Self-service versus human interaction in private consumption: The moderating role of brand personality

Main Article Content

We explored how consumer attitudes toward service delivery types (self-service technology vs. face-to-face) differ in a private consumption context depending on the brand personality (underdog brand vs. top-dog brand). Using banking service (Study 1) and hotel service (Study 2) scenarios, we empirically investigated the interaction effects between service delivery types and brand personalities on consumer attitudes. The results indicate that for humanized underdog brands consumers showed a more positive attitude toward self-service technologies than toward face-to-face services. However, for the top-dog brands there were no significant moderation effects. Thus, when managers in the marketing field are planning to regulate new directions for their service policy, they need to be very cautious by considering both consumption context and brand personality. We have theoretically and practically expanded the existing literature on service delivery by focusing on private consumption services.

Privacy is defined as “the right to be let alone” (Wang et al., 1998, p. 64). Sometimes, for reasons related to personal privacy, consumers may not want to be noticed by others when consuming (e.g., bank transactions that contain personal information, or a secret trip with a lover). In these cases, self-service technologies (SSTs) can be an optimal service method in that they are delivered without human interaction. In contrast to public consumption, which happens among a crowd, private consumption usually occurs alone or when the individual is accompanied by only a few people (Rodas & John, 2020). Thus, in the private consumption process, when a humanized brand is involved people may not fully enjoy their consumption experience and may feel uncomfortable. This is because a humanized brand may be considered as a living, breathing organism—a real human—which hinders consumers from enjoying their private consumption. Thus, we anticipated that consumers would prefer SSTs to face-to-face services when consuming private services, especially for underdog brands, as they are described as more humanized products than top-dog brands (Y. Kim et al., 2019). Specifically, consumers may feel anxious about humanized brands when sharing their private consumption information, as these brands are considered to have a mind and intention similar to that of humans (H.-Y. Kim & McGill, 2018).

Thus, in this study we explored how consumer attitudes toward SST versus face-to-face service delivery differ in the private consumption context depending on the brand personality (underdog brand vs. top-dog brand).

Theoretical Background

Before illustrating the empirical study results, we thoroughly reviewed the literature on service delivery types and the effects of anthropomorphized brand personality in the private consumption context.

Service Delivery Types

The development of technology has had a major impact on society and generated significant changes in the service industry (Weijters et al., 2007). The most representative change in this industry is the mode of service delivery. In the past, face-to-face interaction with employees has been an inevitable part of the service delivery process. However, high-technology-based SST reduces the need for staff and has even brought the advent of unmanned stores (Wu et al., 2019). Although the benefits of SST are obvious in terms of cost-effectiveness for business owners, the quality of SST has been questioned from the perspective of consumer experience (Meuter et al., 2003), especially in private consumption contexts such as finance and the hospitality industry (Ko, 2017). This is because during the private service process, human interaction is considered an essential element making customized quality services possible (Ko, 2017). For example, consumers may expect that SST cannot properly handle complex requirements. However, we proposed that even in the private consumption context, brand positioning may work as a critical factor to moderate consumers’ SST adoption. Consumers’ attitudes toward SST may differ in the private consumption context depending on how the brand is positioned. In the private consumption context, an adequate personal distance should be protected. When handling private business, such as bank account balances, consumers may consider sharing with a nonhuman entity, such as an SST, to be comfortable. This kind of refusal to interact with people may be revealed in the case of humanized brands in a specific case of private consumption. For example, consumers might want to avoid humanized brands because they may feel that their private consumption is being monitored by the brand with an intention and consciousness (Epley & Waytz, 2010). Thus, when using humanized brands in the private consumption context, we anticipated that consumers would prefer the SST service delivery type to the face-to-face type, despite the inconvenience of a lack of customization.

Underdog Brands in Private Consumption

An underdog brand is one of humble origin, with limited resources. Underdog brand positioning is an effective way to manipulate brand personality by imbuing the product with humanized features, which increases consumer empathy toward the brand (Jun et al., 2015). This positive consumer response is called the underdog effect (McGinnis & Gentry, 2009), and it captures consumers’ tendency to show a supportive attitude toward underdogs despite their low probability of winning competition against top dogs. The high level of identification between consumers and the underdog brand is considered the underlying mechanism to explain this positive attitude toward the underdog (Paharia et al., 2010). Compared to top-dog brands, which have privileged status and a range of resources, consumers tend to believe that underdogs face external disadvantages but that they have a spirit of passion and determination, which reflects two of the core elements for underdog positioning (Y. Kim & Park, 2020). Thus, consumers perceive the underdog brand as a much closer entity than a top-dog brand. In this study we predicted that in the private consumption context where maintaining an adequate amount of psychological distance is key to relieving consumer privacy concerns, underdog positioning would adversely affect consumer perception of the brand. If consumers feel judged by a humanized brand, they may choose to avoid it (Epley & Waytz, 2010). In sum, the consumer’s attitude toward private consumption of an underdog brand may be adversely affected if they assume the brand possesses highly anthropomorphized features.

However, using SSTs may decrease the adverse effects of underdog positioning in the private consumption context. Viewing SSTs in the frame of low-contact service, in the private consumption context lack of human interaction has become an advantage, especially for humanized brands, because a certain distance may be secured between the brand and the consumer (Wu et al., 2019). However, for top-dog brands, consumers may already feel an increased psychological distance toward the top dog compared with underdog brands. This is because consumers are less likely to identify with a privileged, well-resourced top dog than they are with an underdog brand of humble origin with limited resources (Paharia et al., 2010), which decreases the psychological distance from the underdog. Thus, discomfort that the consumer felt in the private consumption context, especially in the close psychological distance, such as in the case of the underdog, might not affect top dogs negatively. Finally, compared to underdog brands, for top-dog brands there may be less resistance to face-to-face services that require human interaction, even in the private consumption domain. Therefore, we hypothesized that in private consumption contexts involving underdog brands, consumers would show more favorable consumption attitudes toward self-service technologies than toward face-to-face services. For top-dog brands, however, we anticipated that there would be no significant difference between consumer attitudes toward the two service delivery types.

Study 1

Method

The aim of Study 1 was to determine a condition in which consumers may avoid face-to-face interactions with underdog brands. As consumers consider that underdog brands possess more humanlike features than top-dog brands do, for private consumption they may prefer SST rather than face-to-face interactions.

Participants

We recruited 350 participants in the US (209 women, 59.71% and 141 men, 40.29%; Mage = 34.27 years, SD = 11.90, range = 18–82) via the Prolific Academic online panel service, and randomly assigned them to one of four conditions in a 2 (service delivery type: face-to-face vs. SST) × 2 (brand biography: underdog vs. top dog) between-subjects design. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University (1908/002-013) for research involving human participants.

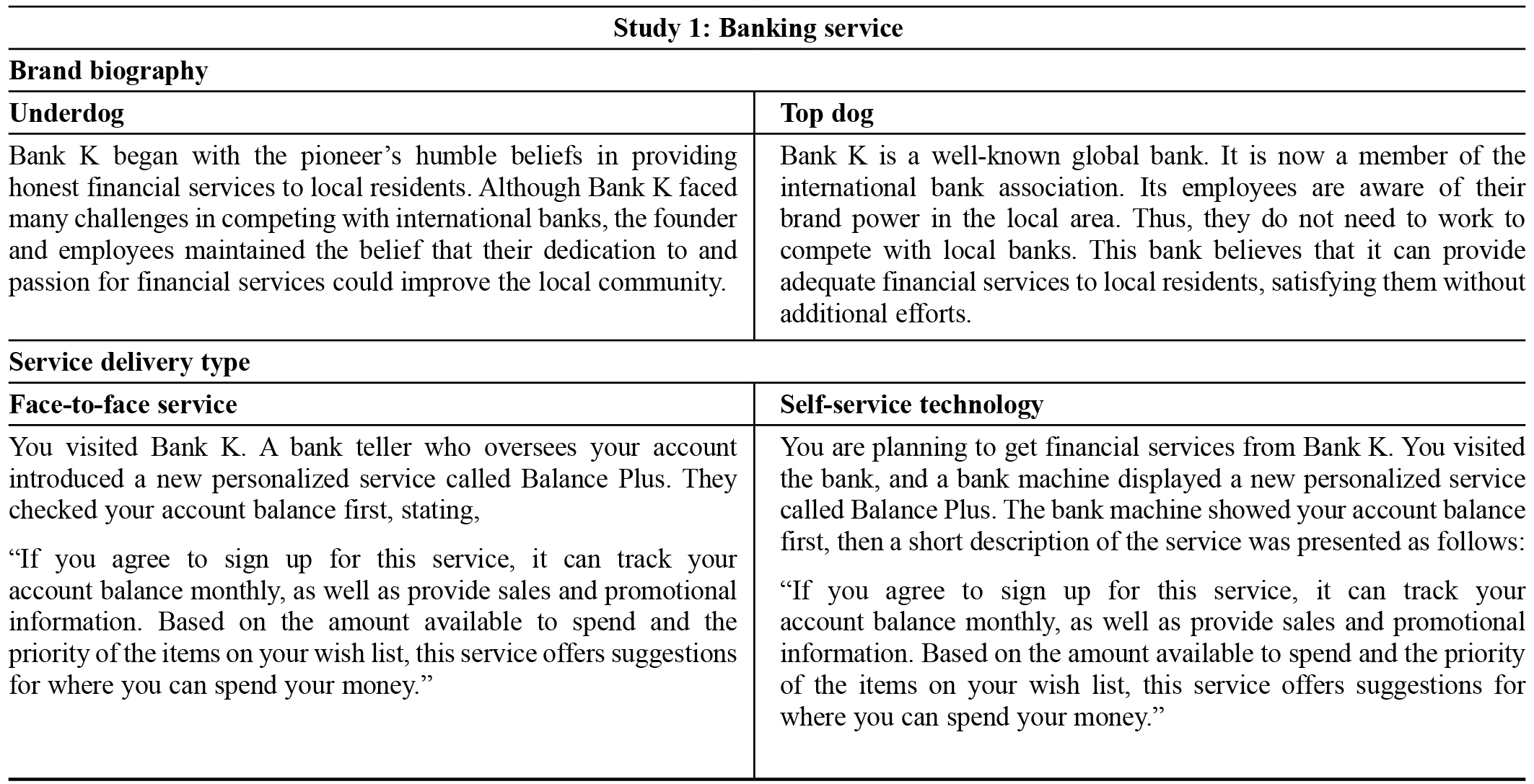

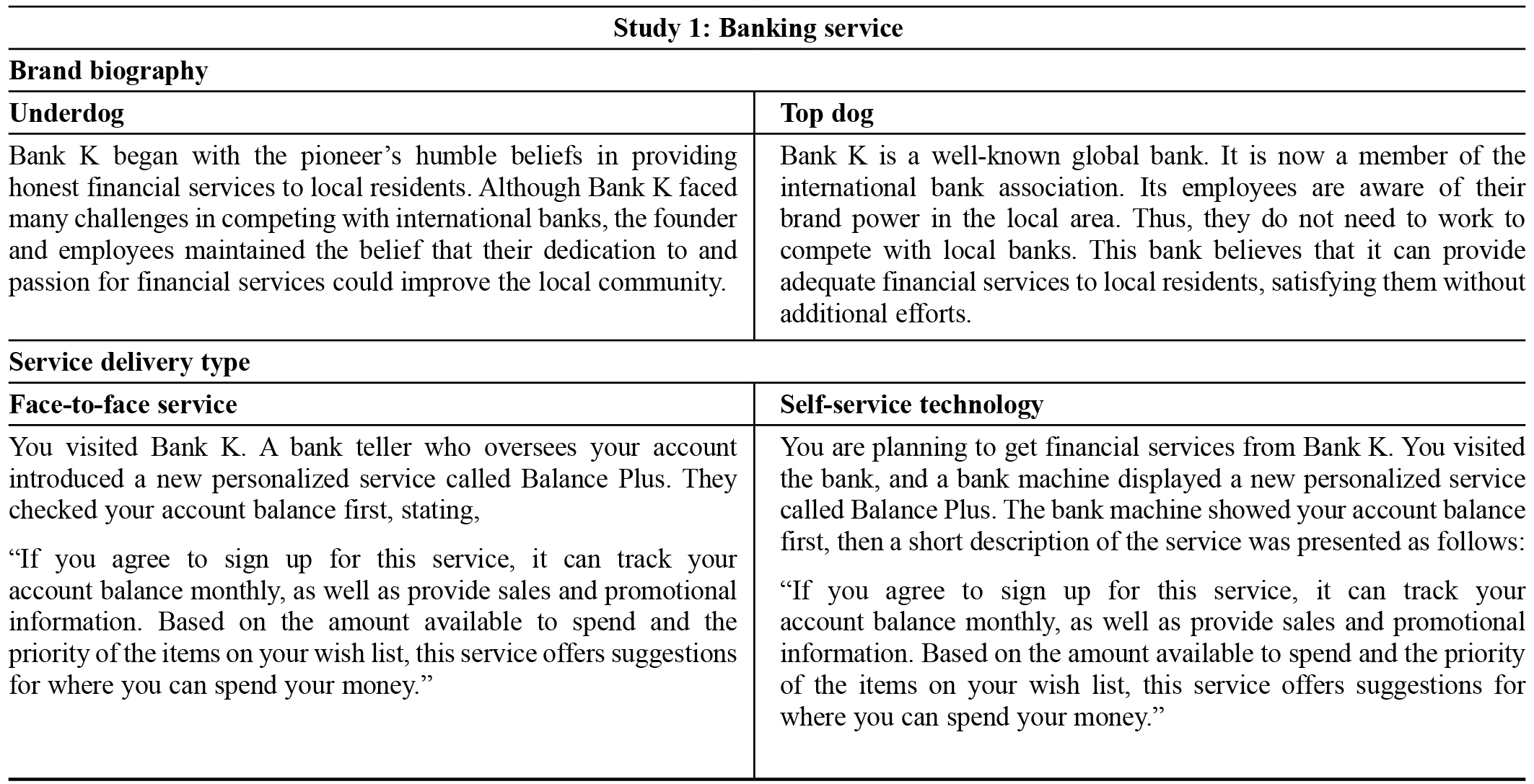

Procedure

After reading one of two brand biographies, participants were presented with a face-to-face service or SST scenario. We adopted a banking service (H.-Y. Kim & McGill, 2018) in the context of private consumption (see Appendix A). For the face-to-face service, the participants read a description of being introduced to a new banking service by a bank teller. In the SST scenario, the participants read about introduction to the same banking service by an automated machine. The new fictitious banking service was called Balance Plus, and was described as tracking a checking account balance monthly and providing information on sales and promotions. After reading general information about Balance Plus, the participants read that they could be provided with a more personalized service if they allowed the new service to connect to their personal accounts and share their shopping wish list. After reading the description, the participants evaluated their willingness to use the new service (H.-Y. Kim & McGill, 2018) by answering the following two questions: 1) “How much do you want to connect your personal bank account with this new banking service?” and 2) “To what extent are you willing to connect your personal shopping wish list with this new banking service?” Then the participants responded to the manipulation check measures on their perception of brand personality (Paharia et al., 2010): 1) “Brand A has passion and determination” and 2) “Brand A has restrictions from external disadvantage.” Additionally, consumers considered the type of service delivery: 1) “In the scenario a human employee took your order” and 2) “In the scenario you didn’t have any interaction with employees in the bank.” All questions and items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Results

Manipulation Checks

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the manipulation check for service delivery type indicated that the participants assigned a higher score to the item “Ordering from a human employee” for the face-to-face service (M = 5.92, SD = 1.50) than they did for SST (M = 2.69, SD = 1.95), F(1, 348) = 299.23, p < .001. They also assigned a lower score for the item “No human interaction exists in the service process” for the face-to-face service (M = 2.30, SD = 1.91) than for SST (M = 5.08, SD = 2.19), F(1, 348) = 160.52, p < .001. We performed the same ANOVA for brand personality and found that the participants perceived the scenarios as intended. Underdog brands were perceived to have greater passion and determination (M = 5.13, SD = 1.42) than top-dog brands did (M = 3.81, SD = 1.71), F(1, 348) = 62.20, p < .001, and greater external disadvantage (M = 4.61, SD = 1.55) than the top-dog brands did (M = 3.23, SD = 1.58), F(1, 348) = 68.28, p < .001.

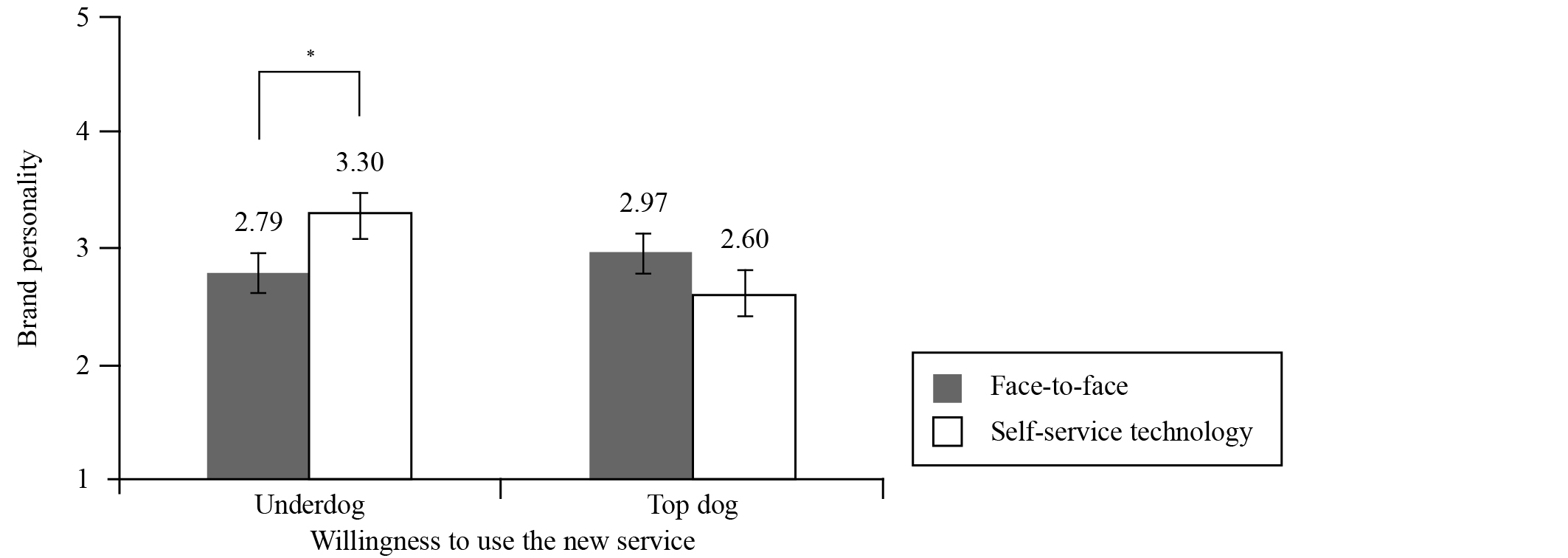

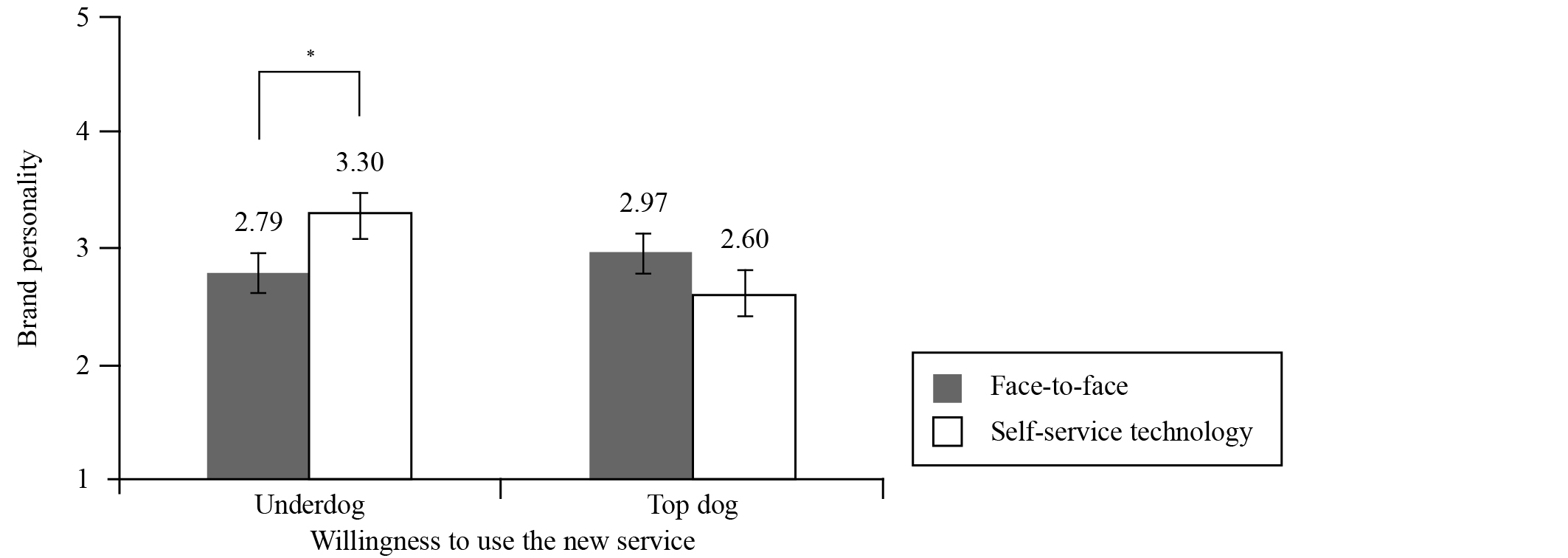

Willingness to Use the New Service

A 2 × 2 ANOVA of willingness to use the new service (α = .92) yielded a significant two-way interaction, F(1, 346) = 5.23, p = .023, for two main effects (Figure 1). For the underdog brand, the participants indicated greater willingness to use the service when human interaction was not involved (M = 3.30, SD = 1.98) than when human interaction was involved (M = 2.79, SD = 1.73), t(346) = 1.86, p = .064, whereas for the top-dog brand no significant difference was found in willingness to use the service regardless of whether human interaction was involved (M = 2.97, SD = 1.78) or not involved (M = 2.60, SD = 1.69), t(346) = 1.38, p > .156.

Figure 1. Effects of Brand Personality and Service Type on Willingness to Use the New Service

Note. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals around the means. SST = self-service technology.

* p < .07.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that in the private consumption context, participants were reluctant to receive services from human employees, especially for the underdog brand. Reduced psychological distance initiated by brand positioning may affect consumers’ willingness to use a new service, depending on the service delivery type. Obtaining face-to-face service from an underdog brand may cause discomfort, which negatively affects consumers’ intention to use the service.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Study 2 was designed to replicate Study 1 in a different consumption context, hotel service, and to further generalize the dependent variable to evaluate consumer attitudes toward the brand. We recruited 104 participants in the US (71 women, 68.27% and 33 men, 31.73%; Mage = 33.85 years, SD = 10.52, range = 18–63) via the Prolific Academic online panel service and randomly allocated them to one of four conditions in a 2 (service delivery type: face-to-face service vs. SST) × 2 (brand biography: underdog vs. top dog) between-subjects design. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University (1908/002-013) for research with human participants.

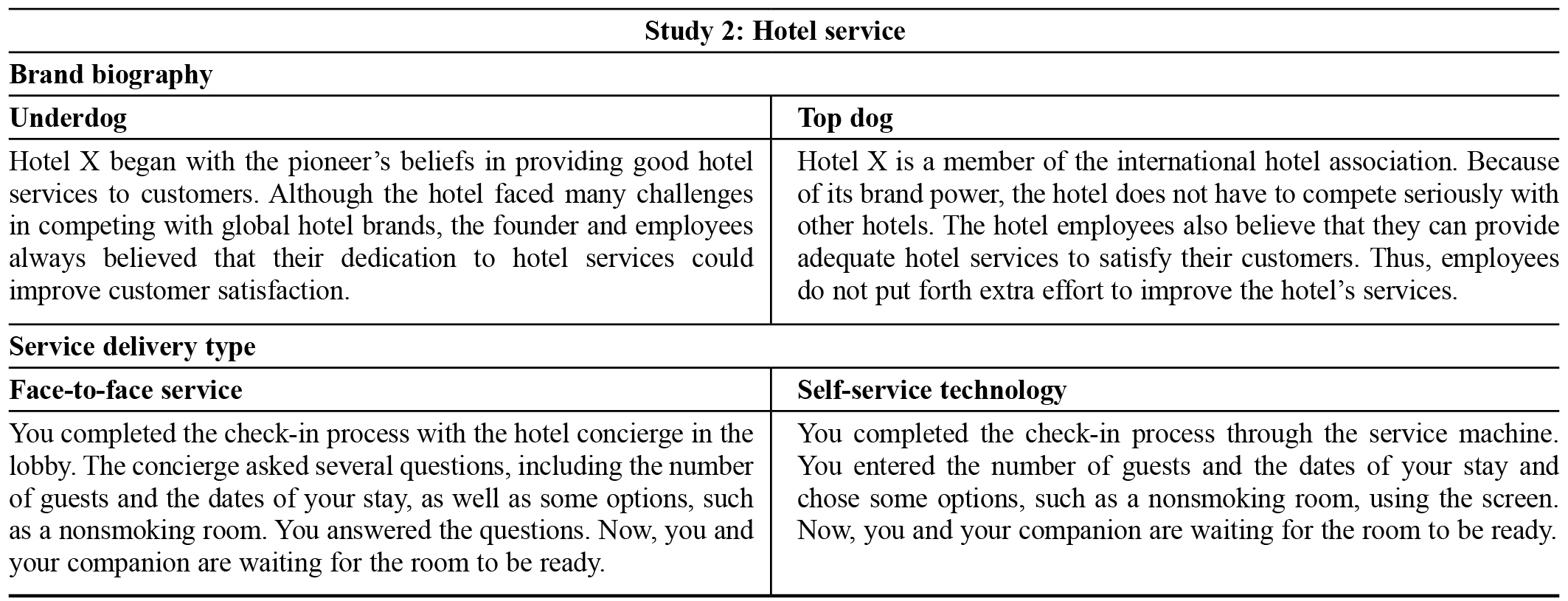

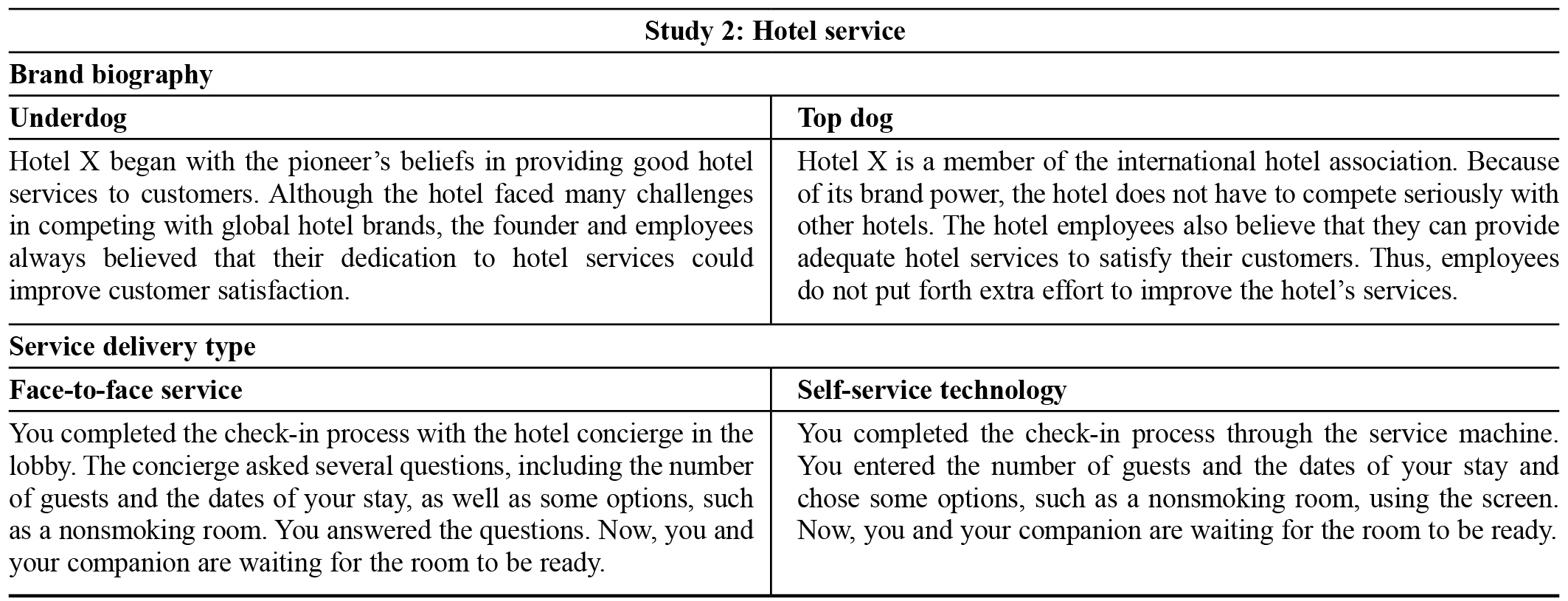

Procedure

In Study 2, we adopted a hotel service in a private consumption context (see Appendix B). For the face-to-face service, participants read about a check-in process in which they interacted with a hotel concierge. For the SST condition, participants read about using an automatic check-in machine. After reading the description, the participants evaluated their consumer attitude toward the hotel using questions adapted from Bidmon (2017) that were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much): 1) “How much do you like this (Brand A) hotel?” and 2) “How much would you like to revisit this (Brand A) hotel?” Then, the same manipulation check items as in the previous study were used to confirm that the scenario was perceived as intended.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Results of a one-way ANOVA of the manipulation check for service delivery type indicate that the participants who read the face-to-face service scenario assigned a higher score (M = 6.23, SD = 0.95) for “Ordering from a human employee” than did those who read the SST scenario (M = 1.36, SD = 1.01), F(1, 102) = 633.55, p < .001. The participants assigned a lower score on the “No human interaction exists in the service process” for the face-to-face scenario (M = 1.93, SD = 1.39) than for the SST scenario (M = 5.52, SD = 2.37), F(1, 102) = 90.05, p < .001. When we performed the same ANOVA for the brand personality manipulation check, the results show that brand personality was manipulated as intended. The underdog brand received higher scores for passion and determination (M = 5.15, SD = 1.48) than did the top-dog brand (M = 4.10, SD = 1.81), F(1, 102) = 10.09, p = .002, and the underdog brand also received higher scores for external disadvantage (M = 3.74, SD = 1.58) than the top-dog brand did (M = 2.79, SD = 1.59), F(1, 102) = 9.13, p = .003.

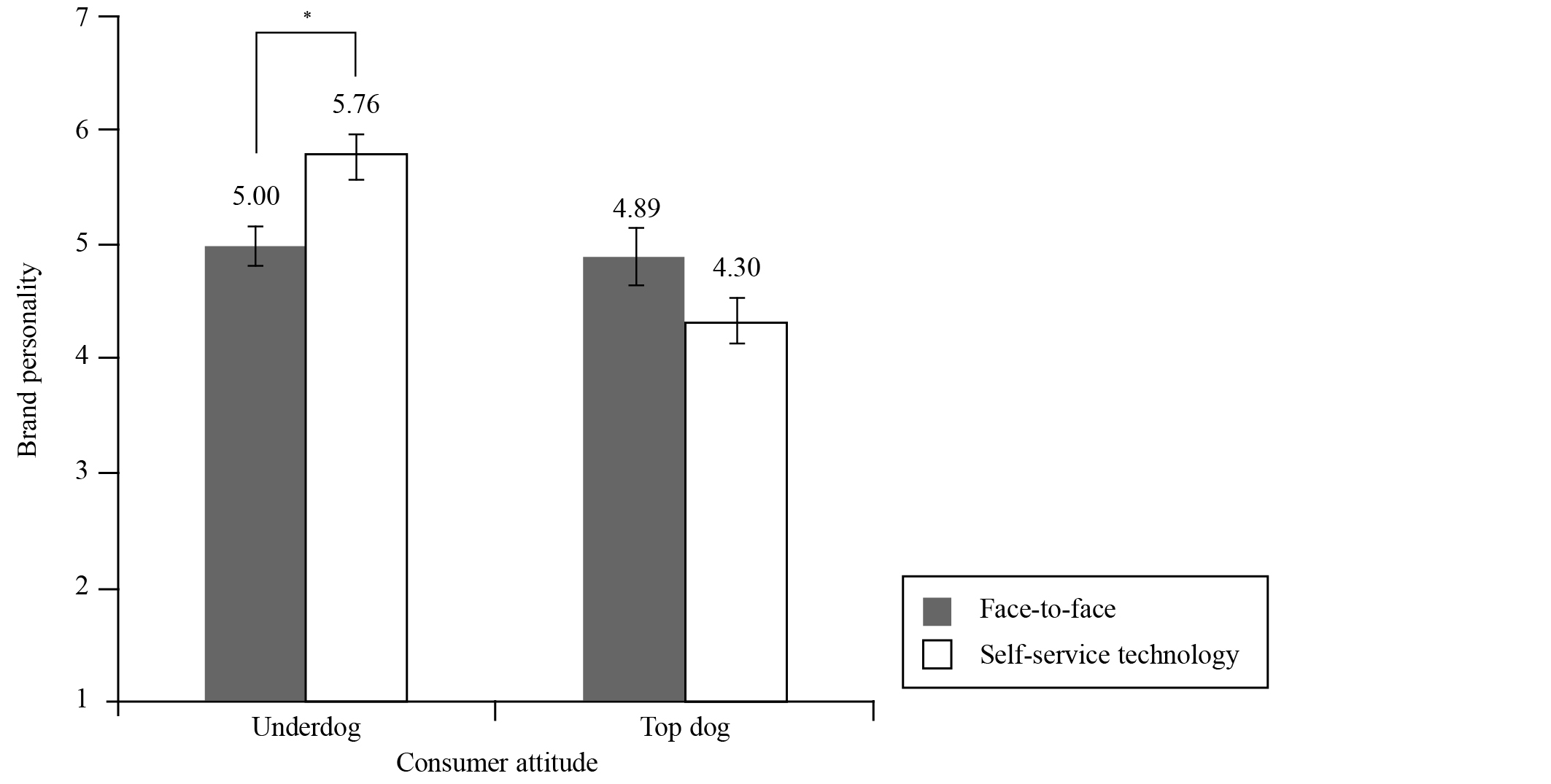

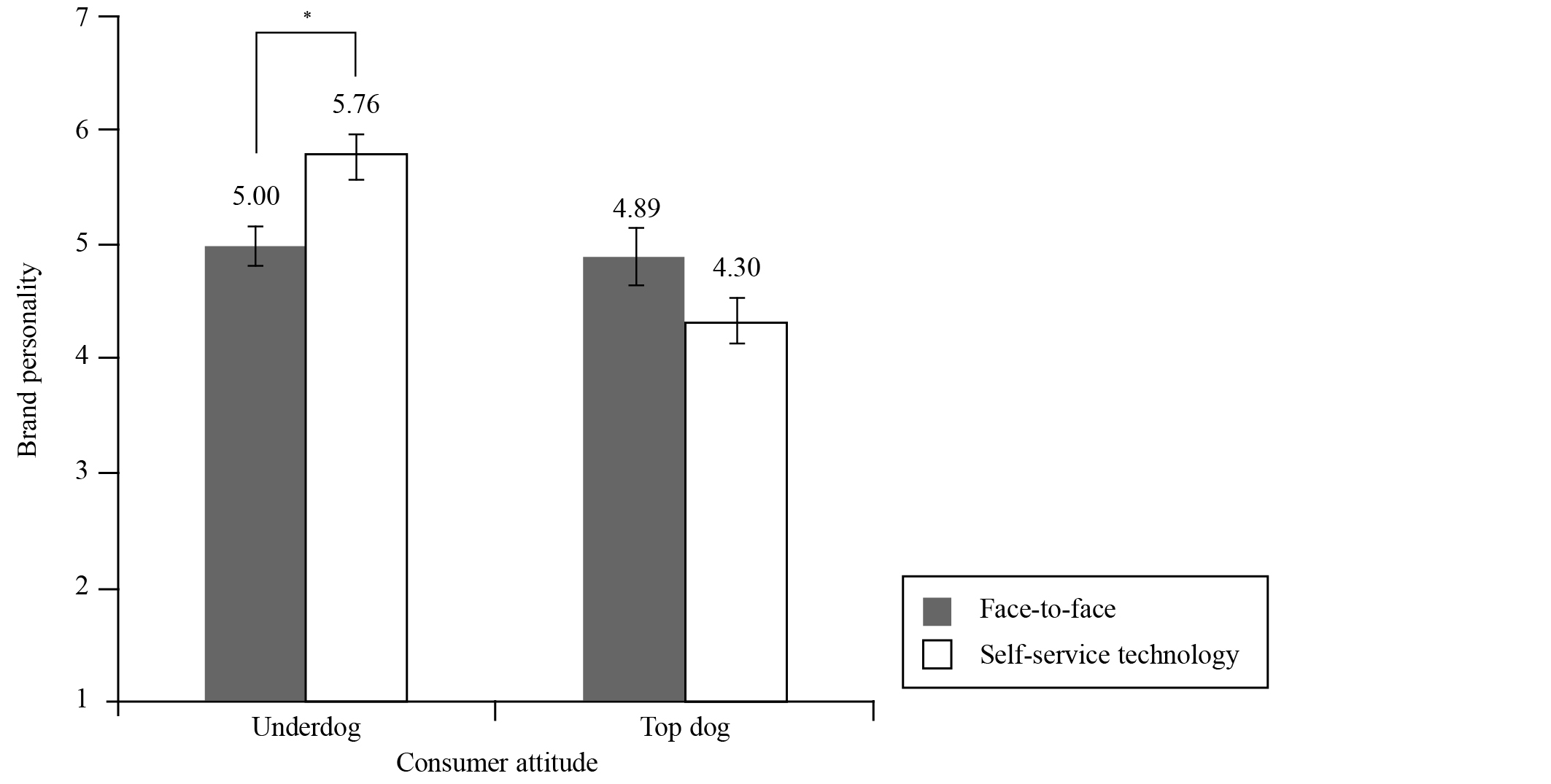

Consumer Attitude

A 2 × 2 ANOVA of consumer attitude (α = .85) revealed a significant two-way interaction, F(1, 100) = 7.21, p = .008 for the two main effects (Figure 2). For the underdog brand, participants showed a more positive consumer attitude when the service did not involve human interaction (M = 5.76, SD = 0.98) than when it did involve human interaction (M = 5.00, SD = 1.36), t(100) = 2.06, p = .042. Conversely, for the top-dog brand, there was no significant difference in consumer attitude whether human interaction was involved (M = 4.89, SD = 1.22) or not involved (M = 4.30, SD = 1.38), t(100) = 1.73, p = .087.

Figure 2. Effects of Brand Personality and Service Type on Consumer Attitude

Note. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals around the means; SST = self-service technology.

* p < .07.

Discussion

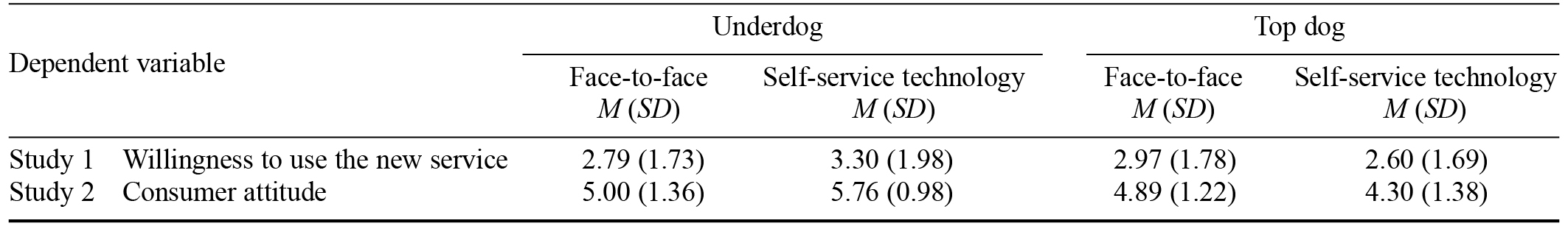

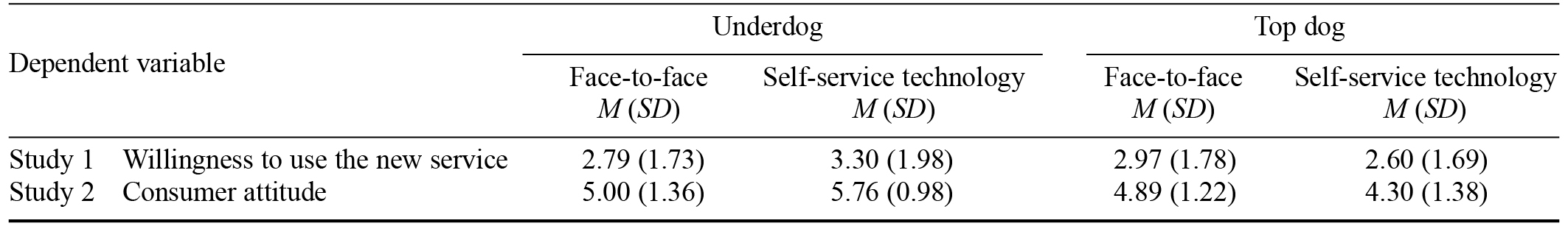

The Study 2 results replicate those of Study 1, in that participants were less likely to be willing to use hotel services offered by human employees when the hotel was described as an underdog brand. However, for the top-dog brand, the type of service delivery did not affect consumer attitudes. Table 1 presents a summary of the statistical results for both studies.

Table 1. Statistical Summary of Results in Studies 1 and 2

Note. SST = self-service technology.

General Discussion

The findings in the two studies were consistent. In the context of private consumption, for underdog brands the attitude of participants was more favorable toward SSTs than toward face-to-face services, whereas there was no significant difference between their attitude toward the two service delivery types for top-dog brands. Our results offer several theoretical contributions and practical implications. First, the findings suggest brand biography as a new important factor in the service literature, in that in a private consumption context, the favorability of consumers’ attitude toward service delivery types can differ depending on the brand biography. The results also provide practical implications for marketers, in that manipulating brand positioning may work as a critical factor affecting consumer preference for type of service delivery. Second, in this study we incorporated brand positioning and service delivery types, and investigated their effects in different private consumption contexts. When consumers’ privacy is important, underdog brands may make consumers feel that their personal realm is invaded, because they perceive underdogs as relational and humanlike objects (Y. Kim et al., 2019). Ultimately, this type of underdog branding makes consumers prefer SSTs and hesitate to obtain services from human employees. Third, we manipulated brand humanized personality by using brand biography rather than the visual appearance of the product and/or brand logos. Thus, when managers in the marketing field are planning to regulate new directions for their service policy, depending on the service sector or context, they can adjust the brand position cost-effectively.

This study has several limitations. First, our scenarios were limited to banking and hotel service contexts. In the future, these results could be tested in other service domains (e.g., purchasing women’s personal products in a convenience store) to generalize the findings with a larger sample size. Moreover, further research can be conducted to determine the underlying mechanism to explain the results of interaction effects between brand personality and service delivery type. In addition, we did not suggest solutions in the private consumption context for humanized brands to increase consumer satisfaction when served with human employees. Future research can be conducted to provide concrete guidance for management of underdog brands by suggesting strategies to achieve this.

We found that in the context of private consumption, the positive underdog effect did not lead to the brand benefitting from the empathy and closeness that the consumer perceives with the underdog brand. Because of the brand’s humanlike features, consumers were more cautious in responding to the brand and its service. Therefore, in determining types of service delivery and in regulating new services for highly humanized brands, marketers should be more careful than they are in determining delivery of nonhumanized brands.

References

Bidmon, S. (2017). How does attachment style influence the brand attachment – brand trust and brand loyalty chain in adolescents? International Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 164–189.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1172404

Epley, N., & Waytz, A. G. (2010). Mind perception. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., pp. 498–541). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy001014

Jun, S., Sung, J., Gentry, J. W., & McGinnis, L. P. (2015). Effects of underdog (vs. top dog) positioning advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 34(3), 495–514.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.996199

Kim, H.-Y., & McGill, A. L. (2018). Minions for the rich? Financial status changes how consumers see products with anthropomorphic features. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 429–450.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy006

Kim, Y., & Park, K. (2020). When the underdog positioning backfires! The effects of ethical transgressions on attitudes toward underdog brands. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1988.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01988

Kim, Y., Park, K., & Lee, S. S. (2019). The underdog trap: The moderating role of transgression type in forgiving underdog brands. Psychology & Marketing, 36(1), 28–40.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21155

Ko, C.-H. (2017). Exploring how hotel guests choose self-service technologies over service staff. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 9(3), 16–27. https://bit.ly/3EHq6A5

McGinnis, L. P., & Gentry, J. W. (2009). Underdog consumption: An exploration into meanings and motives. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 191–199.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.026

Meuter, M. L., Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., & Roundtree, R. (2003). The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. Journal of Business Research, 56(11), 899–906.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00276-4

Paharia, N., Keinan, A., Avery, J., & Schor, J. B. (2010). The underdog effect: The marketing of disadvantage and determination through brand biography. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 775–790.

https://doi.org/10.1086/656219

Rodas, M. A., & John, D. R. (2020). The secrecy effect: Secret consumption increases women’s product evaluations and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(6), 1093–1109.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz041

Wang, H., Lee, M. K. O., & Wang, C. (1998). Consumer privacy concerns about Internet marketing. Communications of the ACM, 41(3), 63–70.

https://doi.org/10.1145/272287.272299

Weijters, B., Rangarajan, D., Falk, T., & Schillewaert, N. (2007). Determinants and outcomes of customers’ use of self-service technology in a retail setting. Journal of Service Research, 10(1), 3–21.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507302990

Wu, H.-C., Ai, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-C. (2019). Experiential quality, experiential psychological states and experiential outcomes in an unmanned convenience store. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 409–420.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.07.003

Appendix A: Scenarios for Study 1

Appendix B: Scenarios for Study 2

Bidmon, S. (2017). How does attachment style influence the brand attachment – brand trust and brand loyalty chain in adolescents? International Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 164–189.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1172404

Epley, N., & Waytz, A. G. (2010). Mind perception. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., pp. 498–541). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy001014

Jun, S., Sung, J., Gentry, J. W., & McGinnis, L. P. (2015). Effects of underdog (vs. top dog) positioning advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 34(3), 495–514.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.996199

Kim, H.-Y., & McGill, A. L. (2018). Minions for the rich? Financial status changes how consumers see products with anthropomorphic features. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 429–450.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy006

Kim, Y., & Park, K. (2020). When the underdog positioning backfires! The effects of ethical transgressions on attitudes toward underdog brands. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1988.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01988

Kim, Y., Park, K., & Lee, S. S. (2019). The underdog trap: The moderating role of transgression type in forgiving underdog brands. Psychology & Marketing, 36(1), 28–40.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21155

Ko, C.-H. (2017). Exploring how hotel guests choose self-service technologies over service staff. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 9(3), 16–27. https://bit.ly/3EHq6A5

McGinnis, L. P., & Gentry, J. W. (2009). Underdog consumption: An exploration into meanings and motives. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 191–199.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.026

Meuter, M. L., Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., & Roundtree, R. (2003). The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. Journal of Business Research, 56(11), 899–906.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00276-4

Paharia, N., Keinan, A., Avery, J., & Schor, J. B. (2010). The underdog effect: The marketing of disadvantage and determination through brand biography. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 775–790.

https://doi.org/10.1086/656219

Rodas, M. A., & John, D. R. (2020). The secrecy effect: Secret consumption increases women’s product evaluations and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(6), 1093–1109.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz041

Wang, H., Lee, M. K. O., & Wang, C. (1998). Consumer privacy concerns about Internet marketing. Communications of the ACM, 41(3), 63–70.

https://doi.org/10.1145/272287.272299

Weijters, B., Rangarajan, D., Falk, T., & Schillewaert, N. (2007). Determinants and outcomes of customers’ use of self-service technology in a retail setting. Journal of Service Research, 10(1), 3–21.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507302990

Wu, H.-C., Ai, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-C. (2019). Experiential quality, experiential psychological states and experiential outcomes in an unmanned convenience store. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 409–420.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.07.003

Figure 1. Effects of Brand Personality and Service Type on Willingness to Use the New Service

Note. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals around the means. SST = self-service technology.

* p < .07.

Figure 2. Effects of Brand Personality and Service Type on Consumer Attitude

Note. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals around the means; SST = self-service technology.

* p < .07.

Table 1. Statistical Summary of Results in Studies 1 and 2

Note. SST = self-service technology.

This research was financially supported by a grant from Seoul Women&rsquo

s University (2021-0429)

the Center for Happiness Studies at Seoul National University (0404-20190002)

the Institute of Management at Seoul National University

and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5A2A01050564).

Kiwan Park, College of Business Administration, Seoul National University, 1 Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea. Email: [email protected], or Yaeri Kim, Department of Data Science, Seoul Women’s University, 621 Hwarang-ro, Nowon-gu, Seoul 01797, Republic of Korea. Email: [email protected]