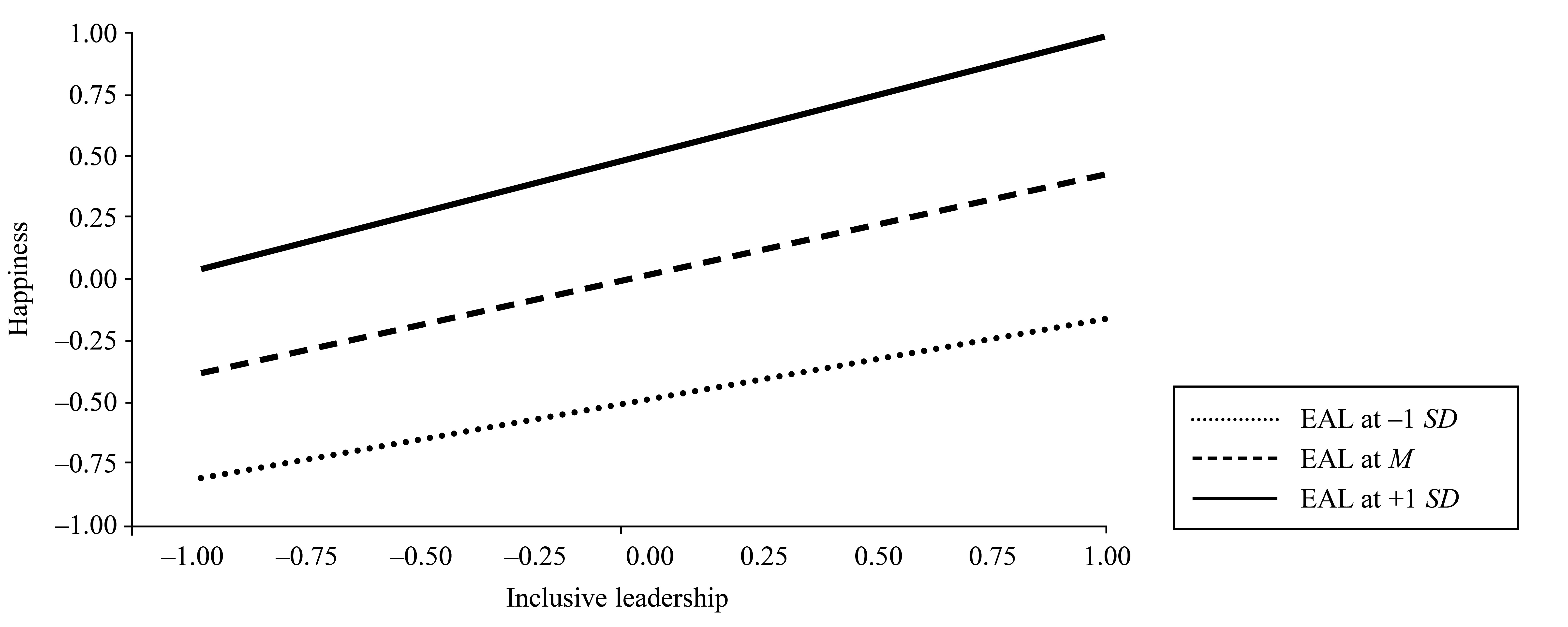

As shown in Table 7, our structural analysis gave us important insights to be considered for hypothesis validation. According to this analysis of direct effects, inclusive leadership had a significant predictive effect on employee creativity and there was also a significant positive predictive effect of inclusive leadership on employee happiness, which supported our hypothesis. Furthermore, employee happiness was a significant mediator of the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee creativity, which confirmed our hypothesis. The moderated mediation analysis, predicting the mediated effect of inclusive leadership on employee creativity through employee happiness, substantiated the significant moderating role of employee altruism in the inclusive leadership–employee happiness–employee creativity relationship, thereby confirming our hypothesis. Figure 2 shows simple slopes analysis across levels of employee altruism. When altruism was one standard deviation below the mean, the impact of inclusive leadership on employee happiness was reduced compared to when altruism was at or above the mean. The impact of inclusive leadership was moderate at a mean level of employee altruism, whereas the impact became more substantial when employee altruism was one standard deviation above the mean.

Table 7. Hypothesis Analysis

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Discussion

Our study adds to the literature on employee creativity and leadership styles emphasizing the critical role of inclusive leadership in enhancing employee creativity. This aligns with the assertions of Ghosh (2015) and Żywiołek et al. (2022) highlighting the impact of leadership on employee outcomes. Our findings also align with those of Carmeli et al. (2010), demonstrating that inclusive leadership not only inspires but actively enables creativity. This is further supported by the application of SET, whereby an inclusive workplace environment leads to creative reciprocation by employees, which is a concept explored by Siyal et al. (2021). We investigated the relationships of inclusive leadership with employee happiness and employee creativity. Inclusive leadership fostering openness and belongingness enhances employee well-being (Choi et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2020). This enriched environment, as per SET, leads to positive reciprocity among employees through heightened emotional well-being and creativity. According to SET, the link between happiness and creativity is strengthened in workplaces where positive organizational exchanges boost trust and reciprocity, which, in turn, enhances creativity. This is in line with the observation of Li et al. (2017) that positive organizational exchanges enhance trust and reciprocity, which subsequently boosts employee creativity. The mediating role of happiness that we found in the relationship between inclusive leadership and creativity is noteworthy. Inclusive leadership first elevates happiness, which then becomes the foundation for creative output. This mediation is evident in empirical studies, such as those of Kaur and Kaur (2024) and Romão et al. (2022), suggesting a domino effect initiated by inclusive leadership. Thus, our study suggests that inclusive leadership not only predicts creativity directly but also does so indirectly by enhancing employee happiness, which then catalyzes creativity. Furthermore, altruism significantly shapes the leadership–employee creativity dynamic. Altruism, reflecting selflessness, predicts how altruistic employees perceive leadership practices, aligning their values with the inclusive leadership experience. Amplified happiness leads to greater creativity, as supported by the findings of Grant (2012) that altruistic behavior and inclusive leadership significantly enhance employee happiness, which, in turn, boosts creativity. In the context of SET, altruism transcends being simply a personal value. It deeply influences the nature of organizational exchanges. Altruistic employees view leadership gestures as affirmations of their values, enhancing their happiness and creative contributions. This nuanced understanding of the role of altruism in organizational dynamics shows that, as we had hypothesized, altruistic tendencies strengthen the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee creativity via employee happiness.

Theoretical Implications

Our study enhances understanding of how leadership styles, personal values, and organizational outcomes interact in a culturally rich context like China’s SME sector. In our study we have broadened the conceptual scope of how leadership predicts employee creativity. Considering the role of employee happiness as a mediator between inclusive leadership and employee creativity introduced a novel aspect, emphasizing the importance of employees’ emotional well-being in organizational outcomes. Incorporating a personal value such as altruism as a moderator in the framework of leadership emphasizes the significance of individual characteristics in organizational studies. Our focus on China’s SMEs provides a unique cultural perspective, contributing to a more geographically and culturally diverse understanding of leadership and organizational behavior. In our study we addressed gaps in the literature, particularly regarding the role of employee happiness and personal values in the context of leadership within the SME sector in China.

Practical Implications for China’s Small and Medium Enterprise Sector

Our findings suggest that prioritizing inclusive leadership can significantly boost employee creativity and innovation. Traditionally, performance metrics in China’s SMEs have focused on productivity, efficiency, and financial outcomes. However, our study emphasizes that employee happiness, which extends beyond these traditional metrics, can unlock creative potential. This suggests the need for initiatives that promote employee well-being and a sense of belonging. Considering personal values in recruitment and team building can enhance the positive effects of an inclusive environment. Recognizing the unique blend of traditional and modern values in China, tailored leadership approaches that align with cultural values are essential. Our study offers a roadmap for using an inclusive leadership style to leverage employee happiness and personal values, such as altruism, to achieve competitive advantage in a dynamic business environment.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although our study offers valuable insights, its generalizability across all SMEs in China may be limited because of cultural and regional diversity. The three-wave data collection strategy could introduce recall biases and the use of self-reporting might mean that the responses were subject to social desirability biases. The sample size, though sufficient, represents a small fraction of China’s vast SME sector. In future studies, researchers should conduct studies in diverse geographical areas within China and consider additional mediators or moderators, like organizational culture or employee empowerment. Other personal and cultural values beyond altruism should be investigated, and mixed-method approaches can provide deeper insights. Examining other stakeholder relationships in SMEs could further enrich understanding of organizational creativity.

Conclusion

Our study in China’s SME sector highlights the critical role of inclusive leadership in fostering a creative environment, enhanced by employee happiness and personal values like altruism, and, hence, the need to prioritize leadership development focusing on employee well-being and integrating personal values as key strategies for success. Our findings offer practical guidance for SMEs to foster innovation and growth, emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach to leadership that integrates emotional, cultural, and personal facets.

References

Table 1. Sample Demographics

Table 2. Robustness Test of the Measurement Model

Note. CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted; EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Table 3. Correlations and Divergent Validity of Study Variables

Table 4. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratios of Study Variables

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Table 5. Variance Inflation Factor and Coefficient of Determination Values

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Table 6. ƒ 2 Values

Note. EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

Table 7. Hypothesis Analysis

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; EAL = employee altruism; EC = employee creativity; EHP = employee happiness; IL = inclusive leadership.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Hyerin Lee, Department of Hotel Management, Kyunghee Cyber University, 26 Kyungheedae-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130-739, Republic of Korea. Email: [email protected] or Heesup Han, College of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05006, Republic of Korea. Email: [email protected]