Compared with families where there is little or no cohesion, a cohesive family may function better as a team, which facilitates better engagement in important disease-care tasks (Björnberg & Nicholson, 2007; Jaskiewicz et al., 2017). Furthermore, the health status of each individual is part of the health environment of the community, which involves and affects the safety and health of everybody in that community, and also directly affects the social environment. Abiding by the social order, respecting public interests, and caring for the interests of others are the basic moral qualities and the concrete embodiment of the social ethics required of each member of society (Q. Zhou, 2020). Considering the family as the smallest unit of prevention and control, preventive measures at home can maximize the effect of isolation and reduce viral transmission during a pandemic. In COVID-19 pandemic prevention, all family members form a team, and the behavior of each member affects the performance of the whole team. The performance of pandemic prevention at home is not a traditional family task or family relationship performance, but a shared responsibility based on the goal of infection prevention.

Pandemic prevention and control are related to the health of every member of the family team. Research into team performance thus far has mostly been aimed at enterprises, companies, schools, and other units, and has rarely been undertaken in the family group context. In a broad sense, team performance refers to the degree to which team members carry out and achieve predetermined goals effectively, and it is mainly composed of three parts: the achievement of team goals, the satisfaction of team members, and the ability of the team members to cooperate (Hackman & Wageman, 2005). The factors influencing team performance include individual factors, such as sense of responsibility, sense of efficacy, and decision making, and environmental factors, including leadership style and team atmosphere (Jackson et al., 2003; LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). As important members of the family, nearly 40 million college students in China form an active and energetic force in society and shoulder the burden of national revitalization (Xi, 2019). Universities are the halls of science and have special resources in promoting the rational spirit of seeking truth from facts; being pragmatic, pioneering, and innovative; advancing health concepts; and offering psychological intervention and counselling. University students are extremely important volunteer resources and incubators of various volunteer or public welfare organizations that can play an important role in social mobilization and guidance in pandemic prevention and control (Hong, 2020). In the new era in China that began in 2012, college students now face more profound social changes, more diversified lives, and greater challenges compared with their parents, and pay more attention to environmental protection. The diversification, internationalization, and networking of media inevitably make these individuals more modern, heterogeneous, and open in terms of their social consciousness compared with their parents (Li & Li, 2008). Therefore, college students have a unique position regarding dissemination of information on government policy, and popularization of knowledge about pandemic prevention and control. Whether students can assume the responsibility of publicizing, popularizing, and implementing pandemic prevention policy directly affects pandemic prevention at home. Therefore, it is of theoretical value and practical significance to estimate the influence of the mechanism of college students’ sense of responsibility for prevention of COVID-19 at home, to clarify their responsibility as young people in the new era, to encourage them to be proactive in offering suggestions to their family, and to strengthen the social contribution of the family as a problem-solving unit.

Sense of responsibility refers to consciously assuming obligations and authority, and the tendency of individuals to be active in engaging with the environment when taking part in social events and exchanges (Sun, 2006). College students’ sense of responsibility in this study refers to the realization of their preventative duty in the context of the family during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their consciousness and behavioral disposition while considering prevention of transfer of infection as their duty within the family (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Employees with a strong sense of responsibility are highly internally motivated to benefit their organization (Zhu & Akhtar, 2019), and are inclined to engage in constructive behaviors conducive to improving organizational efficiency (Fuller et al., 2006). Responsibility may affect task performance through its influence on task habits (Motowildo et al., 1997). College students with a stronger sense of responsibility show more outstanding academic achievement, altruistic behavior, and team performance (Huang et al., 2016; Such & Walker, 2004). Therefore, we formed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: College students’ sense of responsibility will have a positive effect on the prediction of their pandemic prevention behavior in their family home.

Voice behavior is a kind of positive, challenging, and encouraging active behavior, including transformative communication to change the status quo. Voice behavior may change the current environment of employees and disrupt the relationship between employees and colleagues. However, in the long run, voice behavior is constructive and of positive significance to the development of the organization (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001; Stamper & Van Dyne, 2001). Voice behavior is a changeable and constructive interpersonal communication behavior aimed at improving the organizational environment (Motowildo et al., 1997). In these definitions the form of voice behavior is pointed out, and its challenging and transformative nature is emphasized. Voice behavior may challenge the status quo or embarrass superiors (Detert & Burris, 2007). In the Chinese context, previous researchers proposed a definition of promotive voice that entails actively proposing new ideas and suggestions to promote an organization’s production and operation (Liang & Farh, 2008). In this study we defined promotive voice as college students actively proposing new ideas and suggestions that can affect pandemic prevention in their family home. Numerous studies have reported finding that promotive voice behavior can help organizations or teams to optimize processes (Gollan & Wilkinson, 2007; Janssen & Gao, 2015; J. Zhou & George, 2001). Ultimately, promotive voice improves organizational and team effectiveness (Gollan & Wilkinson, 2007; Hackman & Wageman, 2005; Hung et al., 2012). Additionally, individuals with a strong sense of responsibility are more likely than are those who have a weaker sense of responsibility to engage in promotive voice and innovative behaviors that are beneficial to team development. For example, Hackman and Wageman (2005) reported that individual responsibility is significantly correlated with promotive voice behavior and the correlation is more strongly significant than that for the correlation between voice behavior and task performance. Employees who feel a sense of responsibility to the organization exhibit voice behavior more often than those do who not feel this responsibility (Fuller et al., 2006; LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). Young, well-educated people exhibit more voice behavior than do either older people or those who have a low level of education (Farrell, 1983). On the basis of the above analysis, we formed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Promotive voice will play a mediating role between college students’ sense of responsibility and their performance in relation to pandemic prevention in their family home.

Cohesion refers to the centripetal force that can unite team members as a whole; it comprises all the group’s knowledge, ability, and strength. Family cognitive cohesion emphasizes the consistency of values among family members, recognizing vision and goals, and the degree of close mutual connection and joint efforts (Björnberg & Nicholson, 2007). In families where members have high cognitive cohesion comprising common beliefs, values, and attitudes toward people, this can promote the improvement of family atmosphere, produce positive effects, make members strive to achieve a balance between work and family, and, thus, effectively promote family members’ motivation to contribute to the family (Z. Chen et al., 2017). The formation of team cohesion can enhance the sense of trust among team members, improve interpersonal relationships, and strengthen cooperation, thereby improving organizational performance (Van Woerkom & Sanders, 2010). Therefore, interpersonal trust and cohesion are conducive to conflict resolution and, thus, improve performance (Deng & Ding, 2012). Cognitive cohesion based on value identification can enhance the sense of responsibility among team members, uniting them further (R. Zhou, 2004). That is, a sense of responsibility can further promote the enhancement of cohesion. Some studies have found that team responsibility can promote team knowledge collaboration. Xu and Li (2019) reported a highly positive correlation between open communication and cognitive cohesion, and Björnberg and Nicholson (2007) found that cognitive cohesion is positively correlated with overall family health. The aforementioned research showed that sense of responsibility directly affects cognitive cohesion and performance, and improves team performance by promoting knowledge sharing or value identification. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Cognitive cohesion in the family will play a mediating role between college students’ sense of responsibility and their pandemic prevention performance in the family home.

Hypothesis 4: Promotive voice behavior and cognitive cohesion in the family will exert chain mediation effects on the relationship between college students’ sense of responsibility and their pandemic prevention performance in the family home.

Method

Participants

According to the higher prevalence of COVID-19 in these areas compared with other parts of China, we chose approximately 1,000 college students from 10 universities in Hubei, Hunan, Zhejiang, Henan, and Anhui to participate in this study. Teachers at these institutions distributed the survey in their classes. We received back 1,323 copies of the completed survey and excluded 267 from respondents whose place of residence was not within the target provinces. Thus, there were 1,056 valid surveys and the effective return rate was 79.8%. The sample comprised 166 men and 890 women, and the place of residence of 201 of the students was Hubei Province, 417 lived in Hunan, 125 in Zhejiang, 167 in Henan, and 146 in Anhui. Within these provinces, the students came from 194 cities, 220 counties, 189 townships, and 453 villages.

Measures

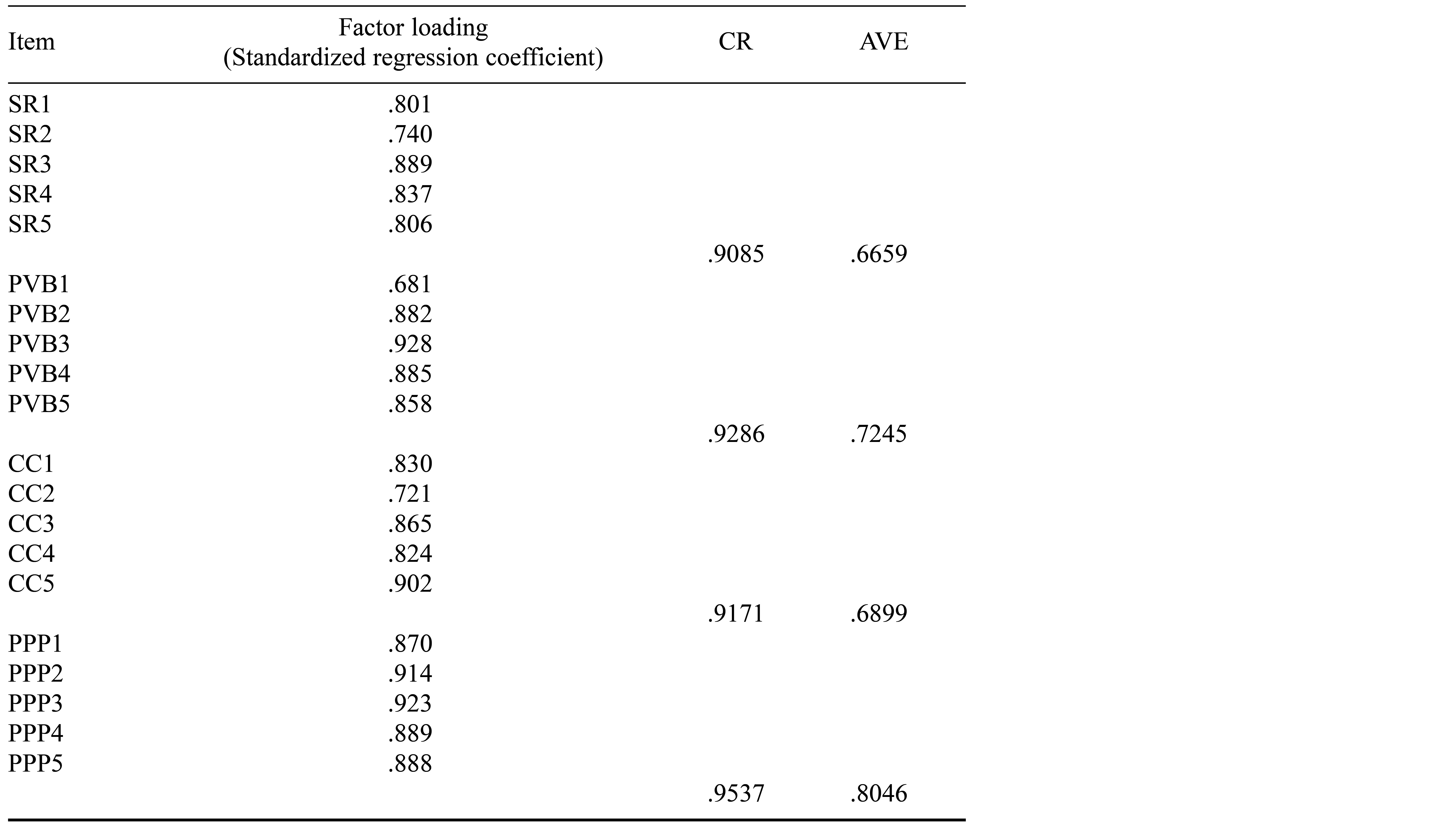

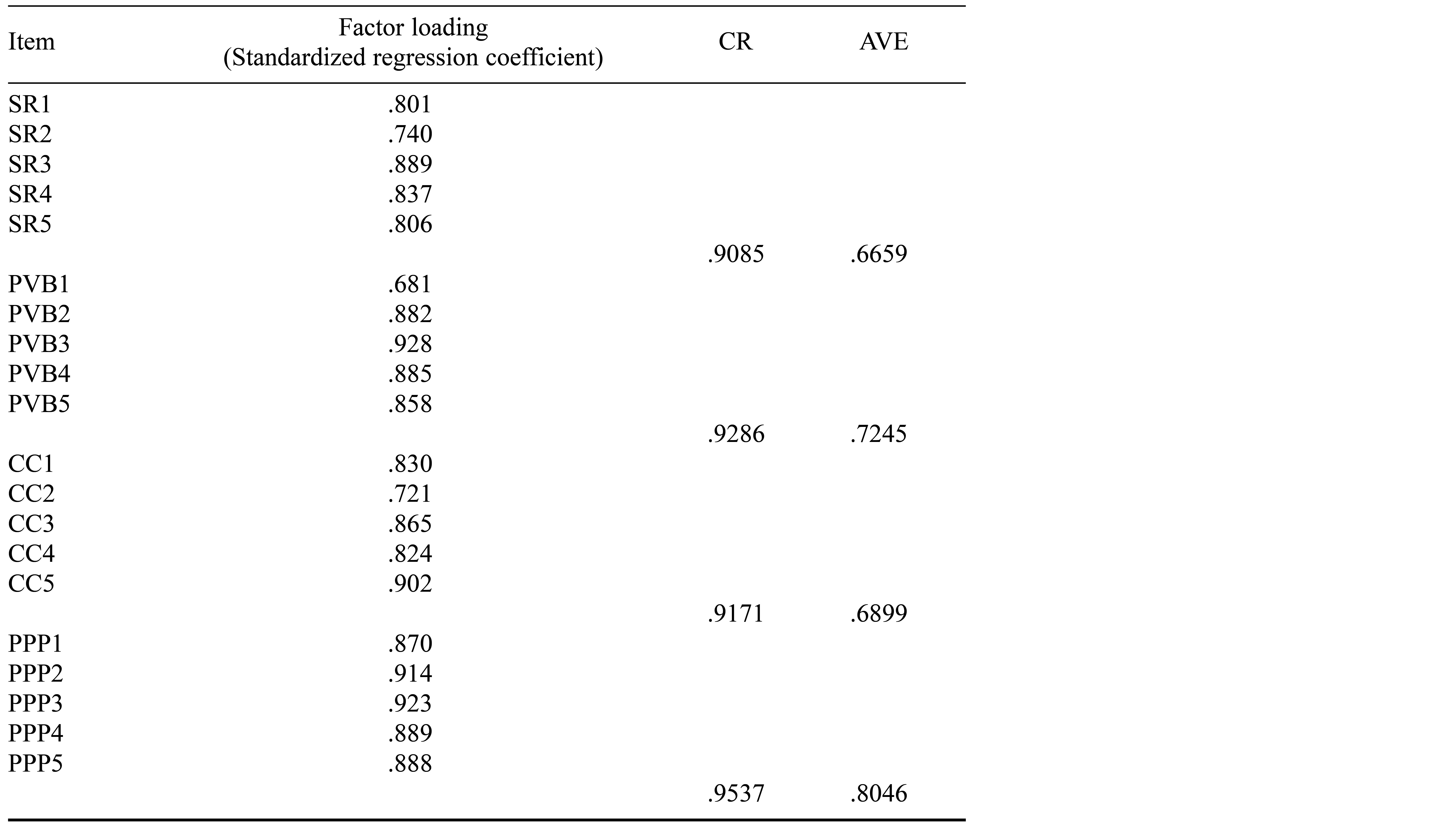

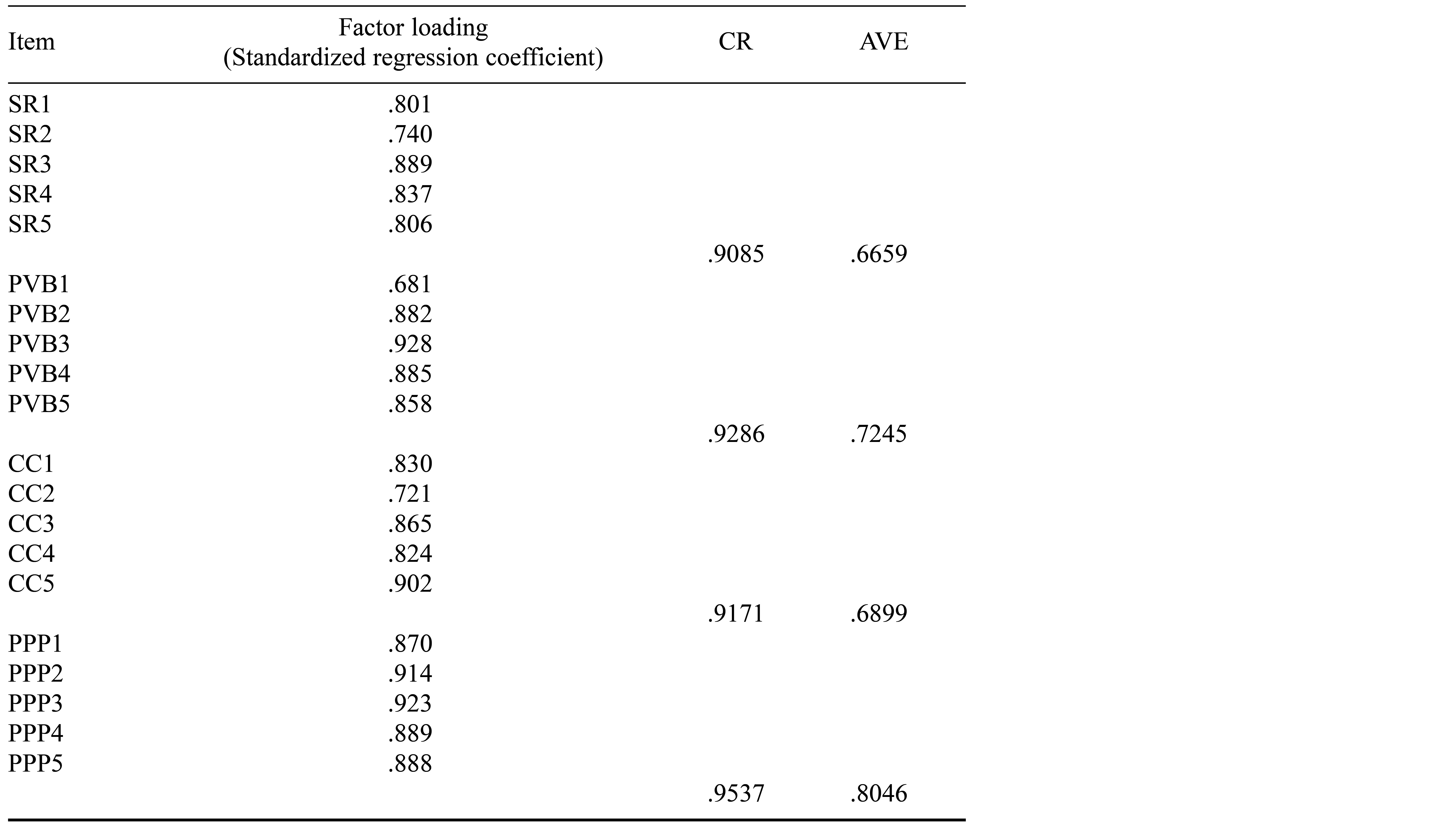

Responses were made on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The reliability and factor loading statistics were satisfactory across all scales (see Tables 1 and 2). Items in each measure were adapted from the original versions to fit the specific context of the pandemic.

Sense of Responsibility

Morrison and Phelps (1999) compiled the Sense of Responsibility Scale, which was translated into Chinese by Shi (2013). The scale has five items, which we adapted to read “I am responsible for bringing new changes to pandemic prevention work,” “I have the responsibility to improve my home quarantine environment,” “I have the obligation to improve the methods and procedures of pandemic prevention,” “I have the responsibility to point out or correct problems in pandemic prevention,” and “I have the responsibility to challenge or change my position in pandemic prevention work.” In this study Cronbach’s reliability was .91.

Promotive Voice Behavior

Liang et al. (2012) compiled the Promotive Voice Behavior Scale, which has five items: “I actively propose new measures that will benefit my family,” “I actively propose to improve pandemic prevention procedures,” “I take the initiative to put forward reasonable suggestions to achieve pandemic prevention goals,” “I have put forward constructive suggestions that can improve the quality of pandemic control implementation,” and “I will take the initiative to think about possible problems in pandemic prevention and put forward my own suggestions.” In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Cognitive Cohesion

Björnberg and Nicholson (2007) compiled the five-item Cognitive Cohesion subscale as part of the Family Climate Scales. The scale was translated into Chinese by Z. Chen et al. (2017). The items are “In my family, we have similar opinions on most of the pandemic prevention efforts,” “In my family, we have shared interests and tastes during the pandemic,” “In my family, we have very similar attitudes and beliefs about pandemic prevention,” “In my family, we have few extremely different views on pandemic prevention,” and “In my family, we share similar values when it comes to pandemic prevention.” In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Pandemic Prevention Performance at Home

The measure of pandemic prevention performance at home was adapted from the scale developed by Van Der Vegt and Bunderson (2005) and translated into Chinese by W. Chen et al. (2019). The five items describe the aspects of efficiency, quality, overall achievement, productivity, and mission fulfillment. Many Chinese scholars have adapted and used this scale. The items are “In general, my family members are satisfied with our home pandemic prevention work” (overall achievement), “My family members have a strong sense of responsibility for home pandemic prevention” (quality), “My family members are very involved in the goals of home vaccination” (efficiency), “Current ways of working can inspire us to continue to improve the effectiveness of home vaccination” (productivity), and “All in all, my family members are highly satisfied with the operation of the whole home pandemic prevention” (mission fulfillment). In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .95.

Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Study Variables

Note. SR = sense of responsibility; PVB = promotive voice behavior; CC = family cognitive cohesion; PPP = pandemic prevention performance at home; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted. All standardized factor loadings were significant at p < .001.

Results

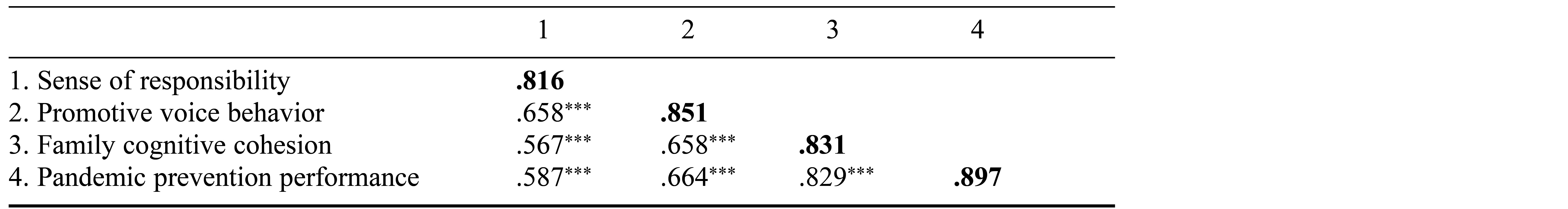

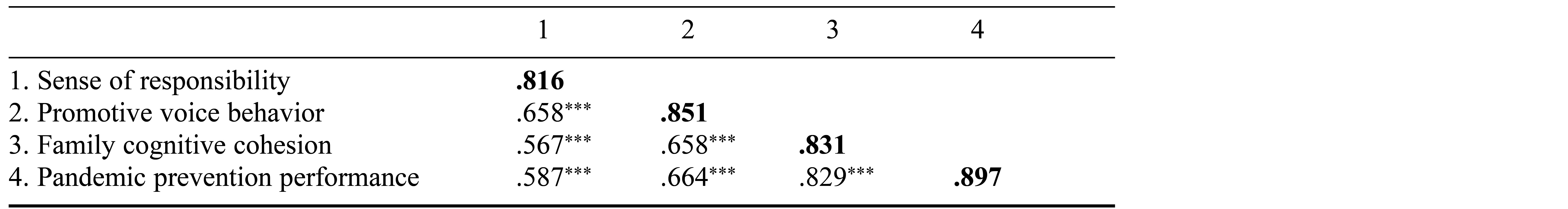

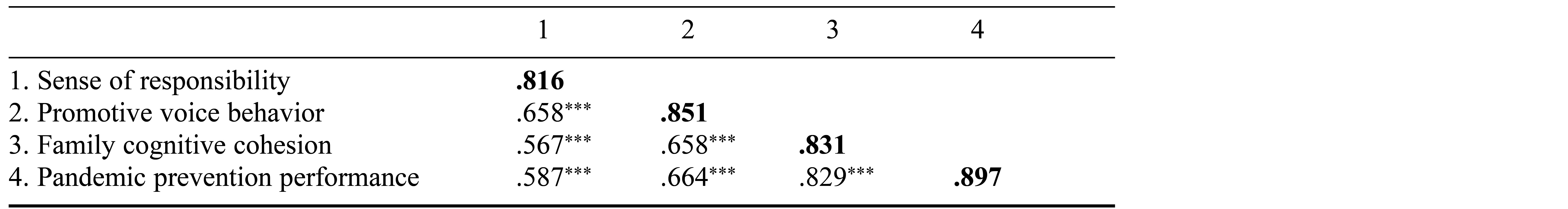

College students’ sense of responsibility was significantly and positively correlated with promotive voice behavior, family cognitive cohesion, and pandemic prevention performance (see Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation Coefficients and Square Roots of Average Variance Extracted for Study Variables

Note. Square roots of average variance extracted are shown in boldface on the diagonal.

*** p < .001.

Chain Mediation Effects Analysis

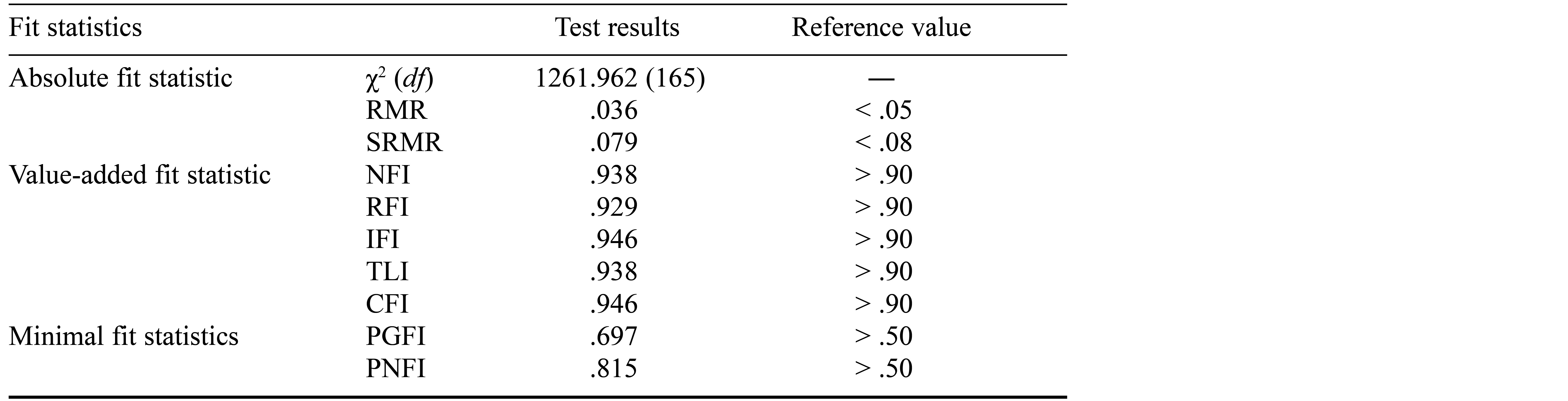

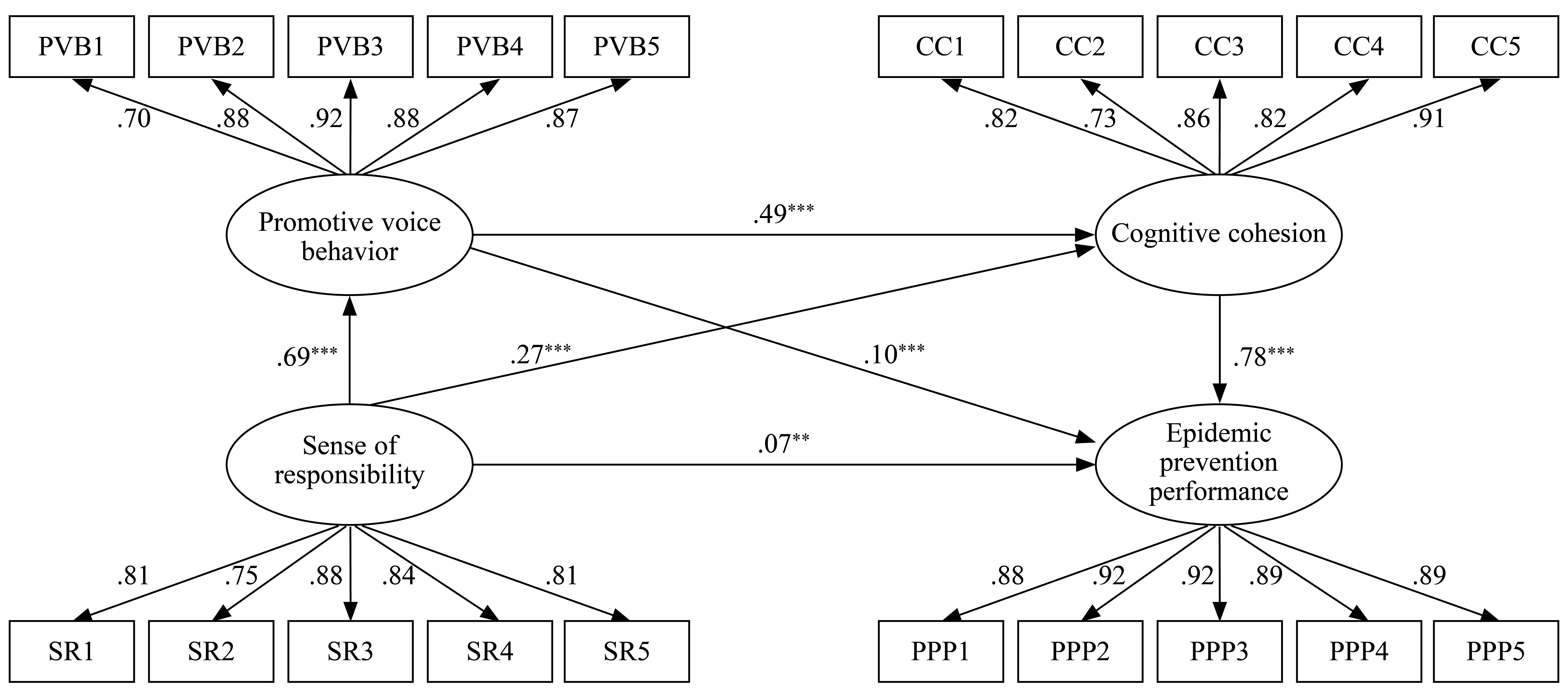

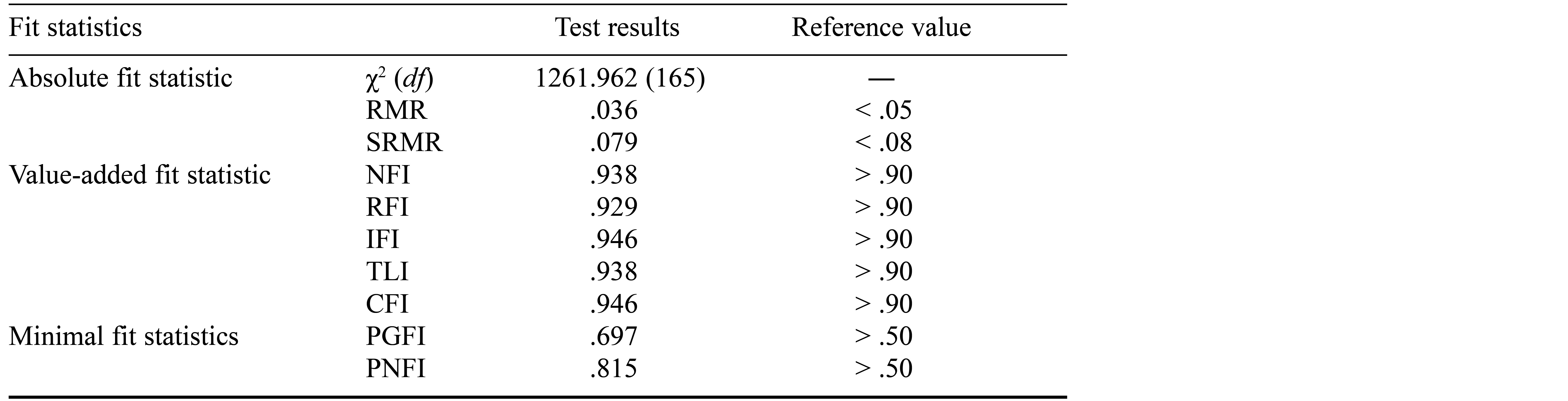

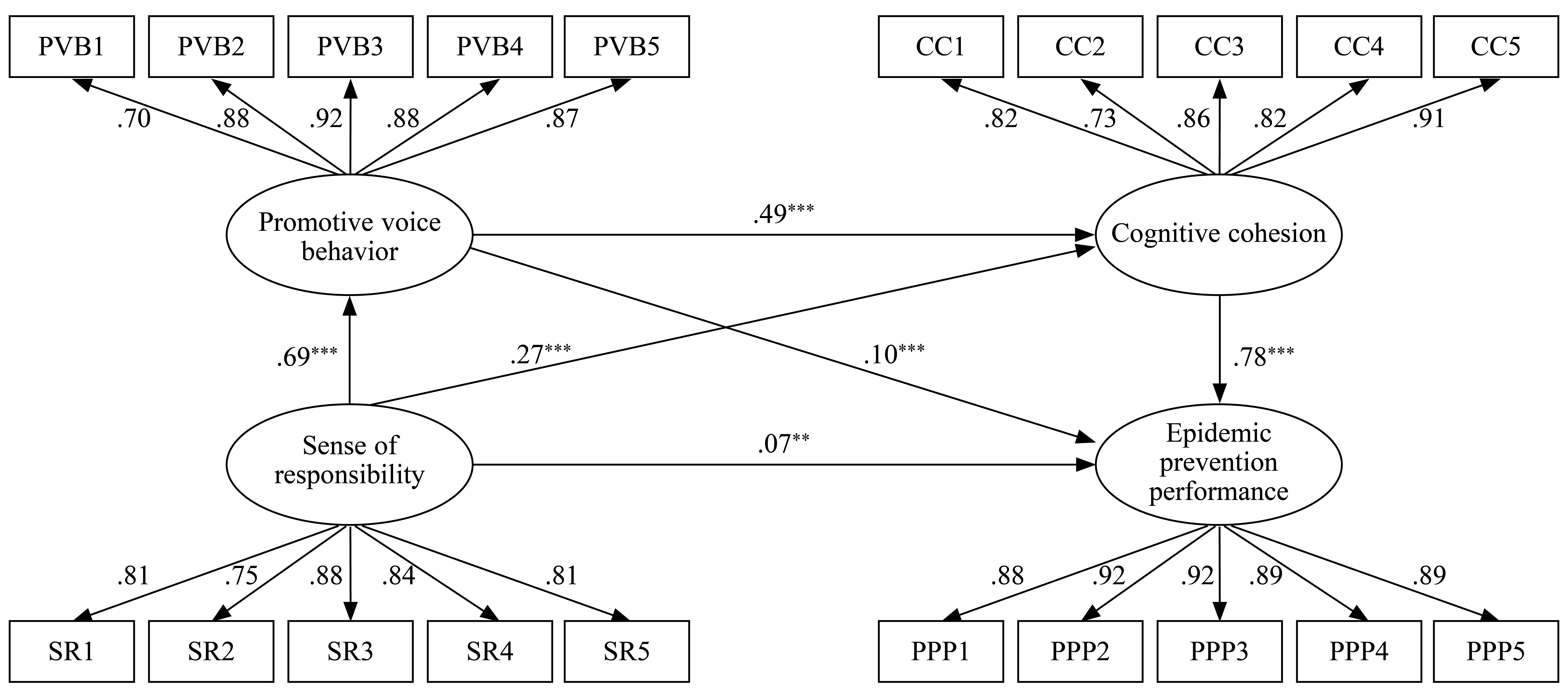

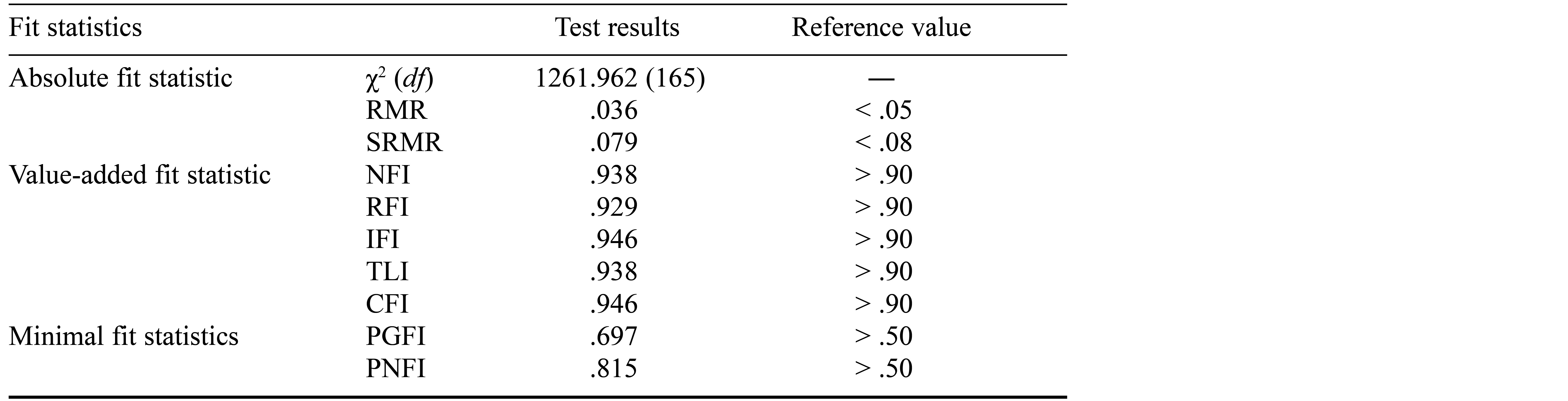

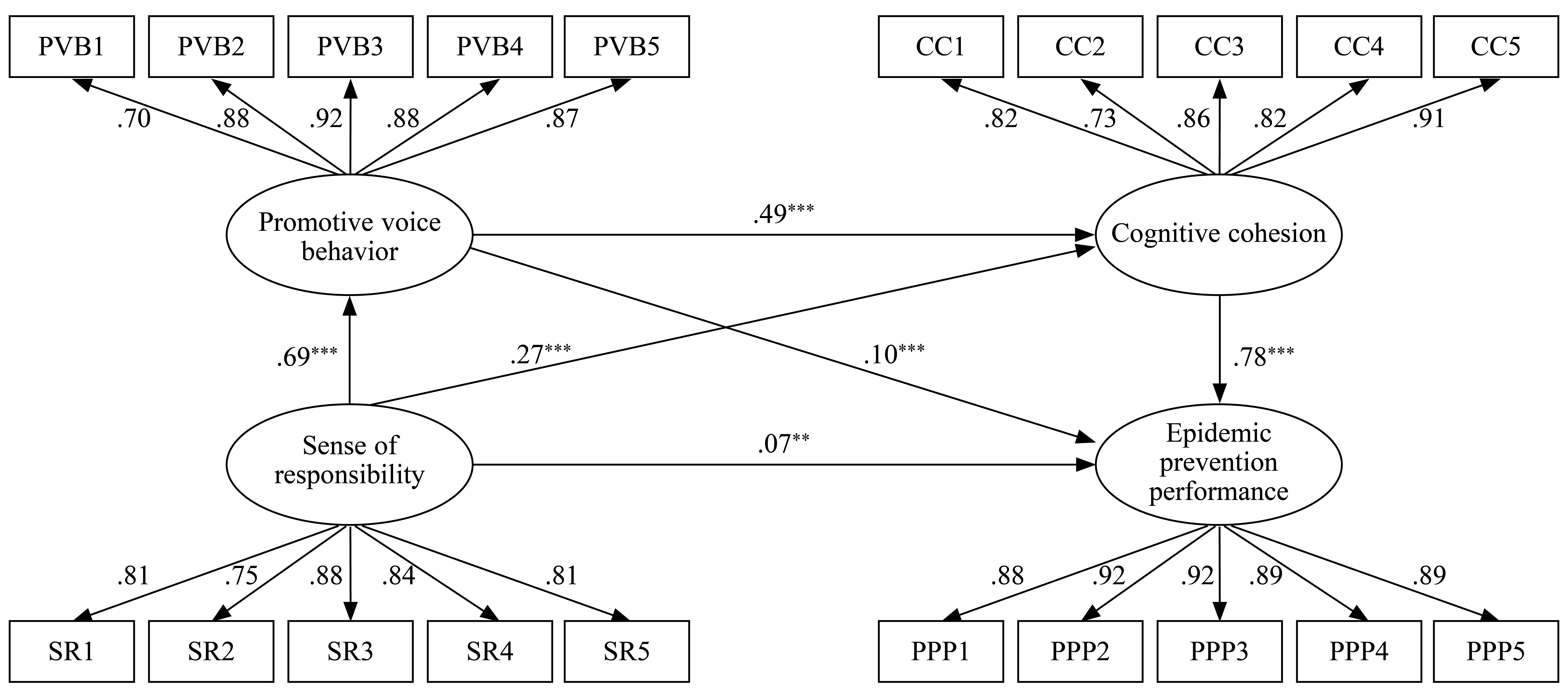

We used Amos 24.0 to construct a structural equation model for data path analysis. The research model of home pandemic prevention performance had a good fit to the data (see Table 3). The statistical test results for the model and the normalized path coefficients are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 3. Goodness of Fit of the Model

Note. RMR = root-mean-square residual; SRMR = standardized root-mean-square residual; NFI = normed fit index; RFI = relative fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; CFI = comparative fit index; PGFI = parsimonious goodness-of-fit index; PNFI = parsimonious normed fit index.

Figure 1. Chain Mediating Effect Model of College Students’ Sense of Responsibility and Performance of Pandemic Prevention at Home

Note. SR = sense of responsibility; PVB = promotive voice behavior; CC = family cognitive cohesion; PPP = pandemic prevention performance at home.

** p < .01. *** p < .001.

In this model we analyzed three mediating effects. The first was the path of sense of responsibility → promotive voice behavior → pandemic prevention performance, for which the direct effect was .07, the indirect effect was .07 (0.69 × 0.10), and the total effect was .14. The amount of variance accounted for was 50% (indirect effect = .07, total effect = .14). The second was the path of college students’ sense of responsibility → cognitive cohesion → pandemic prevention performance, for which the direct effect was .07, the indirect effect was .21 (0.27 × 0.78), the total effect was .28, and the amount of explained variance was 75%. The third was the chain mediation path of sense responsibility → promotive voice behavior → cognitive cohesion → pandemic prevention performance, for which the direct effect was .07, the indirect effect was .26 (0.69 × 0.49 × 0.78), the total effect was .33, and the amount of explained variance was 79%. To check if this was significant, we used the built-in bootstrapping function of Amos, setting the number of resamplings at 5,000 and calculating 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The results implied that the mediation effect was significant, 95% CI [0.468, 0.619], excluding zero. These results supported all four hypotheses.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

The results of this study indicate that college students’ sense of responsibility, promotive voice behavior, and family cognitive cohesion have significantly positive effects on pandemic prevention performance in their family home. This confirms the findings of related research showing that more highly conscientious people perform better in college and at work (Luo, 2007). Additionally, the participants in this study were aged between 18 and 20 years, and Chinese adolescents have a strong sense of family obligation (Wang et al., 2001).

We found that promotive voice behavior plays a mediating role in the relationship between students’ sense of responsibility and their pandemic prevention performance at home. Specifically, the stronger is college students’ sense of responsibility, the more likely they are to engage in promotive voice behavior, which then significantly and positively affects their pandemic prevention behavior at home. Previous studies have found that personality traits affect promotive voice behavior; for example, conscientiousness in the Big Five personality traits is positively correlated with voice behavior (Hackman & Wageman, 2005; Liang et al., 2012). In addition, in a dynamic environment, the active voice behavior of organizational members plays a positive role in improving organizational learning, and can further improve the operational efficiency of the organization and its level of attainment (Senge & Sterman, 1992). Promotive voice behavior has a direct positive effect on students’ pandemic prevention performance at home. In the fight against the pandemic, we found that the college students understand their responsibilities and actively present suggestions to improve the pandemic prevention performance at home. Therefore, promotive voice behavior plays a mediating role between college students’ sense of responsibility and their pandemic prevention performance at home.

Further, we found that family cognitive cohesion plays a mediating role in the relationship between college students’ sense of responsibility and their pandemic prevention performance at home. Specifically, the stronger is college students’ sense of responsibility, the higher is the level of family cognitive cohesion, which significantly and positively predicts their pandemic prevention behavior (Senge & Sterman, 1992). Having shared beliefs and values is the key to improving team performance (Mathieu et al., 2000; Xiang & Ye, 2013). Cognitive cohesion can effectively improve job performance. Furthermore, the enhancement of cohesion can improve the sense of ownership of team members and mobilize them to take the initiative. The enhanced sense of ownership caused by the improvement of cohesion will further unite team members (Senge & Sterman, 1992), indicating that college students’ sense of responsibility will further promote the enhancement of cohesion and thus improve their performance of pandemic prevention measures. Therefore, a stronger the sense of responsibility of college students is more conducive to enhancing family cognitive cohesion, thereby improving their performance of pandemic prevention at home.

Finally, we found that college students’ promotive voice behavior and cognitive cohesion play a chain mediation role in the relationship between sense of responsibility and pandemic prevention performance in the family home. In other words, college students’ sense of responsibility increases their promotive voice behavior in pandemic prevention performance, which then increases their cognitive cohesion in pandemic prevention and control, thus improving the effect of home pandemic prevention. On the basis of cognitive motivation theory, conscientiousness may affect job performance by influencing the cognitive motivation process, and performance expectation and goal selection act as mediating variables between conscientiousness and job performance (Gellatly, 1996). When people with a strong sense of responsibility are faced with risky, challenging behavior choices, they are more inclined than are those whose sense of responsibility is weaker to seize opportunities, actively face difficulties, and take action to achieve their goals (Shi, 2013). During their performance of pandemic prevention at home, college students with a strong sense of responsibility have realized the importance of pandemic prevention and internalized the whole-family pandemic prevention effort as their obligation to their family and society. They proactively publicize, supervise, and implement various measures for family pandemic prevention, and propose innovative suggestions to encourage family members to form the same values that positively influence pandemic prevention in their home. Thus, promotive voice behavior and family cognitive cohesion play a chain mediation role in the relationship between students’ sense of responsibility and their performance of pandemic prevention at home.

Practical Implications

Our results emphasize that college students, as a cohesive force between family and society, play an indispensable role in strengthening the social morality consciousness of family members and enhancing social cohesion. First, parents and teachers should cultivate college students’ sense of responsibility in family life, educating them to clarify their obligations and responsibilities in terms of family work and treatment of others. Second, the role of parents as exemplars entails them taking the initiative to participate in community volunteer services, as a way of teaching children to establish a conscious sense of responsibility for individuals, families, and society. Third, schools should take the role of responsibility training, attach importance to the cultivation of college students’ cognition of responsibility in ideological and political theory courses, and stimulate their sense of responsibility. Fourth, college students should be encouraged to take part in voluntary service, and college staff should further promote social practice activities such as supporting remote and poor areas through volunteer teaching activities and the three visits to the countryside, which is a program that involves a year of education and teaching management work carried out by college students in primary and middle schools in poor areas of central and western China. The program entails decentralization of resources and services in culture, science and technology, and health to rural areas, and the provision of support and services in culture and entertainment, the popularization of science and technology, and healthcare for farmers. Through participating in social surveys and other activities, college students can improve their understanding of social problems and enhance their sense of responsibility.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although we achieved the research purpose in this paper, there are some limitations. First, the area from which participants in the study were drawn was limited to five regions severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and, as such, the results may not be applicable to a larger region. Second, some background factors, such as national culture and family background, have not been fully considered. Third, the data were drawn from the self-assessment reports of the sample, which may be subjective to some extent. However, this study adds to the ongoing discussion about the diversity and possibility of individuals influencing team performance in families. Further study of college students from different regions, countries, and backgrounds is suggested to obtain rich sample data through more interviews, observations, community reports, and other channels, thereby enriching the current family performance development model.

References

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26.

Björnberg, Å., & Nicholson, N. (2007). The Family Climate Scales—Development of a new measure for use in family business research. Family Business Review, 20(3), 299–246.

Chen, W., Zhou, Q., Yang, M., Zhang, Y., & Zhong, L. (2019). Impact of knowledge service team identification on team performance: A cross-level dual mediation model [In Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Management, 16(8), 1153–1160.

Chen, Z., Ma, P., Zhang, X., & Min, Y. (2017). Cognitive cohesion, family commitment and organizational creativity [In Chinese]. South China Journal of Economics, 36(8), 8–28.

Deng, L., & Ding, Z. (2012). Entrepreneurial team characteristics, the interaction process and their effect on entrepreneurial performance [In Chinese]. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science Edition), 6, 13–20.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884.

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., & Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1089–1120.

Gellatly, I. R. (1996). Conscientiousness and task performance: Tests of a cognitive process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 474–482.

Gollan, P. J., & Wilkinson, A. (2007). Contemporary developments in information and consultation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(7), 1133–1144.

Hackman, J. R., & Wageman, R. (2005). A theory of team coaching. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 269–287.

Hong, C. (2020). Responsibilities and actions of universities in epidemic prevention and control [In Chinese]. Journal of Chinese Higher Education, 8, 28–29.

Huang, S., Han, M., Ning, C., & Lin, C. (2016). School identity promotes sense of responsibility in college students: The mediating role of self-esteem [In Chinese]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(6), 684–692.

Hung, H.-K., Yeh, R.-S., & Shih, H.-Y. (2012). Voice behavior and performance ratings: The role of political skill. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 442–450.

Jackson, S. E., Joshi, A., & Erhardt, N. L. (2003). Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management, 29(6), 801–830.

Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1854–1872.

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., Shanine, K. K., & Kacmar, K. M. (2017). Introducing the family: A review of family science with implications for management research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 309–341.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336.

Li, S. L., & Li, J. (2008). The intergenerational differences between college students and their parents in the information age—An empirical study on media use and social consciousness of Shanghai college students and their parents [In Chinese]. Journal of Journalism University, 95(1), 19–24.

Liang, J., & Farh, J.-L. (2008, June 19–22). Promotive and prohibitive voice behavior in organizations: A two-wave longitudinal examination [Paper presentation]. Third Conference of the International Association for Chinese Management Research, Guangzhou, China.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J.-L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92.

Luo, X. (2007). Study on the compilation and application of the College Students’ Responsibility Questionnaire (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Fujian Normal University.

Mathieu, J. E., Heffner, T. S., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2000). The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 273–283.

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extra role efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 403–419.

Motowildo, S. J., Borman, W. C., & Schmit, M. J. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 10(2), 71–83.

Senge, P. M., & Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 137–150.

Shi, Y. Y. (2013). The influence of organizational embeddedness on employee voice behavior: The mediating role of affective commitment and responsibility (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Central South University.

Stamper, C. L., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Work status and organizational citizenship behavior: A field study of restaurant employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 517–536.

Such, E., & Walker, R. (2004). Being responsible and responsible beings: Children’s understanding of responsibility. Children & Society, 18(3), 231–242.

Sun, J. (2006). The present situation, characteristics and educational countermeasures of high school students’ conscientiousness in Shandong Province (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Qufu Normal University.

Van Der Vegt, G. S., & Bunderson, J. S. (2005). Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: The importance of collective team identification. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 532–547.

Van Woerkom, M., & Sanders, K. (2010). The romance of learning from disagreement. The effect of cohesiveness and disagreement on knowledge sharing behavior and individual performance within teams. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(1), 139–149.

Wang, M.-P., Zhang, K., & Zhang, W.-X. (2001). Adolescents’ sense of family obligation in urban and rural areas [In Chinese]. Psychological Development and Education, 17(3), 28–32.

Xi, J.-P. (2019, April 30). Speech at the General Assembly to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the May 4th Movement [In Chinese].

Xiang, K., & Ye, L. (2013). The impact of team processes on shared mental models and organizational performance [In Chinese]. Seek, 7, 23–25.

Xu, L., & Li, L. (2019). The influence of team psychological capital on team innovation performance of universities’ major research and development project teams [In Chinese]. Journal of Higher Education Management, 13(1), 55–64.

Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 682–696.

Zhou, Q. (2020, April 4). Prevention and control of the epidemic calls for three kinds of public awareness [In Chinese]. Economic Daily.

Zhou, R. (2004). On the construction of enterprise cohesion [In Chinese]. Hubei Social Sciences, 9, 50–51.

Zhu, Y., & Akhtar, S., (2019). Leader trait learning goal orientation and employee voice behavior: The mediating role of managerial openness and the moderating role of felt obligation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2876–2900.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26.

Björnberg, Å., & Nicholson, N. (2007). The Family Climate Scales—Development of a new measure for use in family business research. Family Business Review, 20(3), 299–246.

Chen, W., Zhou, Q., Yang, M., Zhang, Y., & Zhong, L. (2019). Impact of knowledge service team identification on team performance: A cross-level dual mediation model [In Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Management, 16(8), 1153–1160.

Chen, Z., Ma, P., Zhang, X., & Min, Y. (2017). Cognitive cohesion, family commitment and organizational creativity [In Chinese]. South China Journal of Economics, 36(8), 8–28.

Deng, L., & Ding, Z. (2012). Entrepreneurial team characteristics, the interaction process and their effect on entrepreneurial performance [In Chinese]. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science Edition), 6, 13–20.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884.

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., & Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1089–1120.

Gellatly, I. R. (1996). Conscientiousness and task performance: Tests of a cognitive process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 474–482.

Gollan, P. J., & Wilkinson, A. (2007). Contemporary developments in information and consultation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(7), 1133–1144.

Hackman, J. R., & Wageman, R. (2005). A theory of team coaching. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 269–287.

Hong, C. (2020). Responsibilities and actions of universities in epidemic prevention and control [In Chinese]. Journal of Chinese Higher Education, 8, 28–29.

Huang, S., Han, M., Ning, C., & Lin, C. (2016). School identity promotes sense of responsibility in college students: The mediating role of self-esteem [In Chinese]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(6), 684–692.

Hung, H.-K., Yeh, R.-S., & Shih, H.-Y. (2012). Voice behavior and performance ratings: The role of political skill. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 442–450.

Jackson, S. E., Joshi, A., & Erhardt, N. L. (2003). Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management, 29(6), 801–830.

Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1854–1872.

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., Shanine, K. K., & Kacmar, K. M. (2017). Introducing the family: A review of family science with implications for management research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 309–341.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336.

Li, S. L., & Li, J. (2008). The intergenerational differences between college students and their parents in the information age—An empirical study on media use and social consciousness of Shanghai college students and their parents [In Chinese]. Journal of Journalism University, 95(1), 19–24.

Liang, J., & Farh, J.-L. (2008, June 19–22). Promotive and prohibitive voice behavior in organizations: A two-wave longitudinal examination [Paper presentation]. Third Conference of the International Association for Chinese Management Research, Guangzhou, China.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J.-L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92.

Luo, X. (2007). Study on the compilation and application of the College Students’ Responsibility Questionnaire (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Fujian Normal University.

Mathieu, J. E., Heffner, T. S., Goodwin, G. F., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2000). The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 273–283.

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extra role efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 403–419.

Motowildo, S. J., Borman, W. C., & Schmit, M. J. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 10(2), 71–83.

Senge, P. M., & Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 137–150.

Shi, Y. Y. (2013). The influence of organizational embeddedness on employee voice behavior: The mediating role of affective commitment and responsibility (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Central South University.

Stamper, C. L., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Work status and organizational citizenship behavior: A field study of restaurant employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 517–536.

Such, E., & Walker, R. (2004). Being responsible and responsible beings: Children’s understanding of responsibility. Children & Society, 18(3), 231–242.

Sun, J. (2006). The present situation, characteristics and educational countermeasures of high school students’ conscientiousness in Shandong Province (Master’s thesis) [In Chinese]. Qufu Normal University.

Van Der Vegt, G. S., & Bunderson, J. S. (2005). Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: The importance of collective team identification. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 532–547.

Van Woerkom, M., & Sanders, K. (2010). The romance of learning from disagreement. The effect of cohesiveness and disagreement on knowledge sharing behavior and individual performance within teams. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(1), 139–149.

Wang, M.-P., Zhang, K., & Zhang, W.-X. (2001). Adolescents’ sense of family obligation in urban and rural areas [In Chinese]. Psychological Development and Education, 17(3), 28–32.

Xi, J.-P. (2019, April 30). Speech at the General Assembly to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the May 4th Movement [In Chinese].

Xiang, K., & Ye, L. (2013). The impact of team processes on shared mental models and organizational performance [In Chinese]. Seek, 7, 23–25.

Xu, L., & Li, L. (2019). The influence of team psychological capital on team innovation performance of universities’ major research and development project teams [In Chinese]. Journal of Higher Education Management, 13(1), 55–64.

Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 682–696.

Zhou, Q. (2020, April 4). Prevention and control of the epidemic calls for three kinds of public awareness [In Chinese]. Economic Daily.

Zhou, R. (2004). On the construction of enterprise cohesion [In Chinese]. Hubei Social Sciences, 9, 50–51.

Zhu, Y., & Akhtar, S., (2019). Leader trait learning goal orientation and employee voice behavior: The mediating role of managerial openness and the moderating role of felt obligation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2876–2900.