Depression is a multifaceted mental health disorder, often manifested through chronic affective states of sadness, despair, and anhedonia (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As a global public health concern, depression afflicts millions of people worldwide and significantly diminishes their quality of life (World Health Organization, 2017). The alleviation of depressive symptoms through nonpharmacological means has become a focal point of psychological research, with volunteer service frequently cited as a beneficial intervention (Musick & Wilson, 2003). The underlying premise is that volunteerism, by promoting social connection and a sense of purpose, can mitigate the isolating and debilitating effects of depression, a premise supported by empirical studies predominantly situated within Western contexts (Post, 2005).

However, the efficacy and experience of volunteer service are not universal, with the nature of volunteer organizations playing a crucial role. In Western societies, where volunteer organizations are common, volunteering often improves mental health by making people feel good about their actions (Borgonovi, 2008). In contrast, volunteer services in China are often in the nascent stages of development, which may lead to inconsistent quality in the volunteer experience (Hu, 2021). Motivations for volunteering in these settings frequently diverge from the altruistic ethos, often driven by the pursuit of personal gain or compliance with institutional mandates, which could attenuate the psychological benefits (Grönlund, 2011).

The discrepancy between the motivations for and outcomes of volunteer service in China raises questions about cultural congruence. The family-centric culture of China emphasizes familial obligation over public altruism, a divergence from the individualistic orientation of many Western societies where much of the existing volunteerism research has been conducted (Yan, 2016). The misalignment between the cultural ethos and the structure of volunteer activities can potentially lead to a cultural dissonance, affecting the impact of volunteerism on an individual’s mental health (Chirkov et al., 2003).

Hence, I endeavored to elucidate the intricacies of volunteer service within the sociocultural fabric of China by examining its interrelation with depression. This study is predicated on the premise that the culturally contingent nature of volunteerism may moderate its efficacy as a therapeutic modality. I critically examined the applicability of the positive correlation widely documented in Western contexts between volunteerism and enhanced mental well-being, within the distinct cultural contours of Chinese society. Furthermore, I contemplated the adaptation of volunteer programs to align more congruently with the familial values that predominate in many Asian cultures. By doing so, I sought to augment the inherent therapeutic potential of volunteer activities, potentially offering a culturally sensitive approach to mental health interventions.

Volunteer Participation and its Influence on Depression Within Nascent Social Organizational Structures

Volunteer participation is a dynamic social activity where individuals engage in unpaid work to benefit others (Wilson, 2000). The literature on volunteerism posits it as a salutary endeavor, enhancing individual mental health through community engagement and the fostering of altruistic satisfaction (Piliavin & Siegl, 2007). Yet, the extant research predominantly reflects volunteers’ experiences within mature nonprofit sectors, leaving a gap in understanding the effects within the nascent social organizations of rapidly modernizing societies (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). In such contexts, the impetus for volunteerism often shifts from intrinsic to externally motivated incentives, raising questions about the authenticity of the volunteering experience and its psychological outcomes (Wuthnow, 2012).

Contemporary studies within the emerging social organizations of rapidly modernizing societies have predominantly focused on older adults to evaluate volunteerism’s mental health impacts. For example, H.-L. Yang et al. (2022) utilized data from the 2013 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study and demonstrated that volunteerism chiefly promotes well-being among older adults through positive emotional experiences. Y. Liu et al. (2020), drawing from the 2014 Chinese Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS), proposed that volunteer activities not only improve older adults’ self-rated health but also foster a more positive aging perspective. Wu et al.’s (2023) further analysis using the 2018 CLASS data accentuated the susceptibility of older adults to depression, intensified by declining physical capabilities and shrinking social networks after retirement. Volunteerism, as an integral social activity, plays a crucial role in alleviating depression by enhancing social engagement. This beneficial connection was particularly noted during crises, as Chan et al. (2021) highlighted the critical role of involving older adults in volunteerism for maintaining mental health amidst the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the complex relationship between volunteerism and depression in older adults presents challenges. Jiang’s (2022) research, based on the 2014 and 2016 CLASS datasets, indicated that formal volunteerism does not consistently improve mental health, with impacts varying according to community settings and individual choices. Notably, in older adults, a higher prevalence of community-level formal volunteering was found to be associated with more depressive symptoms, indicating the operational challenges volunteer services encounter within dynamic social infrastructures.

Compounding this issue, engaging in volunteerism across all age demographics within dynamic social infrastructures can be fraught with operational challenges, possibly leading to experiences devoid of the anticipated altruistic fulfillment (Omoto & Snyder, 2002), as observed among older adults (Jiang, 2022; Wu et al., 2023). The dichotomy between the expected psychological benefits of volunteering and the actualized experiences of participants in these settings necessitates a reevaluation of the nexus between volunteerism and well-being (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Notably, the cultural dissonance experienced by volunteers, when juxtaposed against family-centric values that are predominant in many Asian societies, can become a source of internal conflict and psychological distress (C. Chen, 2016).

Furthermore, in the context of societies grappling with social involution and heightened competition, the very act of volunteering (typically associated with personal growth and societal contribution) may paradoxically morph into a stressor, contributing to the burden of depressive symptoms among individuals (Schwartz et al., 2010). This inversion of roles, where volunteerism potentially exacerbates rather than alleviates depression, suggests a complex interplay between individual motivations, organizational maturity, and societal expectations (Lu & Gilmour, 2004).

Delving into the cognitive models of family culture provides a lens through which to understand these phenomena, particularly the cognitive dissonance that arises when public-spirited volunteerism clashes with the collectivist familial obligations ingrained within certain cultures (Triandis, 2001). This framework posits that the internal cultural conflicts engendered by participating in volunteer activities within such societies can precipitate or intensify depressive symptoms, thus challenging the predominantly positive narrative of volunteerism in the domain of mental health (Oyserman & Lee, 2008). Therefore, I proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Volunteer participation will be positively associated with depression within nascent social organizational structures.

The Role of Familial Trust

Familial trust is conceptualized as the intrinsic confidence and belief in the integrity and solidarity inherent within family relationships, serving as a fundamental element for the functional dynamics and cohesion of family systems (L. Liu, 2008). In the interstice of psychological well-being and social participation, familial trust has emerged as a construct of profound significance, with research delineating its role as a bulwark against the multifaceted strains of depression. The theoretical underpinnings of this phenomenon are grounded in the social support literature, which posits that one’s network of family relationships provides a critical emotional buffer that can mitigate stressors and enhance mental health resilience (Pierce et al., 1996). This buffering effect is particularly relevant in the realm of volunteering within emergent social organizational structures, where the potential for psychological discomfort is amplified by the unpredictability and transitional nature of these settings (Walsh, 2003).

Delving deeper, the literature suggests that the dimension of familial trust transcends mere amelioration of depressive states. It is instrumental in fostering a milieu where psychological rewards from volunteerism are amplified through familial validation and encouragement (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). Such dynamics are critical in the social capital discourse, where the trust inherent within family units can extend to broader social networks, enhancing the subjective well-being derived from altruistic engagements (Helliwell & Putnam, 2004).

The role of familial trust also becomes pivotal when considered against the backdrop of internal conflict within the volunteer’s psyche, arising from the dichotomy between self-oriented aspirations and the collectivist orientation of volunteer work. Scholars have argued that a solid foundation of familial trust serves to allay such dissonances, promoting alignment with communal goals and diminishing the conflict between self-interest and public good (Cohen & Wills, 1985). This concept is further illuminated in contexts where social structures are in flux, suggesting that familial trust can act as a stabilizing force amidst the volatilities of nascent social organizations (Uslaner, 2002).

As a mediator between the individual’s inner world and societal expectations, familial trust is posited to reconcile the internal cultural conflicts that may arise from volunteer activities. This harmonizing role of familial trust is particularly salient in mitigating depressive outcomes, thereby reinforcing its critical function in the psychological processes associated with volunteer participation (Kagitcibasi, 2005). Therefore, I proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Familial trust will attenuate the link between volunteer participation and depression within nascent social organizational structures.

The Nexus of Familial Trust and Autonomy

Autonomy is delineated as the capacity of an individual to make informed and voluntary decisions, free from external coercion or undue influence (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Autonomy, a vital component of well-being, is considered a prerequisite for engaging in voluntary activities that are genuinely satisfying and beneficial to mental health (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Without autonomy, individuals may find themselves trapped in a cycle of obligatory service, wherein familial pressures supersede personal choice, potentially leading to internal conflict and increased stress (B. Chen et al., 2015). Thus, in the absence of autonomy, even strong familial bonds may fail to alleviate the psychological toll associated with volunteer activities.

Conversely, when individuals possess autonomy, familial trust can act as a catalyst, propelling them from the comfort of established social bonds into the broader community in a psychologically rewarding manner (Hammack, 2018). This safety net allows autonomous individuals to venture into the realm of volunteerism with the assurance that their familial relationships provide a supportive backdrop, which is crucial in incipient social organizational structures where roles and expectations may be less defined (Janoski & Wilson, 1995).

However, for those lacking autonomy, familial trust may inadvertently contribute to a reluctance toward civic engagement, thereby perpetuating feelings of obligation and burden (Matsuba et al., 2007). Autonomy has emerged as a critical mechanism that allows familial trust to fulfill its potential as a protective factor in the psychological experience of volunteering (Haivas et al., 2012). This calls for a nuanced understanding of how familial trust can either anchor an individual within a secure zone of well-being or tether them to a domain of unfulfilled expectations and psychological malaise. Therefore, I proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Within nascent social organizational structures, familial trust will attenuate the link between volunteer participation and depression among individuals with high autonomy.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study, which involved secondary analyses of data from the China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey (CLDS; He, 2014), which is a comprehensive biennial longitudinal study, meticulously observing the evolving dynamics and interactions within the social structure, labor force, and familial settings of villages and urban communities across China. Exclusively targeting labor-force participants aged between 15 and 64 years, the CLDS encompasses a geographically diverse sample from 29 provinces and major cities, deliberately excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Xizang, and Hainan. The survey methodology employs a rigorously structured multistage, stratified probability sampling technique, proportionate to the size of the labor force, known as probability proportional to size sampling. This approach ensures a representative and comprehensive dataset. Unique to the CLDS is its rotating sample tracking method, which adeptly accommodates China’s rapidly changing socioeconomic landscape while effectively integrating the advantages of both cross-sectional and longitudinal survey designs. In the 2018 iteration, after data cleansing to exclude missing and outlier variables, 16,348 valid samples were analyzed, providing robust insights into China’s labor force trends and patterns. As this study involved secondary analyses of publicly available, deidentified data, ethics approval was not required.

Measures

Dependent Variable: Depression

The measurement used in the CLDS for depression was adapted from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). The scale consists of 20 items distributed across four dimensions: depressive affect (seven items, e.g., “I felt that everything I did was an effort”), somatic symptoms (seven items, e.g., “My sleep was restless”), positive affect (four reverse-scored items, e.g., “I was happy”), and interpersonal difficulties (two items, e.g., “I felt that people disliked me”). Participants are prompted to identify the number of days in the preceding week during which these symptoms occurred by using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (0–1 days) to 4 (5–7 days). The measurement encompasses a spectrum of depressive symptoms, such as irritability over minor annoyances, appetite disturbances, entrenched sorrow irrespective of social support, feelings of inferiority, concentration difficulties, pervasive sadness, lethargy, pessimism, self-denigration, anxiety, insomnia, social withdrawal, solitude, perceived hostility from others, existential dissatisfaction, tearfulness, gloom, social alienation, and thoughts of life cessation. In this study the measure demonstrated a high degree of reliability, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of .95.

Independent Variable: Volunteer Participation

In consideration of the evolving climate of volunteering within China, volunteer participation is typically initiated in an organized fashion by social organizations, which may be state directed or grassroots in origin (Hu et al., 2023). In the CLDS, the participants were asked one question: “In the past year, how often have you participated in activities of nonprofit organizations (some organizations may charge a small membership fee) such as volunteer groups (e.g., social workers, volunteers)?” with responses recorded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (daily).

Moderating Variables: Familial Trust and Autonomy

Familial trust is pivotal in fostering functional interpersonal relationships and cooperative interactions among family members, thereby reinforcing familial bonds in China (Yan, 2016). In the CLDS, participants were asked a single question: “How much do you trust your family members?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely distrust) to 5 (completely trust).

The CLDS explored autonomy by asking participants to assess their perceived autonomy, specifically their self-perceived ability to direct their own life path. The aim was to capture the spectrum of perceived autonomy. Participants were asked the following question: “Some people feel they can completely choose their own life, while others feel powerless about what happens to them. How would you rate your freedom to choose your own life?” Answers were made on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no choice at all) to 10 (a great deal of choice).

Instrumental Variable: Willingness to Engage with Marginalized Populations

I incorporated willingness to engage with marginalized populations as an instrumental variable. An instrumental variable is a type of variable used in statistical analysis that is not directly related to the outcome of interest (in this case, depression), but is related to the endogenous explanatory variable (in this case, volunteer participation). As an instrumental variable, it is used to address potential endogeneity issues, where the cause-and-effect relationship between volunteer participation and depression may be bidirectional or confounded by other variables not accounted for in the study.

Willingness to engage with marginalized populations is an individual’s propensity to initiate interaction with societal segments that are marginalized from central societal frameworks (Kurzban & Leary, 2001). The collectivist ethos and emphasis on social consonance in Chinese society suggest that willingness to engage with marginalized populations is a stable trait, influenced more by entrenched societal traditions than by transient mental health conditions (L. H. Yang & Kleinman, 2008). Therefore, willingness to engage with marginalized populations is instrumental in predicting volunteer participation rates (Lowe et al., 2019), possibly without having a direct impact on depression levels. This is exemplified in the CLDS, wherein participants’ willingness to engage with marginalized populations was gauged vis-à-vis a spectrum of marginalized groups, encompassing those experiencing depression issues, substance abuse, unemployment, gambling addiction, involvement in usurious lending, and with nontraditional sexual orientations. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (a strong inclination to engage) to 5 (a pronounced unwillingness to engage). The scale’s reliability was empirically evaluated, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .76 indicating a commendably consistent internal coherence.

Covariates

Informed by the extant literature that has elucidated factors contributing to depression, I methodically adjusted for an array of demographic and socioeconomic variables that might confound the analysis (Califf et al., 2022; Martela et al., 2023), comprising age (treated as a continuous metric), gender (0 = women, 1 = men), marital status (0 = unmarried, 1 = married), place of residence (0 = rural, 1 = urban), and the quantification of siblings beginning from a count of zero.

To assess educational achievement, participants responded to the question “What is the highest level of education you have completed?” Responses were recorded on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no formal education) to 11 (doctoral degree). To measure health, participants were prompted with “Please rate your health.” This was recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unhealthy) to 5 (very healthy). I evaluated social status with the question “Where would you place yourself on a social scale?” Responses were scored on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (lowest social stratum) to 10 (highest social stratum). The sense of security within the community was gauged with the question “How often do you think about property theft?” Answers were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (frequently). To evaluate trust in business counterparts, participants were asked “How much trust do you have in the people with whom you do business?” Responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely distrust) to 5 (completely trust).

Data Analysis

This study operationalized a quantitative analytic approach, utilizing Stata 16.0 for statistical examination. Preliminary measures included a variance inflation factor analysis to ascertain the nonexistence of multicollinearity, with a threshold mean variance inflation factor established at below 2. Following this precautionary step, the study proceeded to descriptive statistical analysis, articulating the means, proportions, and standard deviations of the variables. The subsequent phase involved deploying instrumental variable methods within a multiple linear regression framework to elucidate the relationship between volunteer participation and depression. The construct of familial trust was integrated into the model as a potential moderating variable. Further, the concept of autonomy was examined to assess its influence on heterogeneity within the sample. To reinforce the validity of the findings, robustness checks were meticulously conducted, which included adjustments for potentially omitted variables and modifications to the sample size to test the consistency of the results.

Results

Sample Characteristics

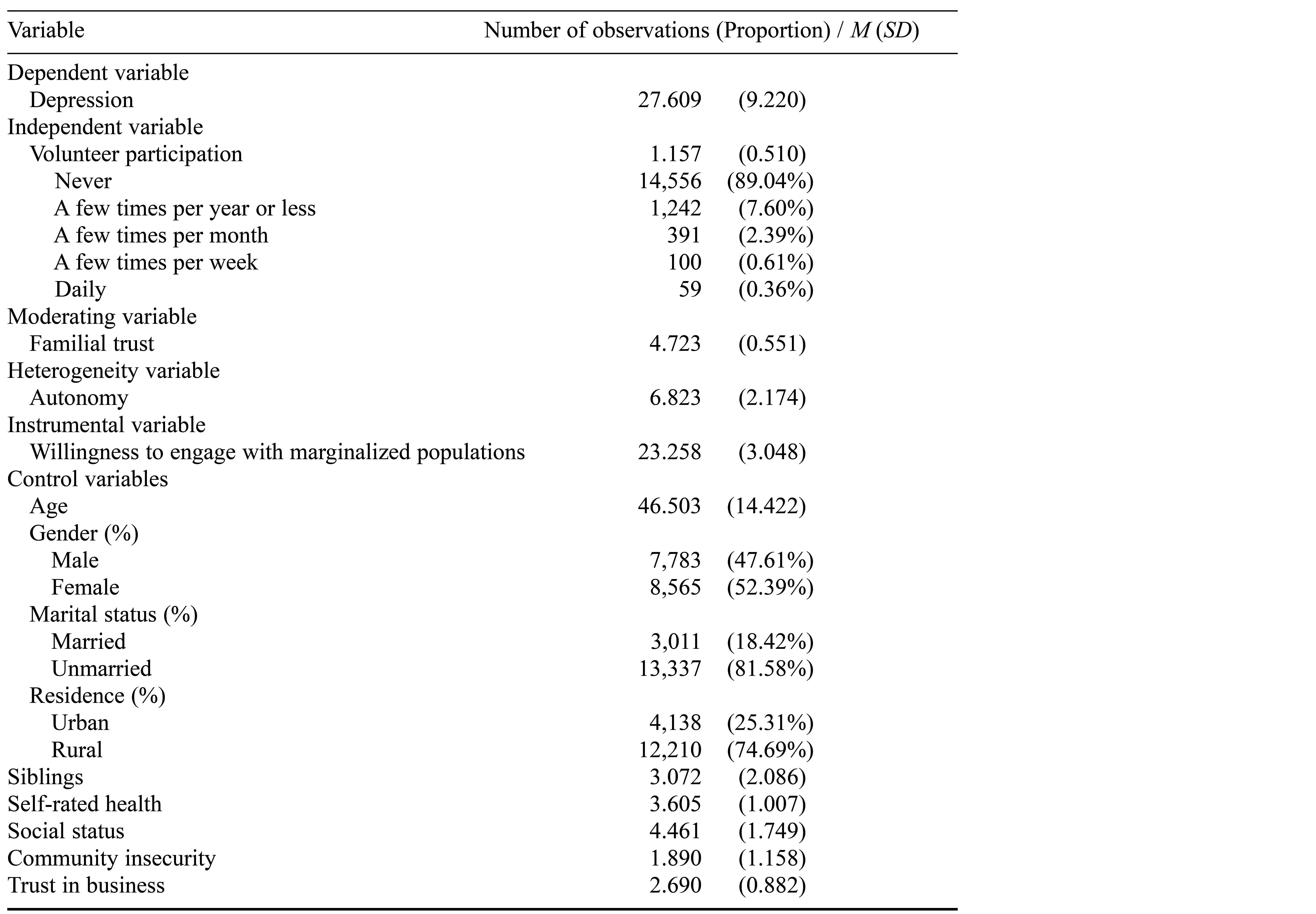

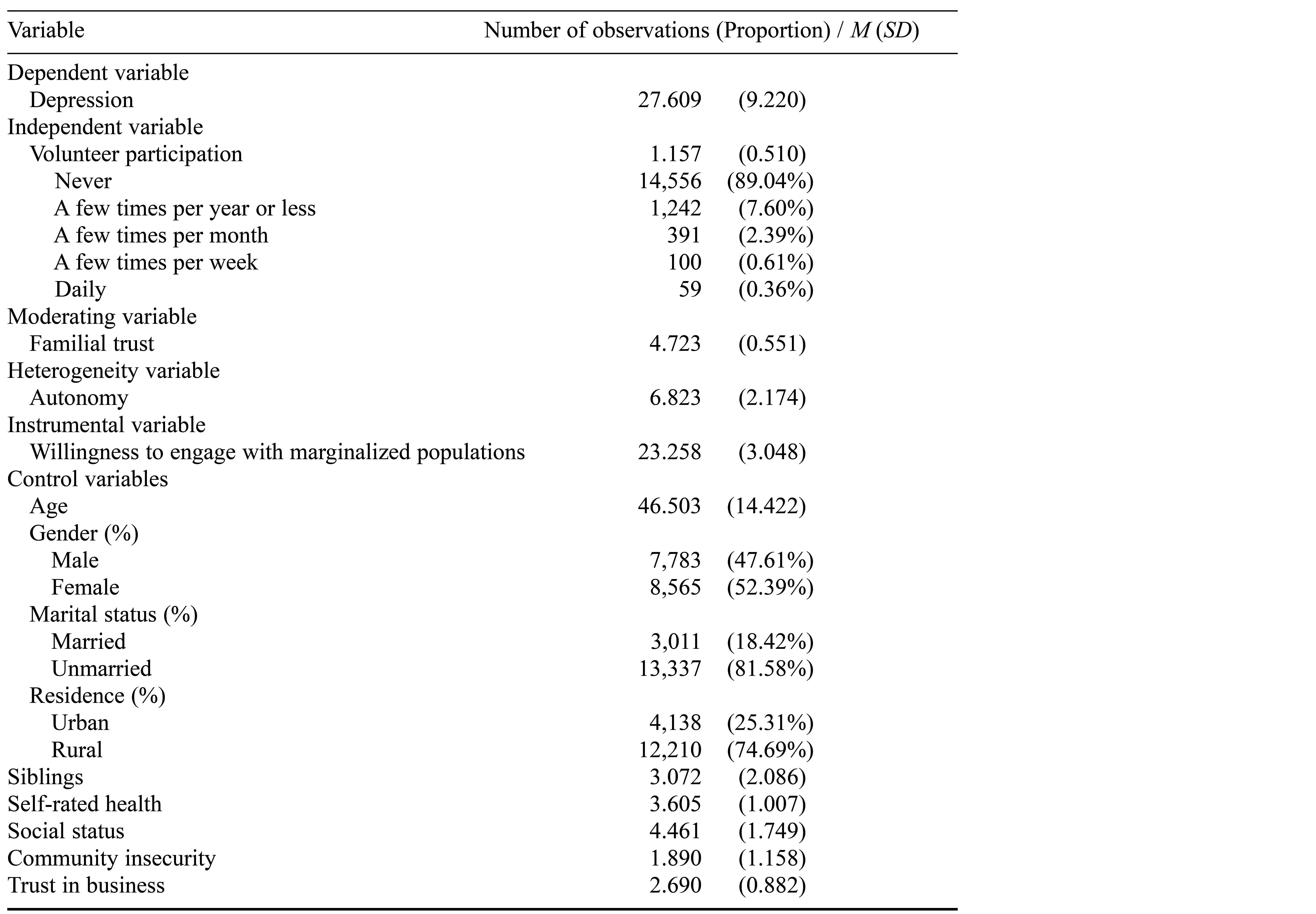

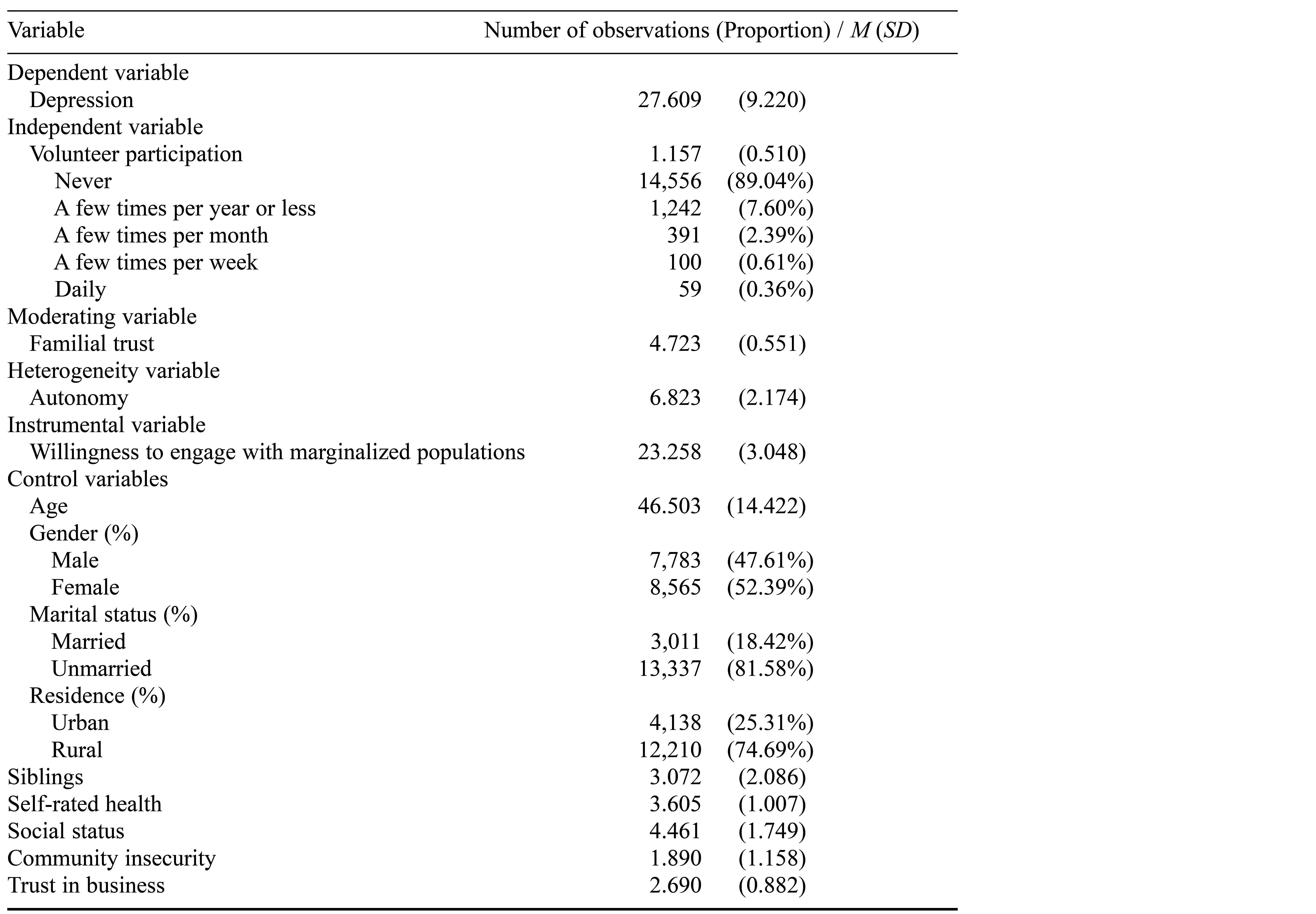

The data presented in Table 1 reveal there was a relatively low level of depression among participants. Volunteer participation was low. A robust willingness to engage with marginalized populations was apparent. High familial trust was evident, and autonomy was similarly strong, indicating the sample was confident in managing personal and communal challenges.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

The sample showed a broad age range. Gender representation was balanced. A significant majority were married and most lived in rural areas, with a smaller proportion in urban settings. Socioeconomically, the average number of siblings was over three, suggesting larger family units. Participants rated their health as good. Social status assessments trended toward a moderate level and trust in business was moderate, depicting a middle-ground stance toward commercial institutions. Respondents scored low on community insecurity, indicating varied perceptions of local stability.

Two-Stage Least Squares Regression Analysis

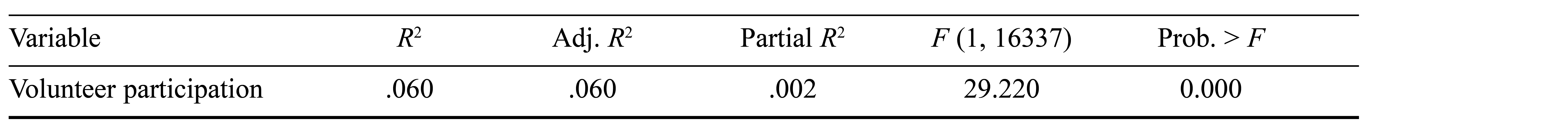

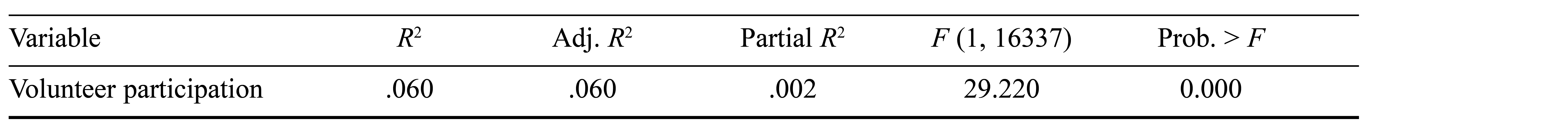

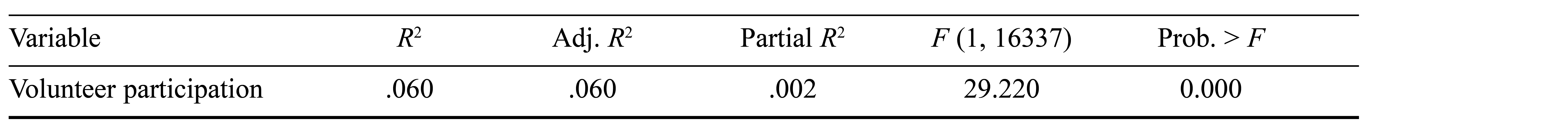

Table 2 articulates the initial regression phase within the two-stage least squares framework, revealing a statistically significant nexus between volunteer participation and the instrumental variable (willingness to engage with marginalized populations), as evidenced by an R2 value of .06. The coefficients are presented in their unstandardized form, maintaining the original scale of each variable. The instruments’ robustness was affirmed by an F statistic of 29.22, decisively exceeding the nominal threshold of 16.38 specified for the 5% Wald test denoting instrument strength.

Table 2. First-Stage Regression Statistics

Note. R2 = multiple correlation squared. Minimum eigenvalue statistic = 29.220. Size of nominal 5% Wald test (10%) = 16.38. Coefficients are presented in their unstandardized form, maintaining the original scale of each variable. This approach facilitates a straightforward interpretation of the impact that a one-unit alteration in the predictor variable has on the outcome variable.

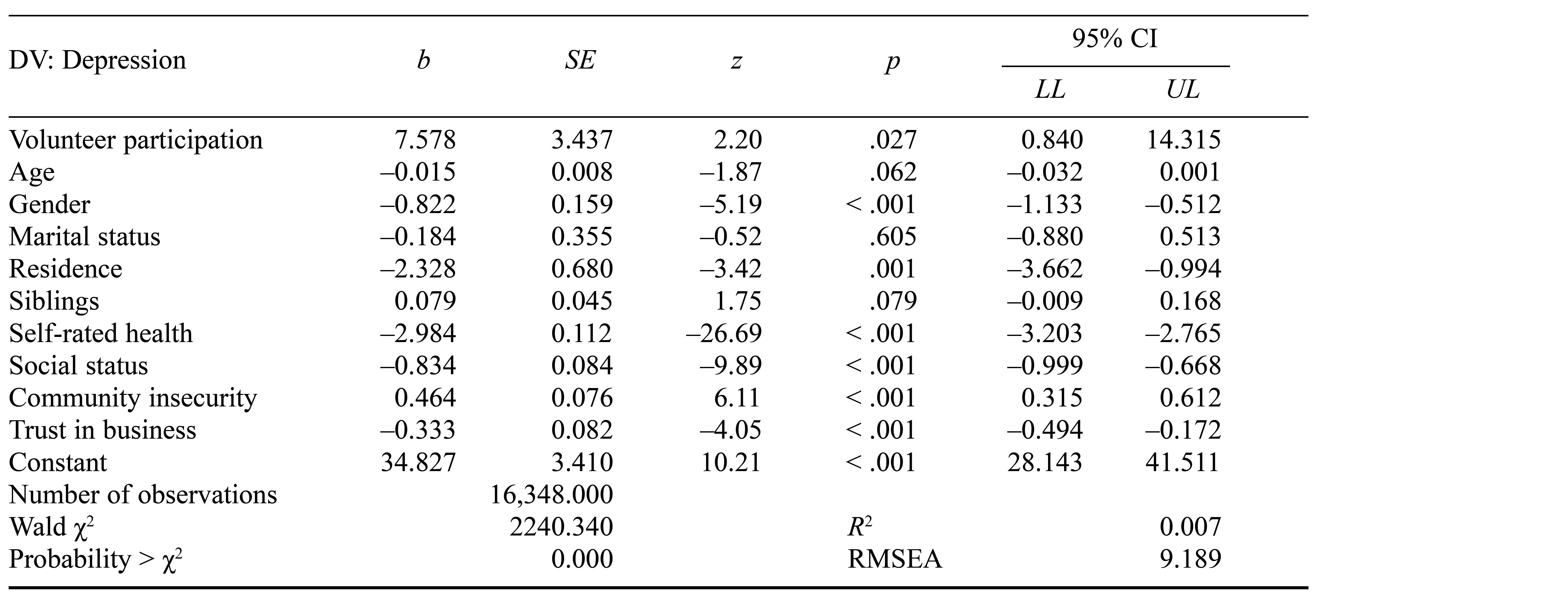

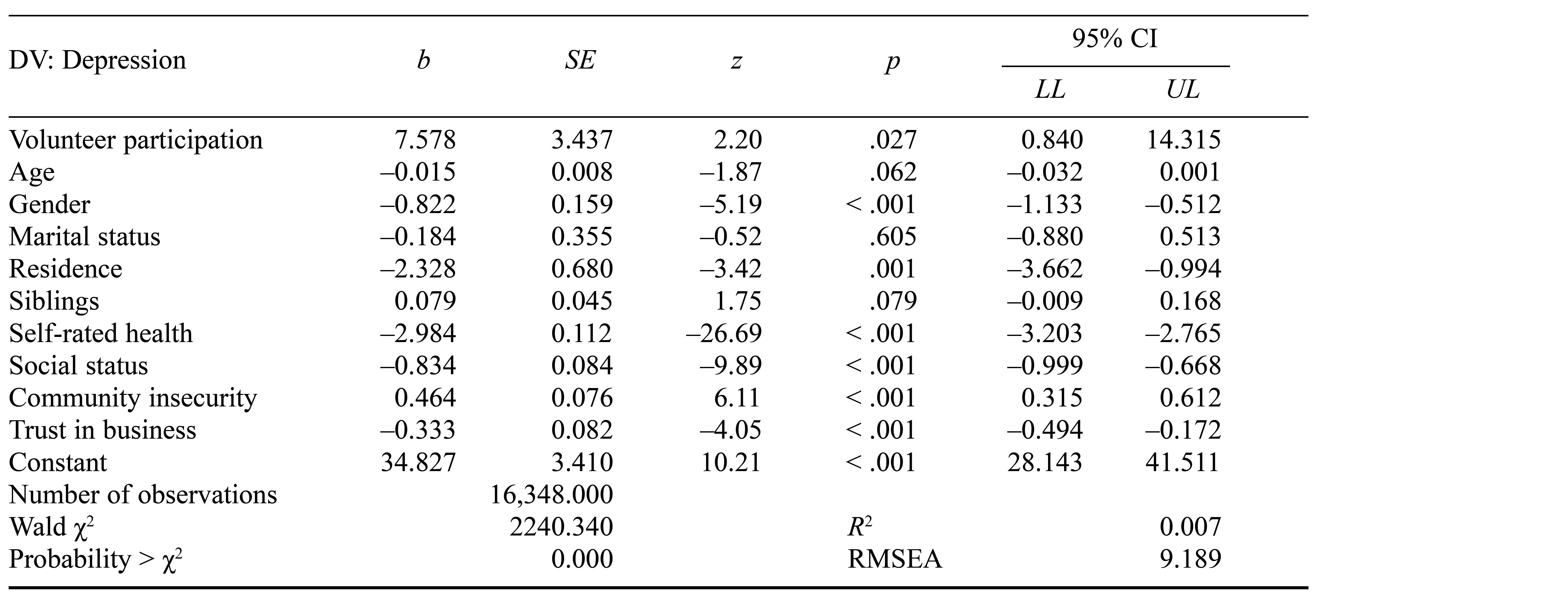

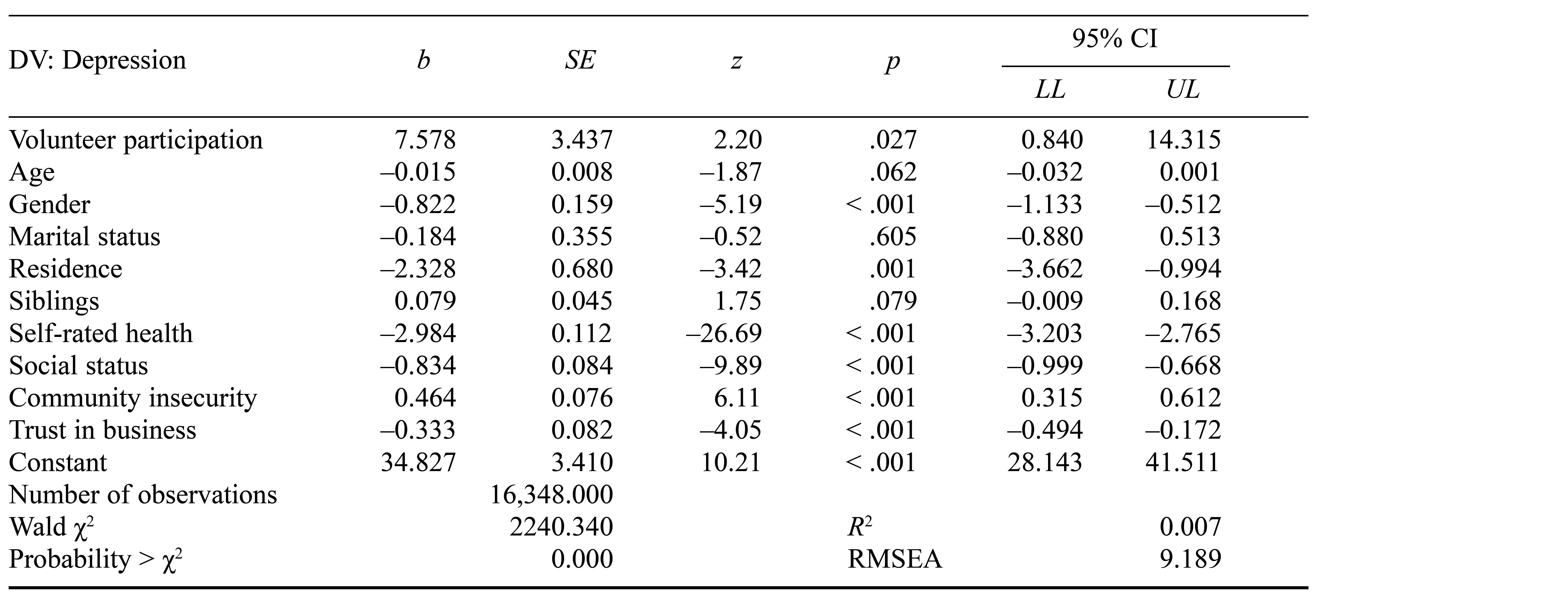

Progressing to the second-stage regression, Table 3 shows there was a discernible and positive correlation between volunteer participation and depression. This suggests an escalation in depression scores concomitant with increased volunteer participation, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 3. Two-Stage Least Squares Instrumental Variable Regression Statistics

Note. DV = dependent variable; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation. Coefficients are presented in their unstandardized form, maintaining the original scale of each variable. This approach facilitates a straightforward interpretation of the impact that a one-unit alteration in the predictor variable has on the outcome variable.

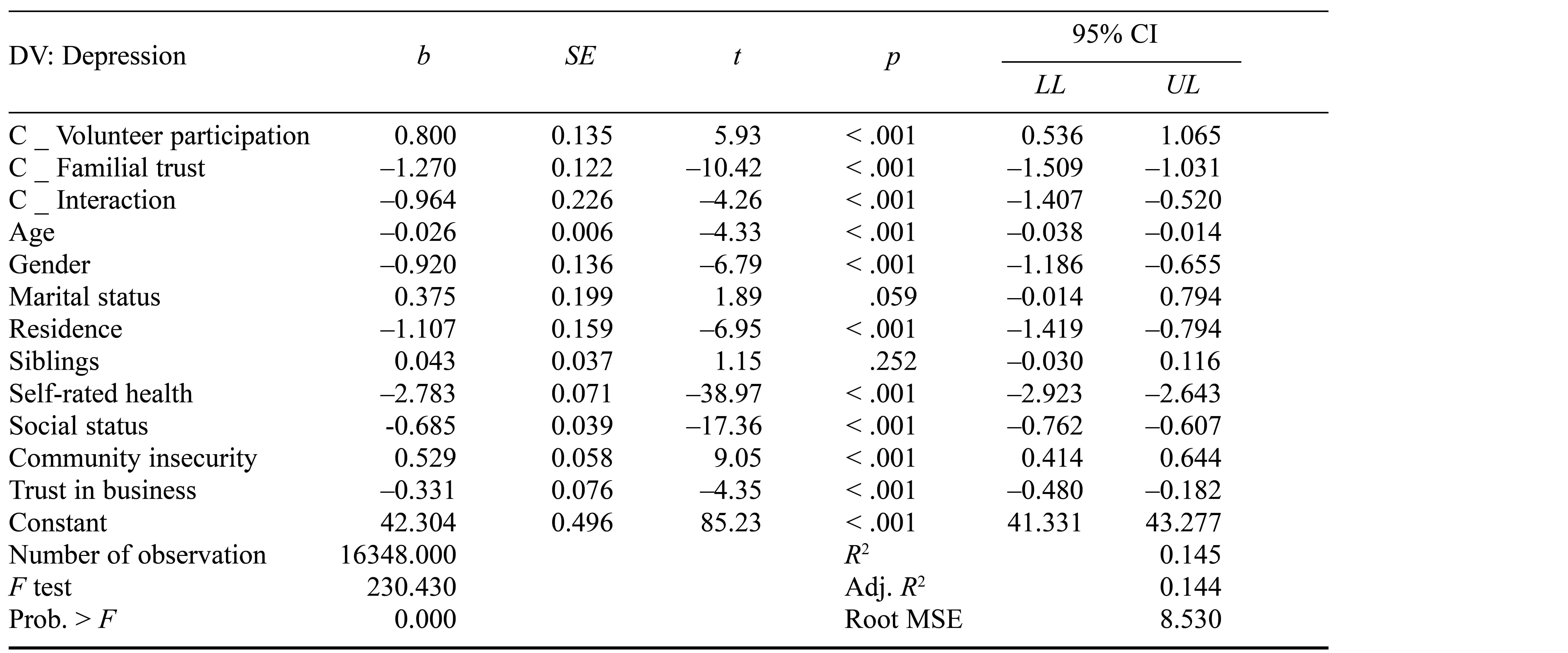

Moderation Effect Analysis

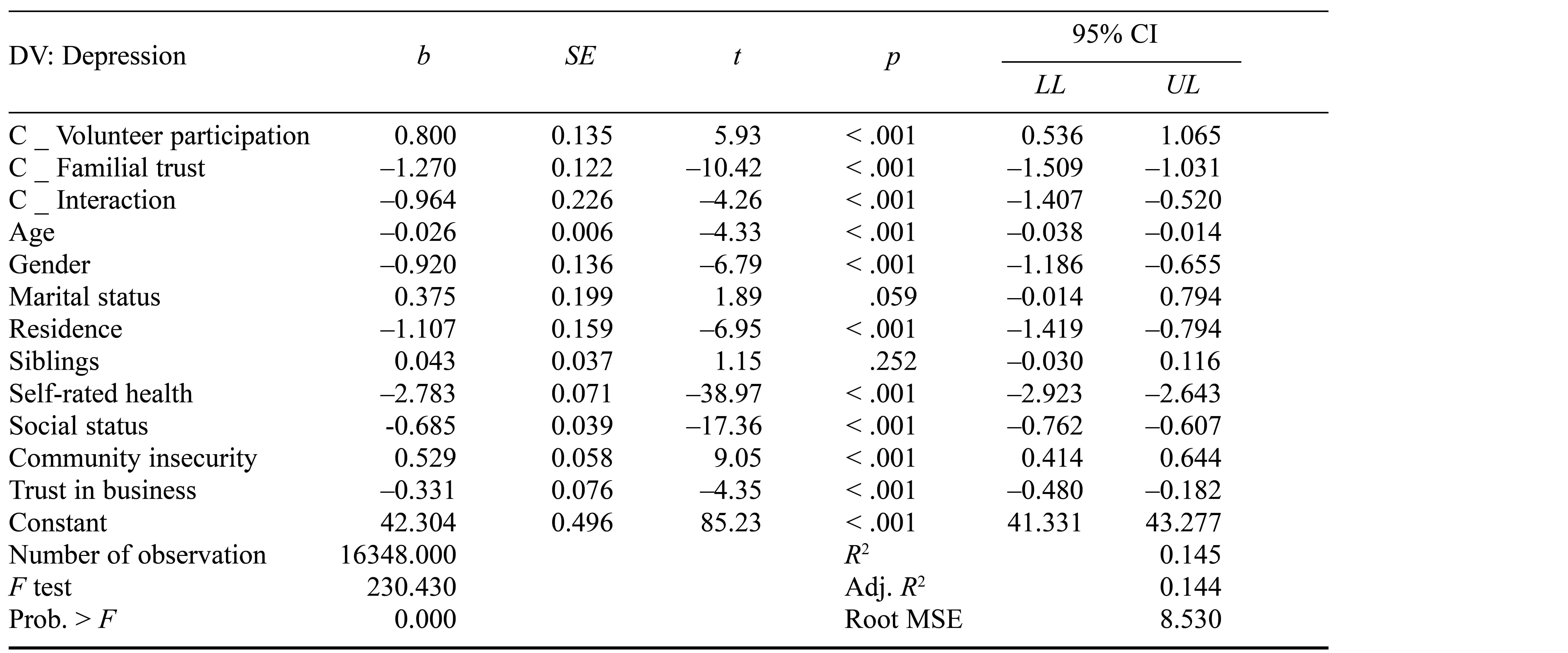

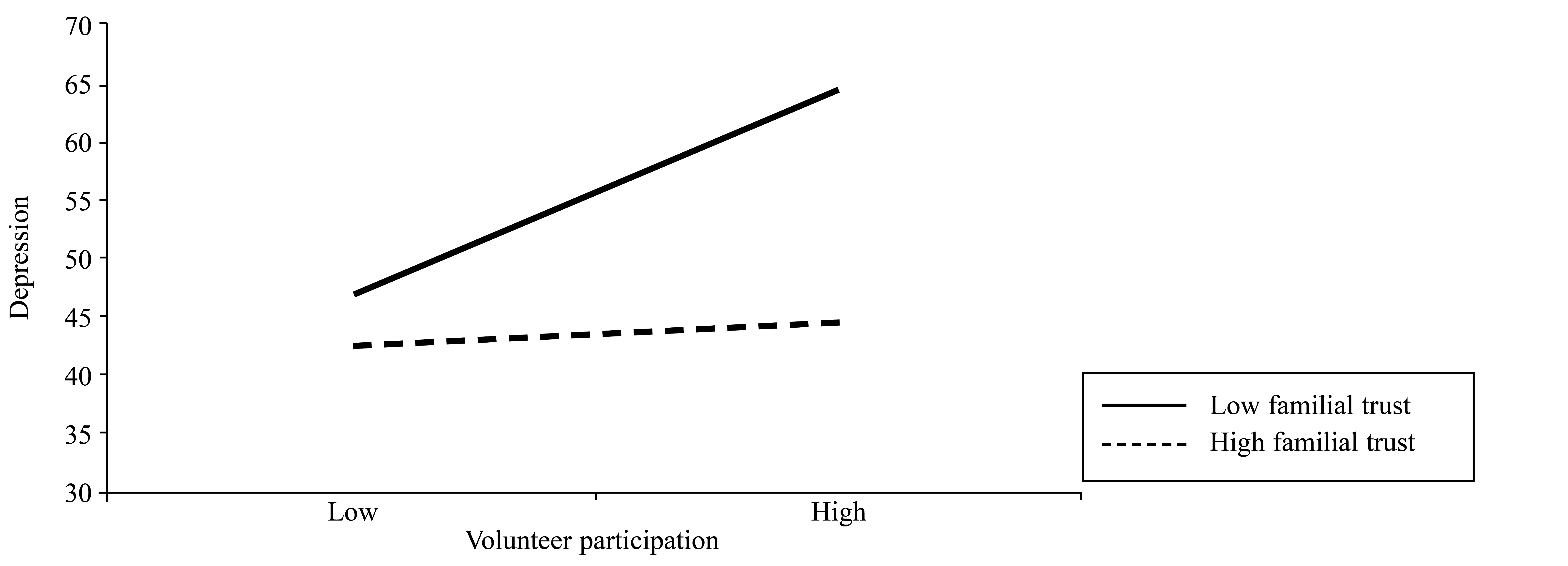

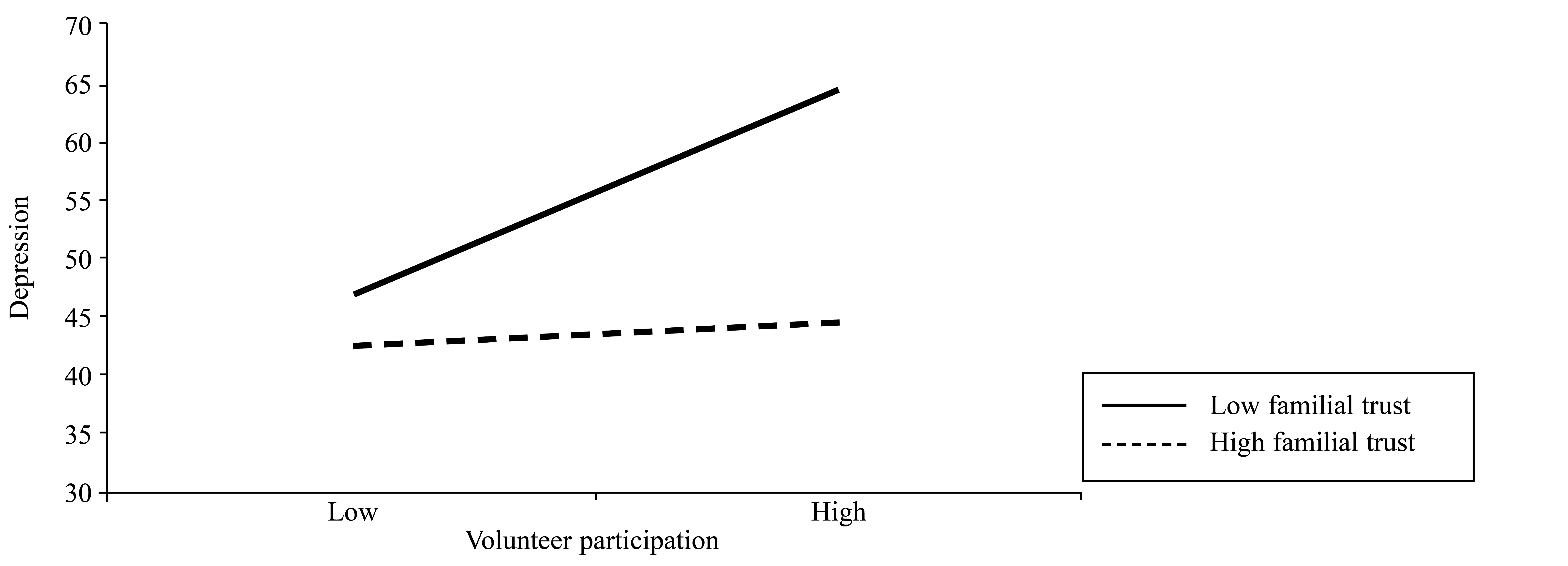

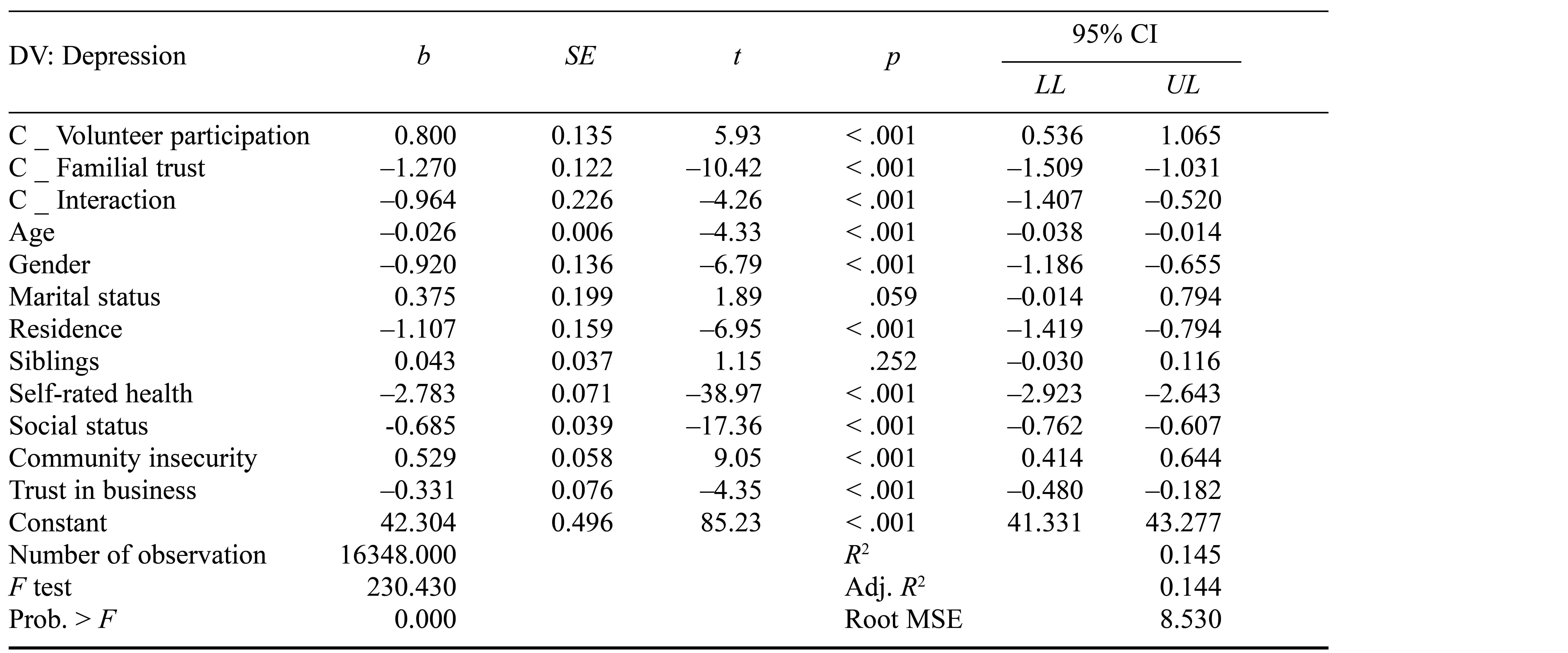

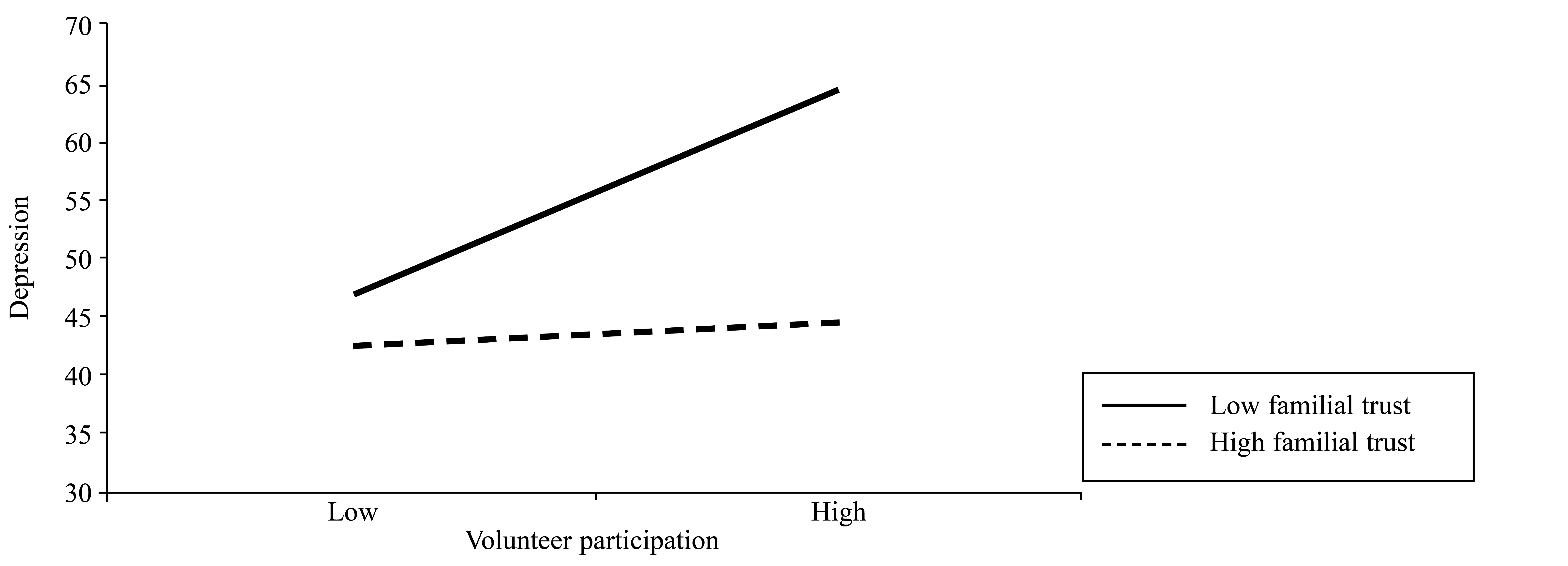

The moderation analysis detailed in Table 4 elucidates the nuanced dynamics between volunteer participation and depression, with familial trust functioning as a significant moderating factor (see Figure 1). The coefficients are presented in their standardized form, which is particularly beneficial in models incorporating interaction terms, such as those assessing moderating effects. The interaction term between volunteer participation and familial trust presented a negative coefficient, evidencing that heightened familial trust corresponded with a mitigated depressive impact resulting from volunteer participation. These findings supported Hypothesis 2.

Table 4. Moderation Effect Results

Note. DV = dependent variable; CI = confidence interval; C = centralization; Interaction = volunteer participation × familial trust. Coefficients are presented in their standardized form, which is particularly beneficial in models incorporating interaction terms, such as those assessing moderating effects. Standardization clarifies the influence of these interactions by illustrating how each standard deviation change in the variables impacts the dependent variable. This approach ensures that the effects of different predictors are comparable on a consistent scale.

Figure 1. Simple Slopes Analysis

Note. Familial trust attenuated the link between volunteer participation and depression within nascent social organizational structures.

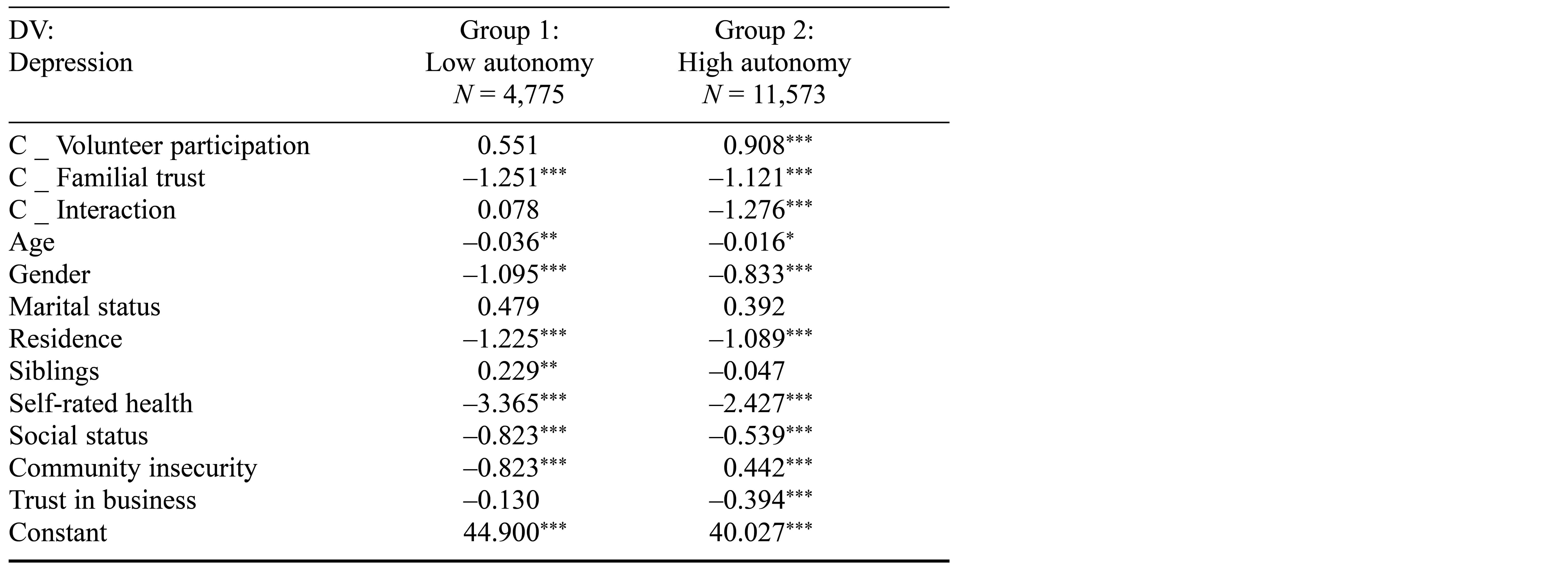

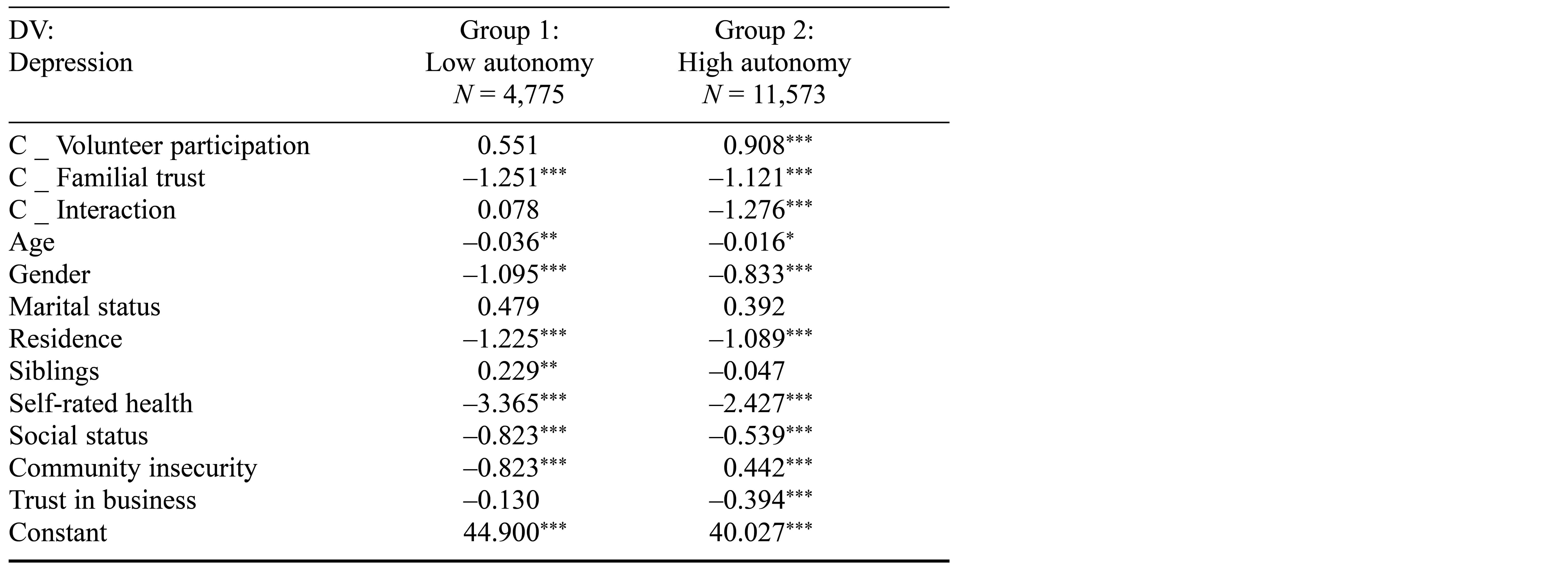

Heterogeneity Based on Autonomy

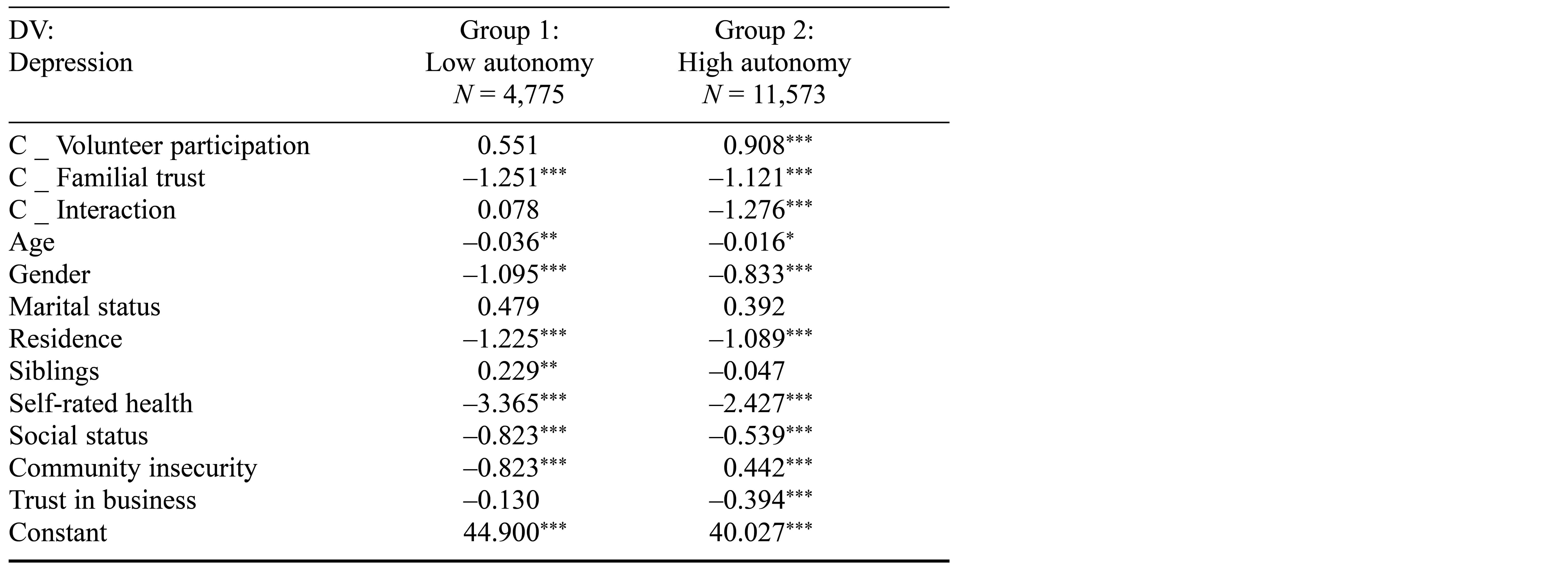

The heterogeneity analysis presented in Table 5 delineates a dichotomy based on levels of autonomy among participants. The coefficients are presented in their standardized form; for individuals characterized by lower autonomy, familial trust did not play a statistically significant moderating role. In stark contrast, within the subset characterized by high autonomy, this study revealed a significant main effect, with the coefficient indicating a correlation of 0.908 (p < .001) between volunteer participation and depression. Moreover, in this group with elevated levels of autonomy, the moderating influence of familial trust significantly buffered the positive correlation between volunteer participation and depression outcomes, as denoted by a coefficient of −1.276 (p < .001). Nevertheless, it is paramount to recognize that the protective mechanism afforded by familial trust was absent within the cohort exhibiting low autonomy, wherein a discernible main effect of volunteer participation on depression failed to materialize, positing that the salutary effects of volunteer endeavors on mental health are inherently conditional upon the degree of individual autonomy, thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

Table 5. Heterogeneity Test Results

Note. DV = dependent variable; C = centralization; Interaction = volunteer participation × familial trust. Coefficients are presented in their standardized form, which is particularly beneficial in models incorporating interaction terms, such as those assessing heterogeneity. Standardization clarifies the influence of these interactions by illustrating how each standard deviation change in the variables impacts the dependent variable. This approach ensures that the effects of different predictors are comparable on a consistent scale. Autonomy levels were determined by a median split of the autonomy scale, which ranges from 1 (low) to 10 (high). Scores above the median were classified as high autonomy; those below were categorized as low autonomy.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Robustness Analysis

To ensure the robustness of the model, I employed two distinct approaches. First, I introduced a critical omitted variable: the sense of fairness. Participants evaluated whether their current standard of living was fair relative to their efforts at work, with options ranging from 1 (completely unfair) to 5 (completely fair). This sense of fairness was incorporated into the original model. Second, I conducted a subgroup analysis. The study focused on adolescents who often engage in volunteer activities due to school mandates; adolescents are defined as individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 years (World Health Organization, 2023). Both approaches yielded results consistent with the initial model, affirming the robustness of the study’s findings.

Discussion

The findings inject a novel dimension into the discourse on volunteerism and mental health, particularly in the context of China’s evolving social landscape. The revelation that volunteer participation may exacerbate depressive symptoms challenges the prevailing narrative within the Western-centric research paradigm, which predominantly posits volunteerism as a conduit for enhanced mental well-being (J. Yang, 2017). This departure suggests that the impact of volunteerism is not universally positive but is instead mediated by specific cultural and social factors unique to certain contexts.

Diverging from earlier findings by Chan et al. (2021), Y. Liu et al. (2020), Wu et al. (2023), and H.-L. Yang et al. (2022), this study has revealed a positive association between volunteer participation and depression, challenging the previously assumed negative correlation. Prior research (Jiang, 2022; Wu et al., 2023) mainly focused on older adults, possibly overlooking the complex challenges the broader Chinese population faces. Particularly since 2019, the deceleration of China’s economic growth has intensified the phenomenon of social involution (A. Y. Liu et al., 2022). With the economic deceleration, budget cuts could reduce financial support for community social organizations, diminishing their capacity to engage volunteers (T. Liu et al., 2021), which may, in turn, lessen the beneficial effects of volunteering on mental health. This has escalated societal pressures and anxiety, contributing to an overall increase in stress levels within the community (Yuan, 2022). Additionally, by focusing predominantly on older adults, earlier studies (e.g., Jiang, 2022; Wu et al., 2023) may have overlooked the distinct experiences and needs of other age demographics during this time. Young and middle-aged individuals, grappling with job stress, familial duties, and societal shifts, may exhibit mental health needs and responses to volunteer work that are markedly different from those of older populations (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Both Jiang (2022) and Miao et al. (2021) observed that there has been an increase in formal volunteer services at the community level in China since 2019. This surge was anticipated to broaden the avenues for social engagement, thereby enhancing life satisfaction and well-being, especially for individuals aiming to boost their self-esteem and belongingness through altruistic acts (Piliavin & Siegl, 2007). However, this increase in community-level formal volunteer services may also introduce challenges, particularly concerning the essence and quality of volunteer work. The expansion in volunteer initiatives could lead to organizational and managerial issues, such as mismatches between volunteers and their tasks (Omoto & Snyder, 2002), a lack of adequate training and support (Hu, 2021), and insufficient acknowledgment of volunteers’ efforts (Lu & Gilmour, 2004). These issues may undermine the volunteering experience and foster feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction, adversely affecting mental health (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Moreover, the proliferation of formal volunteer services might amplify the pressure to participate. In specific sociocultural settings, the societal expectation of partaking in volunteering, especially when framed as a civic responsibility by the community (Oyserman & Lee, 2008), could make volunteering feel obligatory, adding stress, particularly for those already juggling work and familial responsibilities (Triandis, 2001). This added strain from volunteering could intensify psychological stress, impacting mental well-being.

My findings underscore the pivotal role of familial trust in moderating the relationship between volunteerism and depression. This aligns with recent research emphasizing the importance of family dynamics in mental health outcomes within family-centric cultures (Cheng et al., 2017). My results suggest that in societies where familial ties are integral to personal identity and social functioning, as is the case in China, the presence of strong familial trust can serve as a buffer against the negative psychological impacts of volunteer activities, especially when these activities are misaligned with personal or cultural values.

Furthermore, this study brings to the forefront the critical role of individual autonomy in this complex interplay. Autonomy is posited not just as a personal attribute but as a culturally informed construct that shapes how volunteer activities are perceived and experienced (Maas et al., 2019). In settings where autonomy is encouraged and fostered, familial trust can be leveraged more effectively to mitigate the potential adverse effects of volunteerism on mental health. This insight extends the conversation around volunteerism from a simplistic binary of beneficial versus detrimental to a more nuanced understanding that considers the interplay of autonomy and familial dynamics.

Finally, the introduction of a psychological growth model that integrates public engagement with familial culture represents a significant theoretical contribution to the field. This model suggests that the pathway to effective and mentally enriching volunteerism lies not solely in the act of volunteering itself but in how it is embedded within the individual’s familial and cultural context (Chirkov et al., 2003).

From a policy perspective, these findings have profound implications. They suggest that mental health interventions and volunteer programs in China should not merely replicate Western models but need to be intricately woven into the fabric of Chinese familial and cultural values (Jiang, 2022). Policies should promote volunteerism that respects and integrates family dynamics and individual autonomy, recognizing these as vital components in the pursuit of mental health and societal well-being. In sum, this study illuminates the multifaceted nature of volunteerism’s impact on mental health, particularly within the unique sociocultural context of China, and calls for a culturally sensitive approach to fostering public engagement and psychological well-being.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has limitations, particularly the need for experimental designs to further validate the findings. Such future research could offer more definitive insights into the causal relationships between the examined variables. Moreover, while I accounted for a variety of covariates in the analysis, the potential confounding variable of employment status was not adjusted for due to constraints in the survey data. Even though individuals who participate in volunteering activities at a high frequency represent a very small proportion in this study, future research could investigate the relationship between frequent volunteering (e.g., daily participation) and full-time employment status, exploring whether more active volunteers are less likely to be engaged in full-time jobs. Furthermore, it is crucial to assess whether this group of individuals has a higher susceptibility to depression, thereby enhancing understanding of the broader implications of volunteering frequency for mental health and employment.

Conclusion

This study has elucidated the paradoxical influence of volunteer participation on depression, challenging the prevailing orthodoxy and underscoring the salience of familial trust and individual autonomy in mitigating such effects. This revelation signals a doctrinal shift, suggesting that the integration of private and public domains can be mediated by the familial construct, thus fostering an innovative pathway for the resolution of personal internal conflicts. By reconceptualizing the nexus between volunteer engagement and psychological well-being, this study advocates for a restructured paradigm where familial dynamics are instrumental in bridging the gap between individual experiences and broader societal engagement.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924–973.

Borgonovi, F. (2008). Doing well by doing good. The relationship between formal volunteering and self-reported health and happiness. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11), 2321–2334.

Califf, R. M., Wong, C., Doraiswamy, P. M., Hong, D. S., Miller, D. P., Mega, J. L., & Baseline Study Group. (2022). Importance of social determinants in screening for depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(11), 2736–2743.

Chan, W., Chui, C. H. K., Cheung, J. C. S., Lum, T. Y. S., & Lu, S. (2021). Associations between volunteering and mental health during COVID-19 among Chinese older adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(6), 599–612.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., ... Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236.

Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. The Asia–Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 377–387.

Cheng, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, F., Zhang, P., Ye, B., & Liang, Y. (2017). The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China’s transition: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Family Practice, 18, Article 59.

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 97–110.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Grönlund, H. (2011). Identity and volunteering intertwined: Reflections on the values of young adults. VOLUNTAS, 22(4), 852–874.

Haivas, S., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2012). Self-determination theory as a framework for exploring the impact of the organizational context on volunteer motivation: A study of Romanian volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 1195–1214.

Hammack, P. L. (2018). Social psychology and social justice: Critical principles and perspectives for the twenty-first century. In P. L. Hammack (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social psychology and social justice (pp. 3–39). Oxford University Press.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Hu, M. (2021). Making the state’s volunteers in contemporary China. VOLUNTAS, 32(6), 1375–1388.

Hu, M., Zhang, Q., & Sidel, M. (2023). Building state-controlled volunteering in China. The China Quarterly, 256, 854–870.

Janoski, T., & Wilson, J. (1995). Pathways to voluntarism: Family socialization and status transmission models. Social Forces, 74(1), 271–292.

Jiang, N. (2022). Formal volunteering and depressive symptoms among community‐dwelling older adults in China: A longitudinal cross‐level analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e5673–e5684.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78, 458–467.

Kurzban, R., & Leary, M. R. (2001). Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 187–208.

Liu, A. Y., Oi, J. C., & Zhang, Y. (2022). China’s local government debt: The grand bargain. The China Journal, 87(1), 40–71.

Liu, L. (2008). Filial piety, guanxi, loyalty, and money. In I. Marková & A. Gillespie (Eds.), Trust and distrust: Sociocultural perspectives (pp. 51–78). Information Age Publishing Inc.

Liu, T., Wang, Y., Li, H., & Qi, Y. (2021). China’s low-carbon governance at community level: A case study in Min’an community, Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 311, Article 127530.

Liu, Y., Duan, Y., & Xu, L. (2020). Volunteer service and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults: The mediating role of health. Social Science & Medicine, 265, Article 113535.

Lowe, G., Willis, G., & Gibson, K. (2019). You do what? A qualitative investigation into the motivation to volunteer with circles of support and accountability. Sexual Abuse, 31(2), 237–260.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 269–291.

Maas, J., van Assen, M. A. L. M., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., Rutten, E. A. P., & Bekker, M. H. J. (2019). Autonomy–connectedness, self-construal, and acculturation: Associations with mental health in a multicultural society. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(1), 80–99.

Martela, F., Lehmus-Sun, A., Parker, P. D., Pessi, A. B., & Ryan, R. M. (2023). Needs and well-being across Europe: Basic psychological needs are closely connected with well-being, meaning, and symptoms of depression in 27 European countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(5), 501–514.

Matsuba, M. K., Hart, D., & Atkins, R. (2007). Psychological and social-structural influences on commitment to volunteering. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 889–907.

Miao, Q., Schwarz, S., & Schwarz, G. (2021). Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Development, 137, Article 105128.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2003). Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Social Science & Medicine, 56(2), 259–269.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846–867.

Oyserman, D., & Lee, S. W. S. (2008). Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 311–342.

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., Joseph, H. J., & Henderson, C. A. (1996). Conceptualizing and assessing social support in the context of the family. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family (pp. 3–23). Plenum Press.

Piliavin, J. A., & Siegl, E. (2007). Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(4), 450–464.

Post, S. G. (2005). Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. In G. Ironson & L. H. Powell (Eds.), An exploration of the health benefits of factors that help us to thrive: A special issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 66–76). Psychology Press.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Schwartz, S. H., Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2010). Basic personal values, core political values, and voting: A longitudinal analysis. Political Psychology, 31(3), 421–452.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 115–131.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism‐collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924.

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press.

Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1–18.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240.

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates.

World Health Organization. (2023). Adolescent health.

Wu, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Leeson, G. W., Chen, G., ... Yue, X. G. (2023). Volunteering and depression among older adults: An empirical analysis based on CLASS 2018. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(3), 403–419.

Wuthnow, R. (2012). Acts of compassion: Caring for others and helping ourselves. Princeton University Press.

Yan, Y. (2016). Intergenerational intimacy and descending familism in rural north China. American Anthropologist, 118(2), 244–257.

Yang, H.-L., Zhang, S., Zhang, W.-C., Shen, Z., Wang, J.-H., Cheng, S.-M., … Li, Z.-Y. (2022). Volunteer service and well-being of older people in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, Article 777178.

Yang, J. (2017). Mental health in China: Change, tradition, and therapeutic governance. John Wiley & Sons.

Yang, L. H., & Kleinman, A. (2008). ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 398–408.

Yuan, S. (2022). Silent resistance against social pressures in China. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6(1), 11–12.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924–973.

Borgonovi, F. (2008). Doing well by doing good. The relationship between formal volunteering and self-reported health and happiness. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11), 2321–2334.

Califf, R. M., Wong, C., Doraiswamy, P. M., Hong, D. S., Miller, D. P., Mega, J. L., & Baseline Study Group. (2022). Importance of social determinants in screening for depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(11), 2736–2743.

Chan, W., Chui, C. H. K., Cheung, J. C. S., Lum, T. Y. S., & Lu, S. (2021). Associations between volunteering and mental health during COVID-19 among Chinese older adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(6), 599–612.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., ... Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 216–236.

Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. The Asia–Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 377–387.

Cheng, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, F., Zhang, P., Ye, B., & Liang, Y. (2017). The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China’s transition: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Family Practice, 18, Article 59.

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 97–110.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Grönlund, H. (2011). Identity and volunteering intertwined: Reflections on the values of young adults. VOLUNTAS, 22(4), 852–874.

Haivas, S., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2012). Self-determination theory as a framework for exploring the impact of the organizational context on volunteer motivation: A study of Romanian volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 1195–1214.

Hammack, P. L. (2018). Social psychology and social justice: Critical principles and perspectives for the twenty-first century. In P. L. Hammack (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social psychology and social justice (pp. 3–39). Oxford University Press.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Hu, M. (2021). Making the state’s volunteers in contemporary China. VOLUNTAS, 32(6), 1375–1388.

Hu, M., Zhang, Q., & Sidel, M. (2023). Building state-controlled volunteering in China. The China Quarterly, 256, 854–870.

Janoski, T., & Wilson, J. (1995). Pathways to voluntarism: Family socialization and status transmission models. Social Forces, 74(1), 271–292.

Jiang, N. (2022). Formal volunteering and depressive symptoms among community‐dwelling older adults in China: A longitudinal cross‐level analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e5673–e5684.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78, 458–467.

Kurzban, R., & Leary, M. R. (2001). Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 187–208.

Liu, A. Y., Oi, J. C., & Zhang, Y. (2022). China’s local government debt: The grand bargain. The China Journal, 87(1), 40–71.

Liu, L. (2008). Filial piety, guanxi, loyalty, and money. In I. Marková & A. Gillespie (Eds.), Trust and distrust: Sociocultural perspectives (pp. 51–78). Information Age Publishing Inc.

Liu, T., Wang, Y., Li, H., & Qi, Y. (2021). China’s low-carbon governance at community level: A case study in Min’an community, Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 311, Article 127530.

Liu, Y., Duan, Y., & Xu, L. (2020). Volunteer service and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults: The mediating role of health. Social Science & Medicine, 265, Article 113535.

Lowe, G., Willis, G., & Gibson, K. (2019). You do what? A qualitative investigation into the motivation to volunteer with circles of support and accountability. Sexual Abuse, 31(2), 237–260.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 269–291.

Maas, J., van Assen, M. A. L. M., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., Rutten, E. A. P., & Bekker, M. H. J. (2019). Autonomy–connectedness, self-construal, and acculturation: Associations with mental health in a multicultural society. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(1), 80–99.

Martela, F., Lehmus-Sun, A., Parker, P. D., Pessi, A. B., & Ryan, R. M. (2023). Needs and well-being across Europe: Basic psychological needs are closely connected with well-being, meaning, and symptoms of depression in 27 European countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(5), 501–514.

Matsuba, M. K., Hart, D., & Atkins, R. (2007). Psychological and social-structural influences on commitment to volunteering. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 889–907.

Miao, Q., Schwarz, S., & Schwarz, G. (2021). Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Development, 137, Article 105128.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2003). Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Social Science & Medicine, 56(2), 259–269.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846–867.

Oyserman, D., & Lee, S. W. S. (2008). Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 311–342.

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., Joseph, H. J., & Henderson, C. A. (1996). Conceptualizing and assessing social support in the context of the family. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family (pp. 3–23). Plenum Press.

Piliavin, J. A., & Siegl, E. (2007). Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(4), 450–464.

Post, S. G. (2005). Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. In G. Ironson & L. H. Powell (Eds.), An exploration of the health benefits of factors that help us to thrive: A special issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 66–76). Psychology Press.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Schwartz, S. H., Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2010). Basic personal values, core political values, and voting: A longitudinal analysis. Political Psychology, 31(3), 421–452.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 115–131.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism‐collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924.

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press.

Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1–18.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240.

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates.

World Health Organization. (2023). Adolescent health.

Wu, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Leeson, G. W., Chen, G., ... Yue, X. G. (2023). Volunteering and depression among older adults: An empirical analysis based on CLASS 2018. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(3), 403–419.

Wuthnow, R. (2012). Acts of compassion: Caring for others and helping ourselves. Princeton University Press.

Yan, Y. (2016). Intergenerational intimacy and descending familism in rural north China. American Anthropologist, 118(2), 244–257.

Yang, H.-L., Zhang, S., Zhang, W.-C., Shen, Z., Wang, J.-H., Cheng, S.-M., … Li, Z.-Y. (2022). Volunteer service and well-being of older people in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, Article 777178.

Yang, J. (2017). Mental health in China: Change, tradition, and therapeutic governance. John Wiley & Sons.

Yang, L. H., & Kleinman, A. (2008). ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 398–408.

Yuan, S. (2022). Silent resistance against social pressures in China. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6(1), 11–12.