Impact of night markets on residents’ quality of life

Main Article Content

There is a lack of discussion on the impact of night tourism activities on the quality of life of residents in the area where these activities are held. We adopted the Q method to explore the effect of the night market in Taiwan on residents in the area from the perspective of 4 groups: Long-term neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market, residents who live in the area where the night market is held, residents who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors, and residents who have integrated the night market into their own life. We discuss and address the conflicts between the perspectives of these groups using social disruption theory, social exchange theory, and empathy. Implications of the findings are described along with directions for future research.

When travelers want to experience the local culture in a new place they often go to the local market. According to statistics from a tourist spending and trends survey (Taiwan Tourism Bureau, 2016), the night market is the most important and popular tourist attraction in Taiwan. Meister in The Washington Post (2011) and Hsu in The New York Times (2013) have both reported that the night market is a great display of Taiwan’s unique culture. The night market, just as its name implies, is a market that operates at night. Night markets are distributed in both urban and rural areas, with unique consumption activities, snacks, displays, and commodities, as well as negotiable prices (Lee, Chang, Hou, & Lin, 2008). Night markets have features that differentiate them from the morning markets. Yu (2004) used the term renao to describe night markets, which is the atmosphere of a night market being hot and noisy, with active interaction among people, brilliant neon lights, loud music, and crowds, all of which convey a great sense of energy (see also Ackerman & Walker, 2012; Pottie-Sherman, 2013). Strolling through and socializing in night markets are also features that differentiate them from morning markets (Yu, 2004). Because of the unique appeal of night markets, previous researchers (e.g., Ackerman & Walker, 2012; Chang & Chiang, 2006; Lee et al., 2008) have focused on tourists to find out about their motivation and experience when visiting these markets, and to establish how to give them better memories and thus boost tourism.

However, the impact on residents (Hunter, 2013; Rivera, Croes, & Lee, 2016) has long been ignored. Although night markets benefit their neighborhood, they also generate costs (Pottie-Sherman, 2013). For example, some residents describe night markets as being chaotic, and would much prefer their neighborhood to be quiet and orderly (Yu, 2004). Moreover, previous researchers have shown that many problems, such as violence, drug abuse, sexual activities, and class-based issues are common occurrences in night-time economic entities (see, e.g., Bishop & Robinson, 1999; Chatterton & Hollands, 2002). For example, Amsterdam and London have serious noise and traffic problems at night (Bolaños-Briceño & Ariza-Marin, 2017). As a result, because residents in a night market area are the stakeholders bearing the heaviest costs, this aspect of the markets is worthy of further study. Different voices should be balanced in discussions, so that good decisions can be made by paying attention all interest groups (Elliott, 1998; Mason, 2003). Decisions made without residents’ participation deprive them of rights and will further irritate them and, thus, disrupt the community (Hunter, 2013). An understanding of how residents feel and how they are affected by tourism-related issues would help to solve such problems.

Residents’ quality of life (QOL) is an indicator of the impact of tourism on their lives (Andereck, Valentine, Knopf, & Vogt, 2005; Uysal, Perdue, & Sirgy, 2012; Uysal, Sirgy, Woo, & Kim, 2016). Residents’ QOL is a multidimensional concept that reflects their subjective views of their lives. Because of its multifaceted nature, until recently, residents’ definitions of QOL have been quite diverse (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011). Moscardo (2009) described residents’ QOL as their perceived satisfaction with the environment in which they live, whereas Andereck and Nyaupane (2011) defined it as referring to “one’s satisfaction with life and feelings of contentment or fulfillment with one’s experience in the world” (p. 248). More recently, Ivlevs (2017) proposed that people’s QOL should be captured from a holistic perspective, comprising both cognitive (e.g., global life satisfaction) and affective (e.g., a range of emotions, from joy to misery) components. As previous researchers have tended to conceptualize QOL as either cognitive or affective, prior measures have produced conflicting results (Ivlevs, 2017). We adopted Ivlevs’ (2017) definition, as many issues that we analyzed were identified from a comprehensive narration of the residents’ daily lives; thus, inevitably, cognitive and affective elements interacted.

However, as the impact of tourism activities on residents’ QOL is progressive and complicated (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011), their opinions are quite complex. As such, an in-depth exploration of residents’ opinions that allows them to express their mental maps, should be conducted (Hunter, 2013). Most previous researchers have used quantitative rather than qualitative methods to explore the impact of tourism on residents’ QOL (Magnini, Ford, & LaTour, 2012). However, using only a quantitative method makes it difficult to determine the significance of subtle changes in the formation of attitudes and—in the context of this study—the perceived impact on tourism on residents’ QOL (Deery, Jago, & Fredline, 2012). As Hollinshead (2007) stated that the Q method (Dennis & Goldberg, 1996) was developed to explore respondents’ opinions from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives, we decided to use this method. Use of the Q method allowed us to obtain an in-depth understanding of residents’ thoughts and motivation, which may give us insight into innovative ways to increase residents’ QOL (Magnini et al., 2012). Further, the quantitative advantages of the Q method enrich the research interpretation in this context (Wijngaarden, 2017). Thus, our research aim was to examine how night markets impact on the QOL of groups of residents with different perspectives, and to determine how to enhance residents’ QOL.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We used the Q method to collect and analyze data from participants, who agreed to the publication of the interview results. We followed four steps: (a) Q concourse and Q set, (b) P set (sample), (c) Q-sorting, and (d) mathematical and interpretive analysis of Q-sorting.

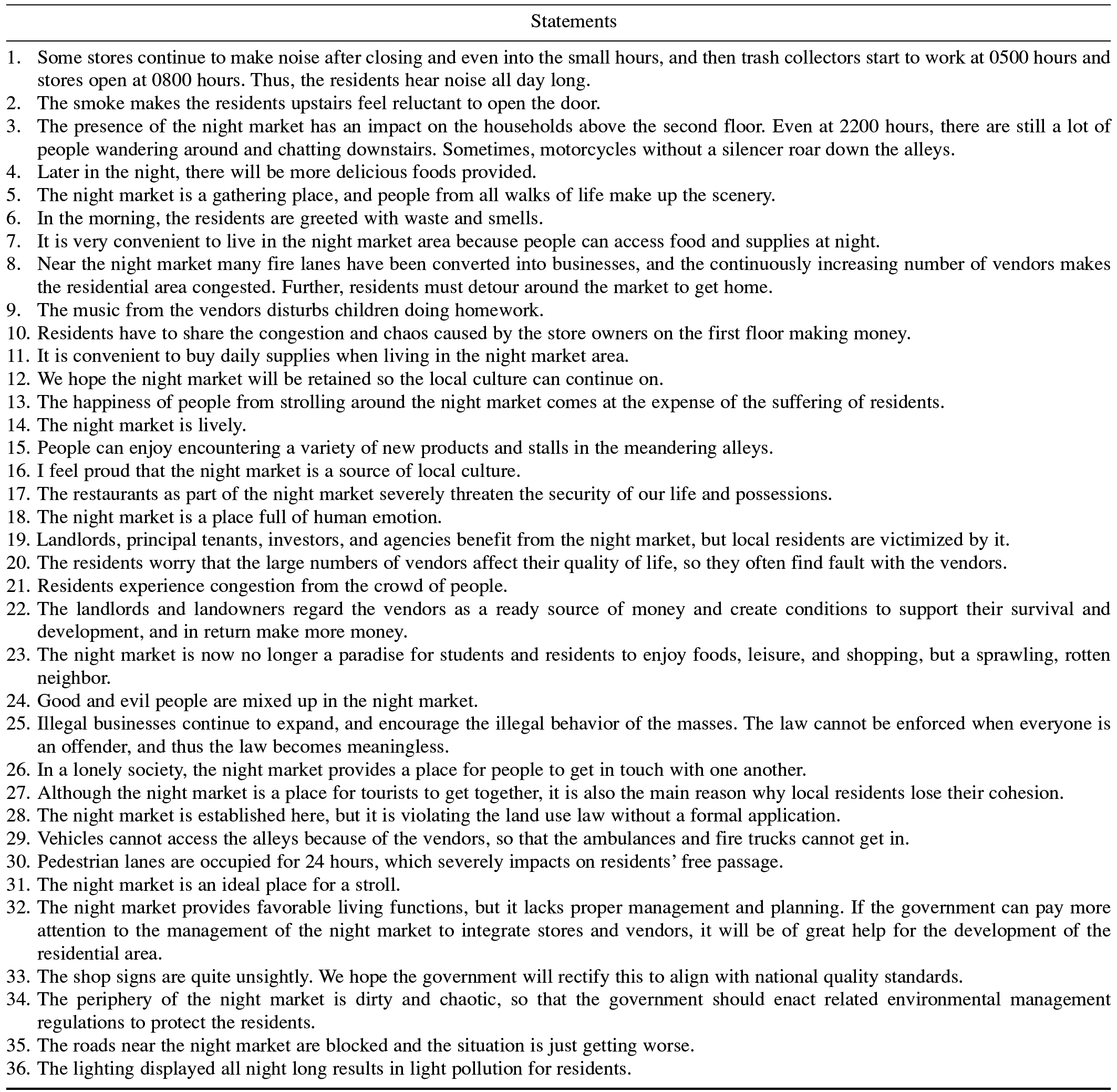

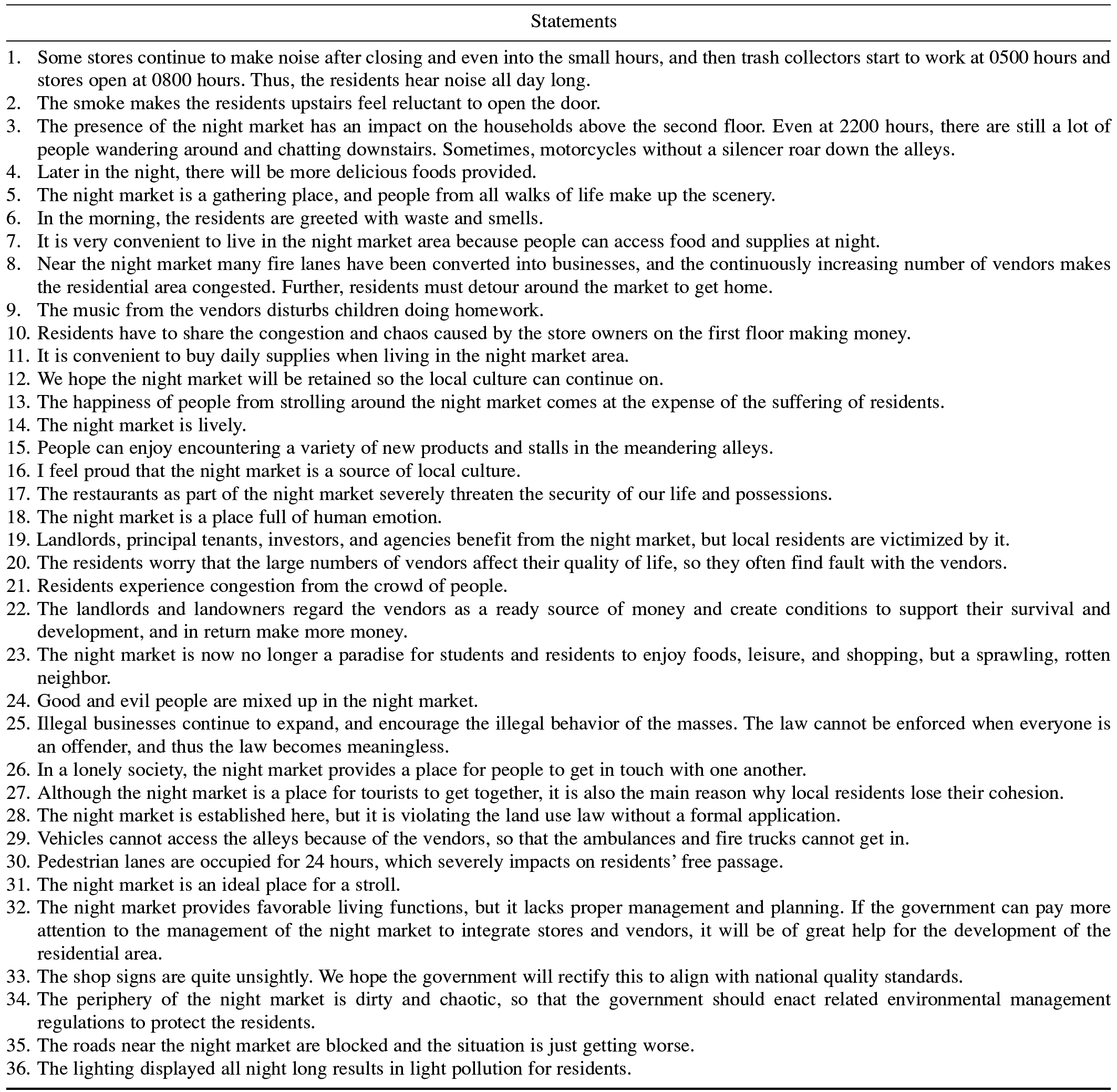

Development of Q concourse and Q set. The Q concourse refers to all opinions on the subject of the study. These were obtained from two sources: (a) interviews with participants, and (b) data from newspapers, magazines, periodicals, and books. Trained interviewers randomly contacted 29 residents on the street where the night market is located and asked them if they were willing to participate in a face-to-face interview that would take about 60 minutes. Their opinions were then combined with related content from magazines, reports, and weblog articles to complete a Q concourse, which was synthesized into 126 statements. We selected representative statements to form the Q set, using a deductive, structured method. We referred to Uysal et al.’s (2016) method to select statements in three categories of economy, society and culture, and environment. The statements were selected by three experts, two of whom were tourism impact researchers and the other a specialist in the Q method.

To finalize the content, validity, and index (CVI) of the statements, we adopted Paige and Morin’s (2016) practical steps. We used the two tourism activity experts’ CVI and the Q method expert’s CVI and advice to reduce the number of statements. Following Paige and Morin’s instructions, we deleted statements with a CVI score lower than .80. On the basis of the experts’ opinions we also added some new statements, then we referred to Ivlevs’ (2017) definition of statement selection, and developed a final set of 36 statements (see Table 1).

Table 1. The 36 Statements in the Q Set

P set (sample). This step is designed to identify the people who will be sorted into groups according to the Q set, and will form the P set. In general, the favored participants are those who can clearly express their opinions and ideas to solve the focal problem (Sexton, Snyder, Wadsworth, Jardine, & Ernest, 1998). A P set generally comprises 40 to 60 subjects in Q studies (Stainton Rogers, 1995). We used purposive sampling to identify participants who were representative of the residents’ views, including those living and working in the night market, those who were only living in the night market area, and landlords who had rental spaces in the night market area but did not live there.

The interviews were carried out from May 1 to June 30, 2015. Feng Chia night market in Taichung, Taiwan, was the investigation venue. In the P set process the interviewees were 50 residents of this night market, who were concerned about the effects of tourism on their community. The 29 residents who were interviewed at the Q concourse stage did not participate in the P set process, so that we could obtain more opinions in this stage. We contacted participants for the P set by ringing the doorbell of their home and asking if they were willing to take part in an interview. The interviews were conducted during the night market operation, from 5 pm to 12 am. Participants comprised 31 men and 19 women aged from 23 to 75 years, of whom 30 reported that they had been living in the night market area for more than 10 years, 10 for between 5 and 10 years, and 10 for less than 5 years.

Q-sorting. In this stage, participants took part in the Q-sorting of the Q set, to show if their ideas followed a normal distribution. They sorted the statements with which they strongly agreed (rightmost) and then those with which they strongly disagreed (leftmost), and finally sorted the statements for which they had no opinion (central position). When no further modifications needed to be made, the number of Q statements were written on the answer sheet, which completes a Q set. We also asked participants to identify the most significant statement for them, and explain why this was so. Finally, we asked them to provide demographic information comprising age, years of residence, if they worked in the night market, and if they owned a rental store.

Mathematical and explanatory analysis of Q-sorts. We used PQMethod 2.11 software to analyze the main factors of the night market that influenced residents’ QOL. The results of Q principal component analysis, which was used as the main method to extract common factors, showed that there were seven factors. However, to reduce the number of opinion groups, we used judgmental rotation to maximize the sum of sorts and minimize the number of groups (Eden, Donaldson, & Walker, 2005). Eden et al. (2005) proposed that determining the number of groups is a reflective process as it requires thinking about the groups that best fit the theory. Finally, we identified four opinion groups that accounted for 36 of 50 sorts (63% of the variance). These groups comprised 24 men and 12 women aged from 23 to 75 years, of whom 26 reported that they had been living in the night market area for more than 10 years, five for between 5 and 10 years, and five for less than 5 years.

Results

We classified the participants into four groups: Longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market; residents who live but do not work in the night market area and who feel that it is annoying and disturbing; residents who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors who are not as annoying as tourists, so these residents complain about the noisy night market but also enjoy the sound and sensory satisfaction it brings; and residents who have integrated the night market into their own life and have both positive and negative opinions about it, that is, they appreciate its benefits but desire further improvement and planning.

Longstanding Neighbors Who Love the Prosperity of the Night Market

The 23-person group of longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market, was the largest. Background analysis shows that the group had mostly been living in the night market area for more than 10 years, and the night market had blended well into their lives. These people either lived on the first floor, or did not live in the night market but had rental shops on the first floor or in the arcade. They stated that they cherish the convenience of living in the night market area and enjoy strolling around the night market for food and supplies (n = 7, z = 1.64). In addition, they considered that the night market is a good place for students and residents to enjoy food, leisure, and shopping (n = 23, z = -1.82). These people felt that the night market is a lively place, as the warm atmosphere brings care from families and greetings from friends (n = 14, z = 1.72). They did not believe there was any inconvenience, for example, the packed restaurants do not endanger people’s security (n = 17, z = -1.43). Although the market is open late into the night, visitors do not cause inconvenience to these residents (n = 13, z = -1.475). On the whole, they felt that the night market is not only closely related to Taiwanese people, but also represents a cultural treasure of Taiwan (n = 16, z = 1.83).

The market encompasses food, shopping, and entertainment, and provides access to local culture for this group whose views are represented by the following interviewee:

| The night market has a long history in Taiwan. The night market culture has been in people’s life for a long time, and strolling through the night market has long been an important public leisure activity. In the night market, you can feel the enthusiasm of the Taiwanese people. |

Residents Who Live but Do Not Work in the Night Market

Five people lived but did not work in the night market area and felt that it is annoying and disturbing. Background analysis shows that the majority of this group had been living there for more than 10 years. They lived above the second floor and did not have a store in the night market. We found that these residents’ QOL was seriously affected by the night market, especially the noise, because households above the second floor must deal with the impact of lower-level stores that are part of the night market. Even at 2200 hours, there are still a lot of people wandering around and chatting downstairs. Sometimes, motorcycles without silencers roar down the alleys (n = 3, z = 2.02). Some stores continue to make noise after closing and even into the small hours, and then trash collectors start work at 0500 hours and stores open at 0800 hours. Thus, the residents hear noise all day and all night (n = 1, z = 1.91). Another problem is that the roads are crammed with vendors and tourists. For example, the vendors occupy the roads to conduct business, which may hinder access by ambulances and fire trucks (n = 29, z = 1.39). In addition, residents dislike the congestion of the night market (n = 21, z = -2.16) because it brings discomfort (n = 31, z = -1.94). It is impossible for them to go for a walk because of the dense crowd and occupied roads (n = 29, z = 1.39). Such unconformable living experiences and congestion may occur because the night market was not included in the planning of the original residential area; thus, its presence makes the roads too narrow to walk on (n = 15, z = -1.42).

Overall, the group did not think that the night market could be compatible with a residential area. The group’s opinion is represented by the following statement:

| We accept the presence of the night market to offer the vendors a place to make a living, but people on the first floor focus on rent more than management, which is really a dilemma for us. |

Residents Who Dislike Tourists but Do Not Mind the Vendors

Background analysis shows that this five-person resident group who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors had been living in the night market area for less than 5 years. They lived above the second floor and did not work in the night market. Tourists have a negative impact on these residents’ QOL and are also the root cause of their opposition to the night market, because the happiness of the tourists comes at the expense of the suffering of the residents (n = 13, z = 2.06). Although they dislike tourists, they still have a good impression of the night market itself. For example, as they do not think that the noise disturbs their peace (n = 1, z = -2.08), or that the lighting all night long is light pollution (n = 36, z = -2.15), it is a good place for people to contact one another (n = 2, z = 1.03). Regarding vendors who also live in the night market, they think that vendors manage their delivery, cleaning, and closing times well (n = 1, z = -2.08). They do not think the presence of the night market is a hazard to the air quality (n = 2, z = -1.49). On the whole, these residents and the vendors mutually respect one another. For this reason, this group of residents hopes that government intervention (n = 34, z = 1.32) can give them and the vendors a better environment. Their opinions can be represented by the following participant:

| I have been working in the city for years. I choose to live in the night market area because the lively environment has eliminated my loneliness in the strange city. |

Residents Who Have Integrated the Night Market into Their Own Life

This group comprised three residents who have integrated the night market into their own life. According to background analysis, they have been living within the night market area, albeit outside the central part, for more than 10 years. They lived above the second floor and 67% of them worked in the night market. Although there are many vendors, their presence does not affect these residents’ QOL (n = 20, z = -1.66). The diversity of vendors provides a lot of functions in a food, leisure, and shopping environment (n = 23, z = -1.68), which facilitate the residents’ lives. In the night market the residents communicate with vendors who seem like neighbors (n = 23, z = -1.68). Although they have achieved a balance between the night market and their own life, they still expect some improvements in the night market. They hope that the government will pay more attention to improving the night market environment and integrate the stores and vendors (n = 32, z = 2.12) to improve the quality of the market and achieve unified governance. Specifically, they are most concerned about road management and wish the government would initiate institutional management to constrain the behavior of vendors to increase security. It is necessary to keep the road unblocked so that the ambulances and fire trucks can deal with emergencies in time. The blocked roads hinder this process and even lead to more serious damage (n = 29, z = 2.04). However, the crowded environment of the night market can be improved (n = 21, z = -1.69). Effective and unified management is not easy for residents, as this relies on government power to implement and ensure the residents have better QOL. The following statement is representative of the view of this group:

| My father’s generation settled here. I grew up here and enjoy the convenience that the night market brings to my life. But this does not mean that I do not see its shortcomings, so I still hope that the night market can be better, which cannot be realized without the intervention of public power. |

Overall, participants in three of the four groups thought that the night market has brought them problems; however, the problems are tolerable. Although some residents were accustomed to coexisting with the night market, as it still had advantages, they also hoped that the government would intervene and enact regulations to manage night markets so that they coexist better with local residents.

Discussion

Many empirical researchers have examined the impact of tourism activities on residents’ QOL (e.g., Naidoo & Sharpley, 2016; Okulicz-Kozaryn & Strzelecka, 2017; Rivera et al., 2016; Woo, Uysal, & Sirgy, 2018). In this study we focused on the impact of a night market on residents’ QOL, because as the impact of night (vs. day) tourism activities on residents’ lives is more significant, it is worth investigating how to reduce its negative effect.

That residents’ perceived QOL differed according to the number of years they had lived in the night market coincides with social disruption theory (Perdue, Long, & Kang, 1999). We found that residents who had lived in the night market for longer could better adapt to the problems brought by tourism activities. The residents in the two groups of longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market, and who have integrated the night market into their own life, had lived in the night market for more than 10 years, and their opinion of the impact of the market on their QOL was almost all positive. In comparison, residents in the group who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors had lived in the night market for a shorter period (less than 5 years), and their opinion on the impact of the market on their QOL was more negative. However, although the residents in the group who live but do not work in the night market had been living in the night market for more than 10 years, they responded that they had not obtained any benefit from the night market. Thus, social disruption theory cannot explain why they could not adapt to living in the night market. This indicates that the impact of the problems differs according to whether residents perceived that they had obtained benefits from the night market, and the actual benefits of the night market.

Regarding the three groups who responded that they had access to benefits, that is, the longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market, residents who have integrated the night market into their own life, and residents who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors, their QOL can be interpreted and their problems resolved from the balance of the costs and benefits brought by the presence of the market. Our results show that the longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market and residents who have integrated the night market into their own life had access to substantial benefits from the market. We can explore how tourism impacts on their QOL by using social exchange theory (Emerson, 1976) to assess the substantial benefits and costs from the night market. It has been pointed out in previous studies that researchers exploring the impact of tourism on residents’ QOL should examine the balance of substantial benefits and costs (Perdue et al., 1999).

However, residents who dislike tourists but do not mind the vendors perceived that they did not obtain substantial or tangible benefits from the night market; thus, the exchange benefit is an imaginary relationship link (i.e., a psychological benefit). Previous researchers have proposed that the entity relationship affects people’s attitude toward a residential area (Sampson, 1988, 1991). However, we detected that the light, sound, and people’s relationships in the night market made people feel less lonely, that is, the imaginary relationship link also affected their QOL. This may be because this link is a kind of alternative relationship through which residents with otherwise weak links to the entity can gain access to the city life. It seems that this group of people would like to break through the loneliness in the metropolis. Elias (1939/1991) stated that “it feels like there exists a wall between the ‘inherence’ of oneself and ‘the external world,’ and such emotion is true…on the other hand, it should be known that such emotion does not exist at the very beginning, but is the result from the concretization of the isolation action constructed by the society” (p. 125). It may be that the residents’ imaginary relationship with the night market plays such a role. This echoes Seijas’s (2017) viewpoint that an authentic nighttime atmosphere leads to a partial sense of belonging. Social exchange theory can, therefore, be used to explain psychological compensation in this group.

Social exchange theory cannot be used to explain the problems impacting on the QOL of the group of residents who live but do not work in the night market, because the focus in this theory is on how the benefits that the night market brings to residents can balance the costs. As these residents do not receive benefits from the night market, such an exchange does not exist. As a result, an explanatory theoretical base should be explored from the perspective of why the night market exists. As the night market began among disadvantaged groups during the social transformation of economic development in Taiwan (Yu, 1995), the presence of the market relies on the kindness of the residents, and it has the use benefit of providing poor people with a place to make a living (Yu, 1995). Therefore, it is important to enhance residents’ QOL through this use benefit. However, with the question of why residents have allowed the night market to be established (Yu, 1995), there is now a group who lives there, does not use the market, and who cannot coexist well with it. We think that empathy may be a breakthrough point in this regard, because many participants in our interviews talked about having empathy for the vendors. Moreover, the current situation for this group not receiving benefits from the market may have resulted from the interpersonal empathy gap that has arisen from the gradual individualization of Chinese society (Yan, 2009), that is, the residents are in a situation in which they cannot feel the feelings of others. An interpersonal empathy gap indicates either that community relations are weak (Yan, 2009) or that community social capital is gradually weakening (Putnam, 2000). This means that empathy is not easy to produce, especially regarding gains and losses (Fareri, Niznikiewicz, Lee, & Delgado, 2012). Fareri et al. (2012) pointed out that the gains and losses of intimate others (friends) are more likely to cause empathy, because people can easily put themselves in the same position as friends. However, as individuals become more concerned with themselves, their feelings of empathy are reduced (Yan, 2009). The weak neighborhood relationships in this focal night market community may be the reason why residents who live but do not work there and receive no benefits, can no longer tolerate the noise of the night market. Thus, it is necessary to upgrade the social capital of the night market community in ways that enhance networks within the community, such as hosting regular events and mutually beneficial activities to enhance interaction between residents with different perspectives, as well as shaping common memories, stories, and emotions through shared activities.

Regarding the opinion that the night market represents local culture, the residents in the group of longstanding neighbors who love the prosperity of the night market acknowledged that the market represents Taiwanese local culture and believed that the government should pay attention to this intangible property. The local cultural aspect was a key factor influencing their perceived QOL. However, these residents did not think that the current government intervention is sufficient, and called for the authorities to be more involved in the planning and control of the night market. Nevertheless, although government participation is very important (Boukas & Ziakas, 2016; Mason, 2003), the government should not modify local culture or eliminate what does not conform to the interests of tourism (Markwick, 2001). Such tourism development at the cost of local culture integrity will not bring long-term development and may even cause the residents and tourists to lose their recognition of such culture. As tourism development should maintain or revive the original culture, without selling an unreal tourism culture to visitors (Ahmad, 2013), it is very important to achieve a balance between the biases of this perspective (Taylor, 2001).

Previous researchers have found that the major problems affecting residents’ QOL comprise safety, noise, and traffic (Liang & Hui, 2016; Lin, Chen, & Filieri, 2017; Monterrubio, 2016). Although we also found these problems in varying degrees, there are some differences. The major difference in the impact of the nighttime economic activities on residents’ QOL (cf. Ngesan, 2014; Ngesan & Karim, 2012; Perdue et al., 1999) was that safety was not a major concern for the residents. This may be because Taiwan’s living safety is quite high by world standards. In other countries, for example, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, safety did influence residents’ QOL (Brands, van Aalst, & Schwanen, 2015).

Little research effort has been focused on developing a model to recover the basis of empathy so that residents can be encouraged to increase their tolerance for noise and inconvenient traffic. Future researchers could further explore the effect of increasing residents’ empathy on reducing their negative attitude toward nighttime tourism activities. In addition, the benefits often raised by past researchers relate to the actual sites at the night market. We have proposed the positive benefit to residents from the imaginary relationship link, which is like the temperature of a city. Future researchers could investigate this topic because promoting the advantages of this link may reduce the negative impact of nighttime activities on residents who have not fully integrated into the city. Further, future researchers could adopt the Q method using photographs to explore issues that cannot be understood through text alone, such as bias in participants’ feedback caused by wording (Magnini et al., 2012). Because the data we used were cross-sectional, the impact of future policy changes cannot be obtained. Future researchers could use longitudinal data to find how future government management policy changes would affect the QOL of residents in the night market area. Finally, although we identified the role of empathy with regard to use benefit, because of the differences between Eastern and Western cultures (Hofstede, 1983), future researchers could examine if empathy plays the same role in Western nighttime economic activities.

References

Ackerman, D., & Walker, K. (2012). Consumption of renao at a Taiwan night market. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 6, 209–222.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181211246366

Ahmad, A. (2013). The constraints of tourism development for a cultural heritage destination: The case of Kampong Ayer (Water Village) in Brunei Darussalam. Tourism Management Perspectives, 8, 106–113.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.09.002

Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50, 248–260.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32, 1056–1076.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

Bishop, R., & Robinson, L. S. (1999). Genealogies of exotic desire: The Thai night market in the Western imagination. In P. A. Jackson & N. M. Cook (Eds.), Genders and sexualities in modern Thailand (pp. 191–205). Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books.

Bolaños-Briceño, J. A., & Ariza-Marin, L. J. (2017). Nocturnity, 24-hours cities, and their socio-environmental effects [In Spanish]. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 27, 143–148.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v27n3.66450

Boukas, N., & Ziakas, V. (2016). Tourism policy and residents’ well-being in Cyprus: Opportunities and challenges for developing an inside-out destination management approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 44–54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.004

Brands, J., van Aalst, I., & Schwanen, T. (2015). Safety, surveillance and policing in the night-time economy: (Re)turning to numbers. Geoforum, 62, 24–37.

Chang, J., & Chiang, C. H. (2006). Segmenting American and Japanese tourists on novelty-seeking at night markets in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11, 391–406.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660600931242

Chatterton, P., & Hollands, R. (2002). Theorising urban playscapes: Producing, regulating and consuming youthful nightlife city spaces. Urban Studies, 39, 95–116.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220099096

Deery, M., Jago, L., & Fredline, L. (2012). Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tourism Management, 33, 64–73.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.026

Dennis, K. E., & Goldberg, A. P. (1996). Weight control self-efficacy types and transitions affect weight-loss outcomes in obese women. Addictive Behaviors, 21, 103–116.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(95)00042-9

Eden, S., Donaldson, A., & Walker, G. (2005). Structuring subjectivities? Using Q methodology in human geography. Area, 37, 413–422.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00641.x

Elias, N. (1991). The society of individuals (E. Jephcott, Trans.). New York, NY: Blackwell. (Original work published 1939).

Elliott, J. (1998). Tourism: Politics and public sector management. London, UK: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203416136

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

Fareri, D. S., Niznikiewicz, M. A., Lee, V. K., & Delgado, M. R. (2012). Social network modulation of reward-related signals. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 9045–9052.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0610-12.2012

Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 13, 46–74.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1983.11656358

Hollinshead, K. (2007). Indigenous Australia in the bittersweet world: The power of tourism in the projection of ‘old’ and ‘fresh’ visions of Aboriginality. In R. Butler & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications (pp. 281–304). Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-6446-2.50030-2

Hsu, Y.-J. (2013, April 11). 36 hours in Taipei, Taiwan. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://nyti.ms/3aEmfVe

Hunter, W. C. (2013). Understanding resident subjectivities toward tourism using Q method: Orchid Island, Taiwan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21, 331–354.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.685175

Ivlevs, A. (2017). Happy hosts? International tourist arrivals and residents’ subjective well-being in Europe. Journal of Travel Research, 56, 599–612.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516662353

Lee, S.-H., Chang, S.-C., Hou, J.-S., & Lin, C.-H. (2008). Night market experience and image of temporary residents and foreign visitors. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2, 217–233.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17506180810891591

Liang, Z.-X., & Hui, T.-K. (2016). Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tourism Development, 57, 56–67.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.001

Lin, Z., Chen, Y., & Filieri, R. (2017). Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tourism Management, 61, 436–442.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.02.013

Magnini, V. P., Ford, J. B., & LaTour, M. S. (2012). The role of qualitative methods in tourism QOL research: A critique and future agenda. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities (pp. 51–63). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2288-0_4

Markwick, M. C. (2001). Tourism and the development of handicraft production in the Maltese islands. Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 3, 29–51.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680010008694

Mason, P. (2003). Tourism impacts, planning and management. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Meister, E. (2011, April 8). Reveling in the real Taiwain [sic]. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/2R6xtdE

Monterrubio, C. (2016). The impact of spring break behaviour: An integrated threat theory analysis of residents’ prejudice. Tourism Management, 54, 418–427.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.004

Moscardo, G. (2009). Tourism and quality of life: Towards a more critical approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9, 159–170.

https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2009.6

Naidoo, P., & Sharpley, R. (2016). Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 16–25.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.002

Ngesan, M. R. (2014). Implication of nighttime leisure activities towards place identity of urban public park in Shah Alam and Putrajaya (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3aAx9LX

Ngesan, M. R., & Karim, H. A. (2012). Impact of night commercial activities towards quality of life of urban residents. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 35, 546–555.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.02.121

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., & Strzelecka, M. (2017). Happy tourists, unhappy locals. Social Indicators Research, 134, 789–804.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1436-9

Paige, J. B., & Morin, K. H. (2016). Q-sample construction: A critical step for a Q-methodological study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 96–110.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914545177

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Kang, Y. S. (1999). Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of Business Research, 44, 165–177.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00198-7

Pottie-Sherman, Y. (2013). Vancouver’s Chinatown night market: Gentrification and the perception of Chinatown as a form of revitalization. Built Environment, 39, 172–189.

https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.39.2.172

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rivera, M., Croes, R., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 5–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.002

Sampson, R. J. (1988). Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53, 766–779.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2095822

Sampson, R. J. (1991). Linking the micro- and macrolevel dimensions of community social organization. Social Forces, 70, 43–64.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/70.1.43

Seijas, A. (2017). Night studies [In Spanish]. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3gkxB39

Sexton, D., Snyder, P., Wadsworth, D., Jardine, A., & Ernest, J. (1998). Applying Q methodology to investigations of subjective judgments of early intervention effectiveness. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 95–107.

https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149801800205

Stainton Rogers, R. (1995). Q methodology. In J. A. Smith, R. Harré, & I. Van Longenhove (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology (pp. 178–193). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221792.n12

Taiwan Tourism Bureau. (2016). 2015 tourist spending and trends in Taiwan [In Chinese]. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2NP1AUX

Taylor, J. P. (2001). Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 28, 7–26.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00004-9

Uysal, M., Perdue, R., & Sirgy, M. J. (2012). Prologue: Tourism and quality-of-life (QOL) research: The missing links. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities (pp. 1–5). New York, NY: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2288-0_1

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. L. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Wijngaarden, V. (2017). Q method and ethnography in tourism research: Enhancing insights, comparability and reflexivity. Current Issues in Tourism, 20, 869–882.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1170771

Woo, E., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2018). Tourism impact and stakeholders’ quality of life. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42, 260–286.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016654971

Yan, Y. (2009). The individualization of Chinese society. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

Yu, S.-D. (1995). Meaning, disorder and the political economy of night markets in Taiwan (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of California, Davis, CA. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2R5r4iJ

Yu, S.-D. (2004). Hot and noisy: Taiwan’s night market culture. In D. K. Jordan, A. D. Morris, & M. L. Moskowitz (Eds.), The minor arts of daily life: Popular culture in Taiwan (pp. 129–149). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.

Ackerman, D., & Walker, K. (2012). Consumption of renao at a Taiwan night market. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 6, 209–222.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181211246366

Ahmad, A. (2013). The constraints of tourism development for a cultural heritage destination: The case of Kampong Ayer (Water Village) in Brunei Darussalam. Tourism Management Perspectives, 8, 106–113.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.09.002

Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50, 248–260.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32, 1056–1076.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

Bishop, R., & Robinson, L. S. (1999). Genealogies of exotic desire: The Thai night market in the Western imagination. In P. A. Jackson & N. M. Cook (Eds.), Genders and sexualities in modern Thailand (pp. 191–205). Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books.

Bolaños-Briceño, J. A., & Ariza-Marin, L. J. (2017). Nocturnity, 24-hours cities, and their socio-environmental effects [In Spanish]. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 27, 143–148.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v27n3.66450

Boukas, N., & Ziakas, V. (2016). Tourism policy and residents’ well-being in Cyprus: Opportunities and challenges for developing an inside-out destination management approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 44–54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.004

Brands, J., van Aalst, I., & Schwanen, T. (2015). Safety, surveillance and policing in the night-time economy: (Re)turning to numbers. Geoforum, 62, 24–37.

Chang, J., & Chiang, C. H. (2006). Segmenting American and Japanese tourists on novelty-seeking at night markets in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11, 391–406.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660600931242

Chatterton, P., & Hollands, R. (2002). Theorising urban playscapes: Producing, regulating and consuming youthful nightlife city spaces. Urban Studies, 39, 95–116.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220099096

Deery, M., Jago, L., & Fredline, L. (2012). Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tourism Management, 33, 64–73.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.026

Dennis, K. E., & Goldberg, A. P. (1996). Weight control self-efficacy types and transitions affect weight-loss outcomes in obese women. Addictive Behaviors, 21, 103–116.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(95)00042-9

Eden, S., Donaldson, A., & Walker, G. (2005). Structuring subjectivities? Using Q methodology in human geography. Area, 37, 413–422.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00641.x

Elias, N. (1991). The society of individuals (E. Jephcott, Trans.). New York, NY: Blackwell. (Original work published 1939).

Elliott, J. (1998). Tourism: Politics and public sector management. London, UK: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203416136

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

Fareri, D. S., Niznikiewicz, M. A., Lee, V. K., & Delgado, M. R. (2012). Social network modulation of reward-related signals. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 9045–9052.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0610-12.2012

Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 13, 46–74.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1983.11656358

Hollinshead, K. (2007). Indigenous Australia in the bittersweet world: The power of tourism in the projection of ‘old’ and ‘fresh’ visions of Aboriginality. In R. Butler & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications (pp. 281–304). Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-6446-2.50030-2

Hsu, Y.-J. (2013, April 11). 36 hours in Taipei, Taiwan. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://nyti.ms/3aEmfVe

Hunter, W. C. (2013). Understanding resident subjectivities toward tourism using Q method: Orchid Island, Taiwan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21, 331–354.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.685175

Ivlevs, A. (2017). Happy hosts? International tourist arrivals and residents’ subjective well-being in Europe. Journal of Travel Research, 56, 599–612.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516662353

Lee, S.-H., Chang, S.-C., Hou, J.-S., & Lin, C.-H. (2008). Night market experience and image of temporary residents and foreign visitors. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2, 217–233.

https://doi.org/10.1108/17506180810891591

Liang, Z.-X., & Hui, T.-K. (2016). Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tourism Development, 57, 56–67.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.001

Lin, Z., Chen, Y., & Filieri, R. (2017). Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tourism Management, 61, 436–442.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.02.013

Magnini, V. P., Ford, J. B., & LaTour, M. S. (2012). The role of qualitative methods in tourism QOL research: A critique and future agenda. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities (pp. 51–63). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2288-0_4

Markwick, M. C. (2001). Tourism and the development of handicraft production in the Maltese islands. Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 3, 29–51.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680010008694

Mason, P. (2003). Tourism impacts, planning and management. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Meister, E. (2011, April 8). Reveling in the real Taiwain [sic]. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/2R6xtdE

Monterrubio, C. (2016). The impact of spring break behaviour: An integrated threat theory analysis of residents’ prejudice. Tourism Management, 54, 418–427.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.004

Moscardo, G. (2009). Tourism and quality of life: Towards a more critical approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9, 159–170.

https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2009.6

Naidoo, P., & Sharpley, R. (2016). Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 16–25.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.002

Ngesan, M. R. (2014). Implication of nighttime leisure activities towards place identity of urban public park in Shah Alam and Putrajaya (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3aAx9LX

Ngesan, M. R., & Karim, H. A. (2012). Impact of night commercial activities towards quality of life of urban residents. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 35, 546–555.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.02.121

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., & Strzelecka, M. (2017). Happy tourists, unhappy locals. Social Indicators Research, 134, 789–804.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1436-9

Paige, J. B., & Morin, K. H. (2016). Q-sample construction: A critical step for a Q-methodological study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 96–110.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914545177

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Kang, Y. S. (1999). Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of Business Research, 44, 165–177.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00198-7

Pottie-Sherman, Y. (2013). Vancouver’s Chinatown night market: Gentrification and the perception of Chinatown as a form of revitalization. Built Environment, 39, 172–189.

https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.39.2.172

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rivera, M., Croes, R., & Lee, S. H. (2016). Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 5–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.002

Sampson, R. J. (1988). Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53, 766–779.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2095822

Sampson, R. J. (1991). Linking the micro- and macrolevel dimensions of community social organization. Social Forces, 70, 43–64.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/70.1.43

Seijas, A. (2017). Night studies [In Spanish]. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3gkxB39

Sexton, D., Snyder, P., Wadsworth, D., Jardine, A., & Ernest, J. (1998). Applying Q methodology to investigations of subjective judgments of early intervention effectiveness. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 95–107.

https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149801800205

Stainton Rogers, R. (1995). Q methodology. In J. A. Smith, R. Harré, & I. Van Longenhove (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology (pp. 178–193). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221792.n12

Taiwan Tourism Bureau. (2016). 2015 tourist spending and trends in Taiwan [In Chinese]. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2NP1AUX

Taylor, J. P. (2001). Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 28, 7–26.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00004-9

Uysal, M., Perdue, R., & Sirgy, M. J. (2012). Prologue: Tourism and quality-of-life (QOL) research: The missing links. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities (pp. 1–5). New York, NY: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2288-0_1

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. L. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Wijngaarden, V. (2017). Q method and ethnography in tourism research: Enhancing insights, comparability and reflexivity. Current Issues in Tourism, 20, 869–882.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1170771

Woo, E., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2018). Tourism impact and stakeholders’ quality of life. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42, 260–286.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016654971

Yan, Y. (2009). The individualization of Chinese society. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

Yu, S.-D. (1995). Meaning, disorder and the political economy of night markets in Taiwan (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of California, Davis, CA. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2R5r4iJ

Yu, S.-D. (2004). Hot and noisy: Taiwan’s night market culture. In D. K. Jordan, A. D. Morris, & M. L. Moskowitz (Eds.), The minor arts of daily life: Popular culture in Taiwan (pp. 129–149). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.

Table 1. The 36 Statements in the Q Set

Hao-Kai Hung, Department of Business Administration, Yango University, No. 99 Denglong Road, Wolong Mountain, Fuzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone, Mawei, Fujian 350015, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]