The differential effects of facial expressions on behavior: Conscious and automatic processing

Main Article Content

Cite this article:

Wang, H.,

Yue, T.,

Luo, H.,

Li, Z., &

Hu, D.

(2026). The differential effects of facial expressions on behavior: Conscious and automatic processing.

Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal,

54(1),

e15208.

Abstract

Full Text

References

Tables and Figures

Acknowledgments

Author Contact

Emotional information helps human beings produce corresponding behavioral responses, namely, approach and avoidance. However, it remains unclear whether emotion can activate approach and avoidance responses at both conscious and automatic processing levels. We conducted two experiments to compare the impact of happy, sad, and fearful faces on behavior (assessed using a joystick task) and found that happiness was associated with approach and fear with avoidance, regardless of whether emotional expressions were evaluated consciously or processed automatically (assessed via a gender judgment task). However, sad faces elicited approach responses at the conscious processing level, but no significant tendency emerged when conscious evaluation was reduced. Thus, facial emotional expressions can trigger approach–avoidance tendencies at both conscious and automatic processing levels. However, the specific patterns of these effects vary, suggesting that the underlying mechanisms may operate differently. Implications of the findings are discussed.

The ability to interpret facial expressions is critical for survival, reproduction, and social functioning (Barrett et al., 2019; Johnson, 2021). It enables rapid identification of environmental threats and supports emotional communication within social groups (Lang et al., 1990; Neumann & Strack, 2000). Approach–avoidance decisions are fundamental for survival: avoiding negative stimuli (e.g., predators) reduces threats, while approaching positive stimuli (e.g., food) enhances survival and reproductive success (Neumann & Strack, 2000). These behaviors are linked to the motivational system, which evaluates contextual risks and guides appropriate actions (Bamford & Ward, 2008) through two pathways: appetitive (approach) and aversive (avoidance; Cacioppo et al., 1997).

Previous research has consistently shown that emotional stimuli elicit compatible approach or avoidance responses: positive stimuli promote approach and negative stimuli promote avoidance (Bamford & Ward, 2008; Chen & Bargh, 1999; Neumann & Strack, 2000). However, the mechanisms underlying this link remain debated. Motivational orientation theory posits that valence-driven responses occur automatically (Chen & Bargh, 1999), while event coding theory suggests compatibility effects arise from conscious valence evaluation (Hommel et al., 2001). For example, Rotteveel and Phaf (2004) found no compatibility effects during a gender judgment task, and reported the disappearance of affective compatibility for task-irrelevant valences. The key controversy is whether emotions can automatically activate behavioral reactions, independent of explicit evaluation. Some researchers have proposed that these mechanisms may operate independently or in parallel (Kozlik et al., 2015; Krieglmeyer et al., 2010). However, testing this assumption requires resolving whether the affect–behavior link exists at both explicit and implicit levels (McGrew, 2022), and whether affective information has different influences on behavioral tendencies at these levels (Wang et al., 2023).

Affect can be processed automatically (Carr et al., 2003; Morelli et al., 2015) and is closely linked to approach–avoidance motivation (Aupperle & Paulus, 2010). Differences in the affect–behavior link may result from variations in experimental apparatus (joystick vs. vertical stand), reference frames (self vs. object), and stimulus type (facial expressions vs. words; Ascheid et al., 2019; Fricke & Vogel, 2020; Wittekind et al., 2021). Approach–avoidance behaviors are typically horizontal (Hoofs et al., 2019), so joysticks are more appropriate for representing these tendencies. A self-referential frame, such as pulling or pushing, better reflects the relationship between affect and behavior. In this study we used arm flexion and extension via a joystick task to test if emotional expressions activated approach and avoidance responses at both conscious and automatic levels.

The affect–behavior link may arise from a match between emotional valence and evaluative coding of approach–avoidance behaviors, while motivational orientation theory suggests that valence stimuli automatically activate corresponding systems (Kuhl et al., 2021). Motivational orientation theory supports the idea that emotional stimuli can directly influence approach–avoidance responses without the need for conscious evaluation (Chen & Bargh, 1999). Conversely, event coding theory suggests that these responses may depend on the compatibility between emotional valence and evaluative movement coding, leading to different behavioral effects under conscious and automatic processing conditions (Hommel et al., 2001). Previous studies have shown that emotional stimuli typically facilitate approach or avoidance behavior (Bamford & Ward, 2008; Neumann & Strack, 2000), but these effects may not hold under implicit conditions, particularly for task-irrelevant emotional valences (Rotteveel & Phaf, 2004).

Given this theoretical background, we anticipated that happy faces would trigger approach behavior at both processing levels, fearful faces would trigger avoidance behavior at both levels, and sad faces would trigger approach behavior only at the conscious level, with no significant effects being observed at the automatic level. Thus, we designed two experiments, the first of which entailed an emotional judgment task for conscious processing and the second focused on gender discrimination for automatic processing. We measured approach and avoidance behaviors through arm flexion and extension and compared the effects of happy, sad, and fearful faces at both processing levels.

Experiment 1

Method

Design

To balance reaction times for pull and push movements, we paired happy, sad, and fearful faces with neutral faces. Experiment 1 used a 2 (picture category: emotional vs. neutral) × 2 (lever direction: push vs. pull) repeated-measures design, with the condition order randomized across participants. Participants were instructed to move the joystick as quickly as possible in the specified direction.

Participants

We recruited 52 right-handed undergraduates (35 women, 17 men; Mage = 21.50 years, SD = 1.60, range = 19–26) from Southwest University via advertisements. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Scientific Research School of Educational Sciences at Chongqing Normal University. All participants provided informed consent.

Materials

Stimuli included 32 color pictures from the Chinese Affective Picture System (Lu et al., 2005), with eight stimuli per condition (happy, sad, fear, neutral). The pictures’ valence differed significantly across each emotional condition, except for sadness and fear, Mhappiness = 6.61, Msadness = 2.65, Mfear = 2.62, Mneutral = 4.25; F(3, 31) = 169.03, MSE = 28.30, p < .001. Arousal values for happy, sad, and fearful faces were all higher than those for neutral faces, with the three emotional conditions matched with one another, Mhappiness = 7.13, Msadness = 6.96, Mfear = 7.08, Mneutral = 3.96; F(3, 31) = 18.36, MSE = 19.25, p < .001. All images were standardized (15 cm × 10 cm, 100 pixels per inch).

Instruments

A joystick (PXN-2103, Litestar) connected to a computer via USB was used to measure arm flexion and extension. Reaction times were recorded using E-Prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The computer screen resolution was 640 × 480 pixels and the middle of the longitudinal axis served as the baseline position. The joystick was placed on a rubber pad and participants were instructed to maintain a consistent grip.

Procedure

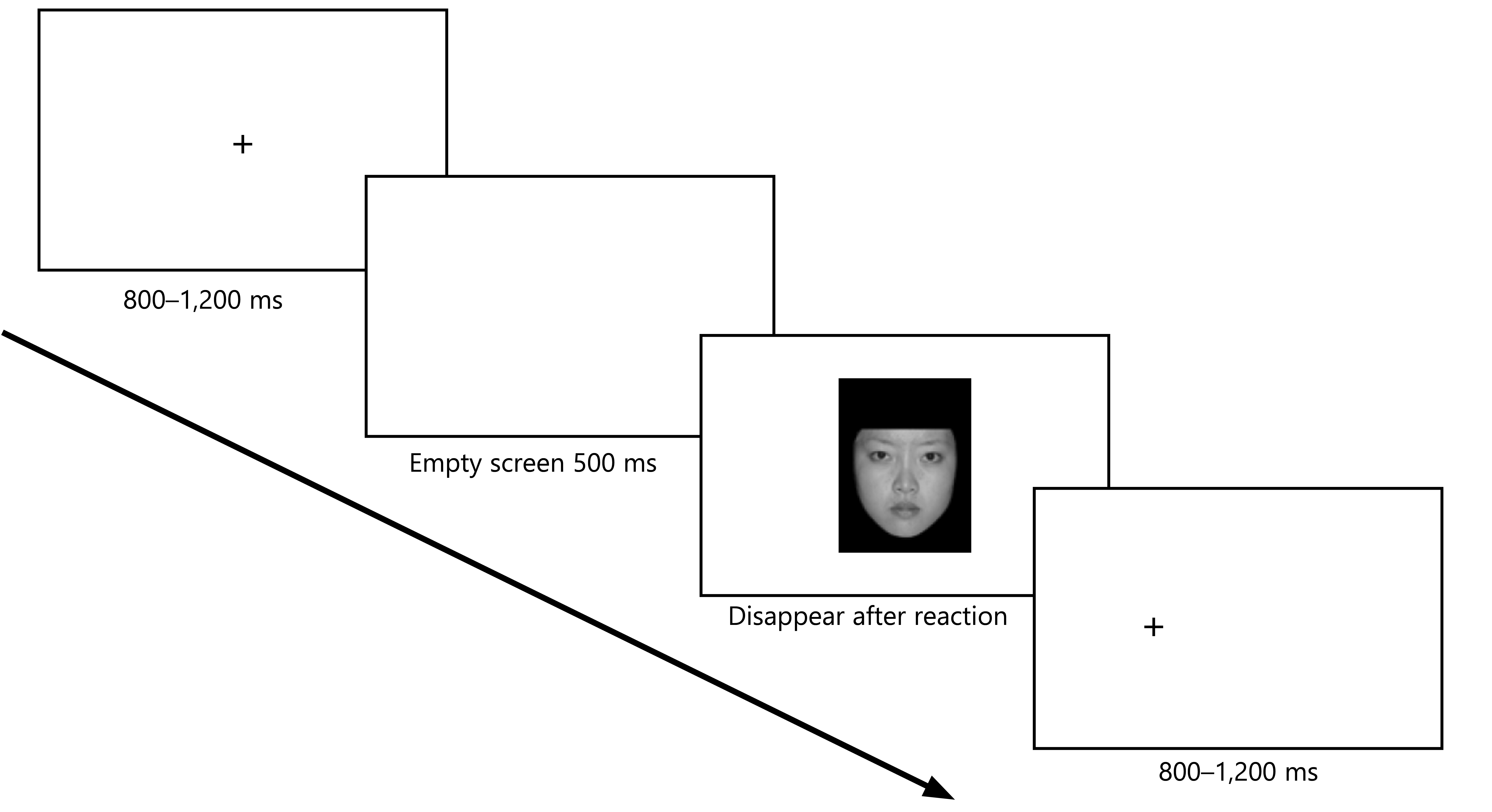

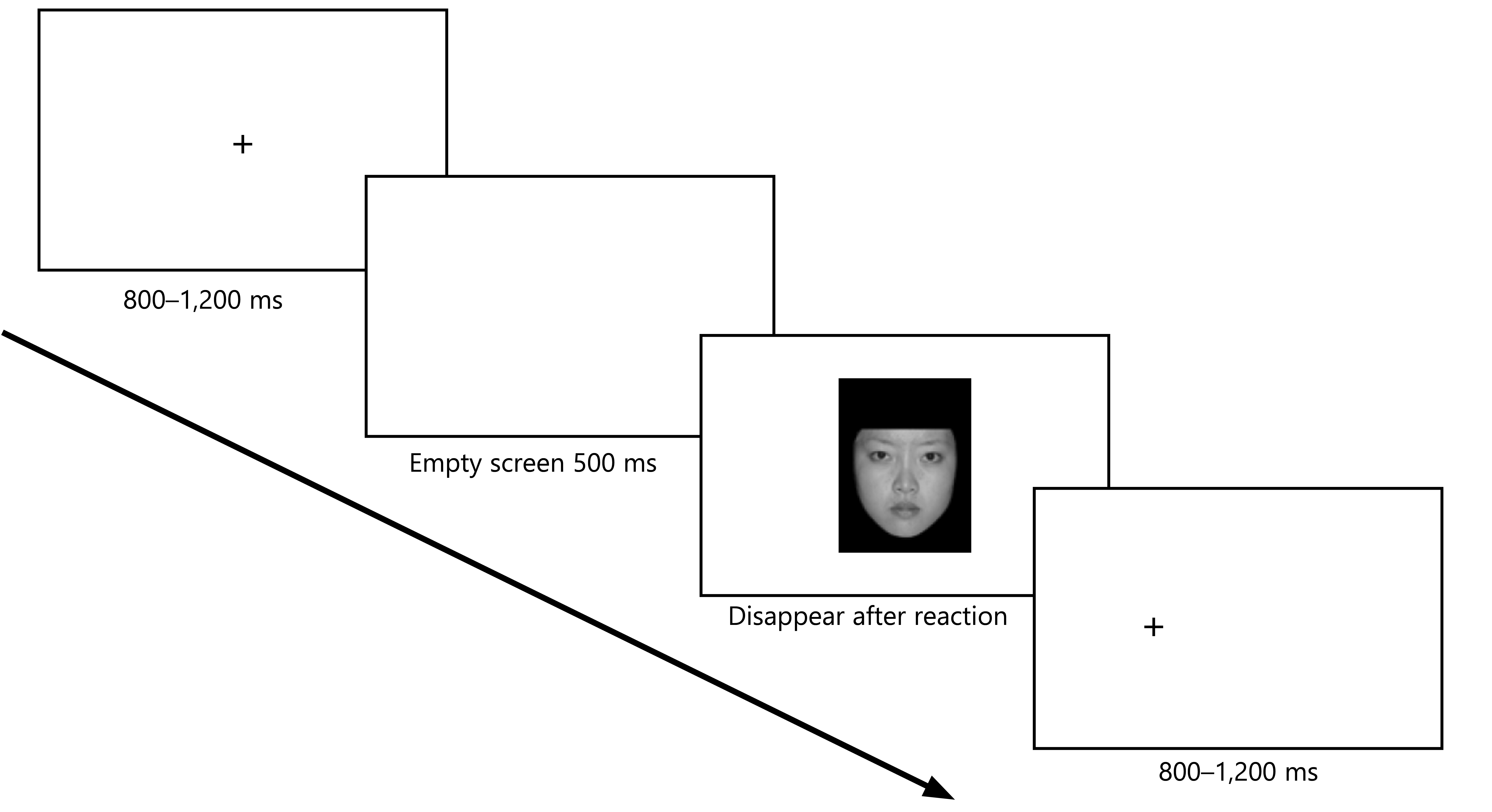

Each condition consisted of two blocks, with 16 randomly presented trials per block (eight emotional and eight neutral faces). In one block, participants pulled the joystick for emotional faces and pushed the joystick for neutral; in the other, the actions were reversed. Participants practiced before the experiment. Trials began with a red fixation cross (“+”) presented for 800–1,200 ms, followed by a blank screen for 500 ms, then the stimulus. Participants were instructed to pull or push the joystick lever as quickly as possible based on the task instructions. If no response was made, the stimulus disappeared automatically after 2,000 ms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Experiment Workflow

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 to conduct a 2 (category of picture: emotional vs. neutral) × 2 (lever direction: push vs. pull) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the mean reaction times.

Results

Lever Direction

Significant effects were found for both happiness, F(1, 51) = 16.48, MSE = 1396.73, p < .001, η2 = .24, and sadness, F(1, 51) = 14.60, MSE = 1188.49, p < .001, η2 = .22, but not fear.

Emotional Expression

Significant effects were observed for happiness, F(1, 51) = 77.52, MSE = 946.23, p < .001, η2 = .60; sadness, F(1, 51) = 61.97, MSE = 2428.15, p < .001, η2 = .55; and fear, F(1, 51) = 159.63, MSE = 1346.70, p < .001, η2 = .76.

Interaction Effect

Trends for emotional expression × lever direction were found for happiness, F(1, 51) = 4.61, MSE = 2454.25, p < .05, η2 = .08; sadness, F(1, 51) = 5.38, MSE = 2154.64, p < .05, η2 = .10; and fear, F(1, 51) = 10.30, MSE = 1346.06, p < .01, η2 = .17.

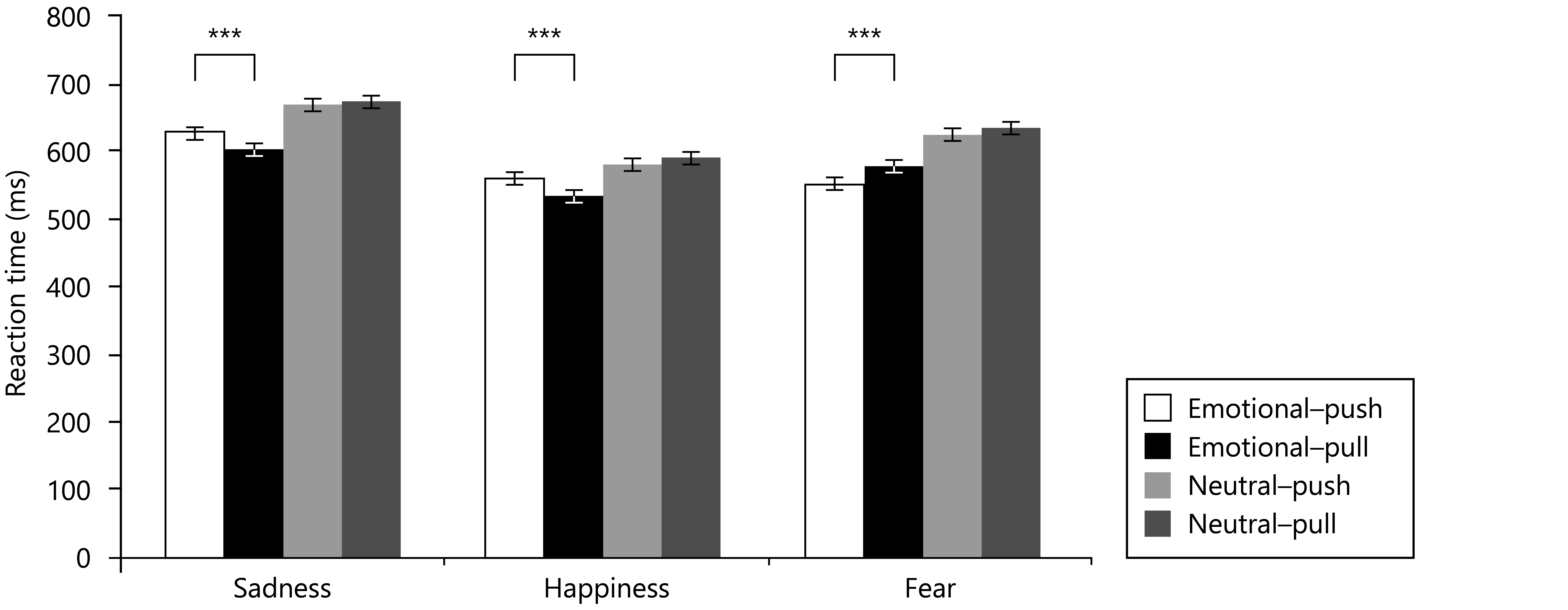

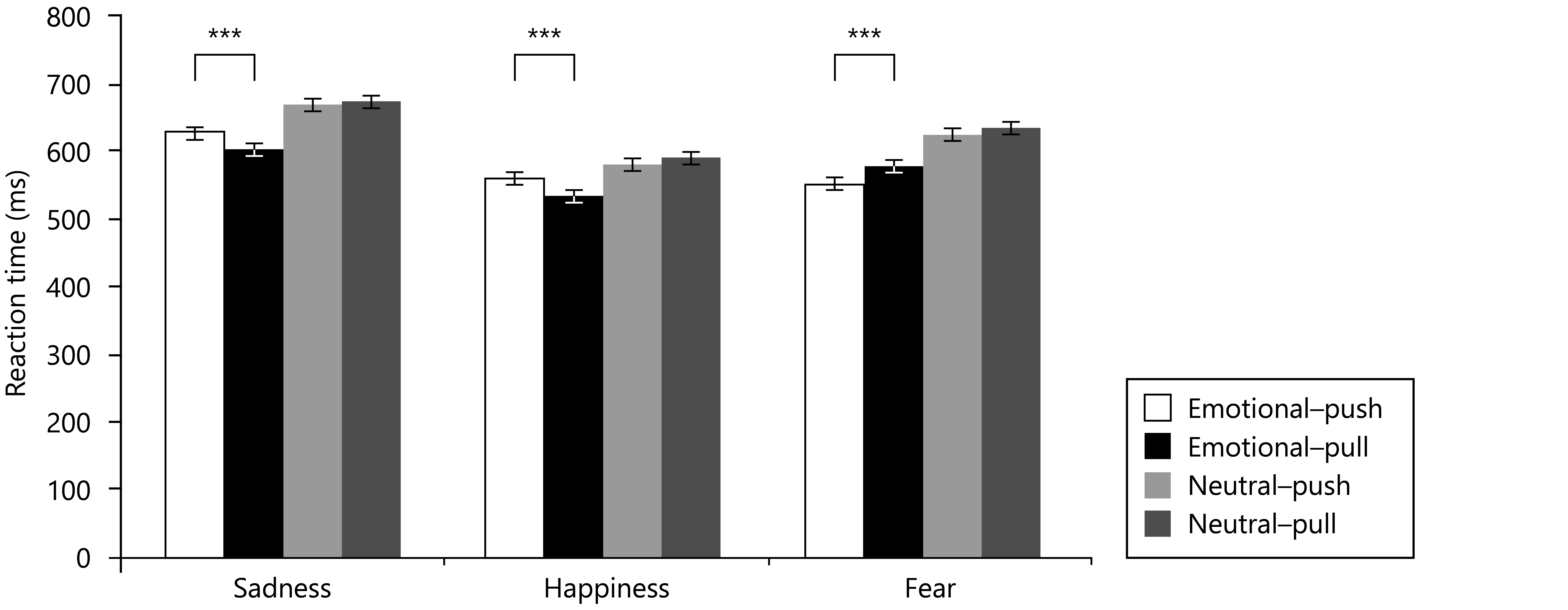

A simple effects analysis of the three conditions showed that pulling was faster than pushing for happy expressions, F(1, 51) = 19.54, MSE = 1703.69, p < .001, η2 = .28, and sad expressions, F(1, 51) = 13.41, MSE = 2136.82, p < .001, η2 = .21, indicating approach responses. Fearful expressions elicited avoidance, with faster pushing than pulling, F(1, 51) = 13.36, MSE = 954.94, p < .001, η2 = .21. No significant effects were found for neutral faces, indicating no systematic response time differences (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Push–Pull Reaction Time Results for Experiment 1

Note. *** p < .001.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 examined how facial emotional expressions influence behavioral tendencies through affective evaluation tasks. However, affective processing can also occur automatically, without conscious awareness (Dimberg et al., 2000; Duckworth et al., 2002; Whalen et al., 2001). Questions regarding whether facial emotional expressions can activate behavioral reactions without explicit emotional evaluation, and whether such reactions differ, were beyond the scope of Experiment 1.

Therefore, in Experiment 2 participants categorized the gender of emotional faces, allowing for the processing of emotional expressions without conscious evaluation (Morris et al., 1998). We expected that emotional expressions would automatically influence arm flexion and extension, although the observed patterns might differ from Experiment 1.

Method

Design

Participants were instructed to categorize the gender of emotional faces while disregarding their emotional content, inducing automatic processing of emotional information. The experiment had a 4 (emotional expression: happiness vs. sadness vs. fear vs. neutral) × 2 (action: flexion vs. extension) within-subjects factorial design.

Participants

We recruited 41 right-handed undergraduates (22 women, 19 men; Mage = 21.85 years, SD = 1.67, range = 18–25) from Southwest University as participants, following the same procedure as Experiment 1. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research School of Educational Sciences at Chongqing Normal University. All participants provided informed consent.

Materials and Instruments

We used the same stimuli and joystick setup as Experiment 1.

Procedure

Participants completed two blocks of 32 randomly presented trials each (eight per emotional condition). In one block, participants pulled for female faces and pushed for male faces; in the other, the actions were reversed. The trial procedure mirrored Experiment 1, except for the task instructions.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 to conduct a 4 (emotional expression: happiness vs. sadness vs. fear vs. neutral) × 2 (action: flexion vs. extension) repeated-measures ANOVA of the mean reaction times.

Results

Lever Direction

There was no main effect of lever direction.

Emotional Expression

The main effect of the category of expression was significant, F(3, 120) = 7.25, MSE = 1272.60, p < .001, η2 = .15.

Interaction Effect

There was a significant interaction between emotional expression and lever direction, F(3, 120) = 3.85, MSE = 1122.63, p < .001, η2 = .09, indicating differential directions for the polar emotions.

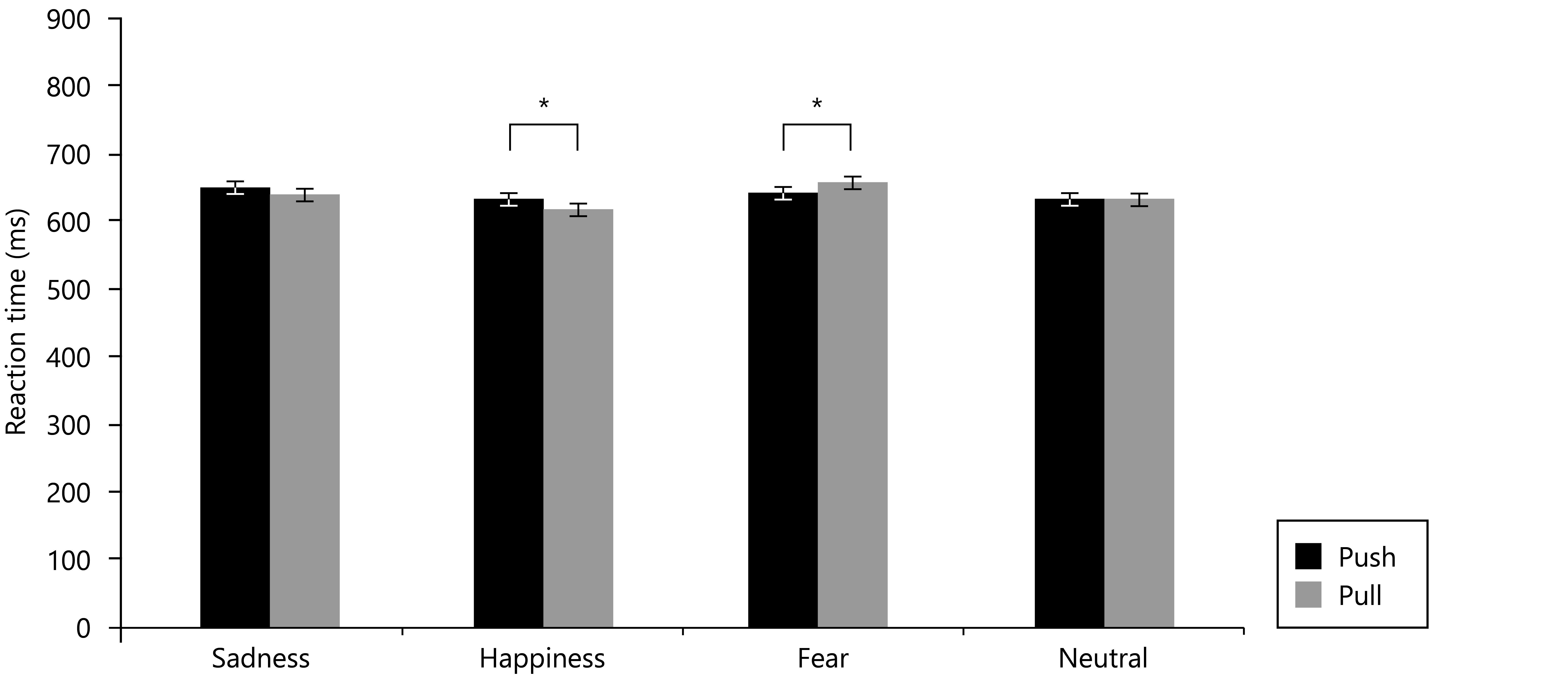

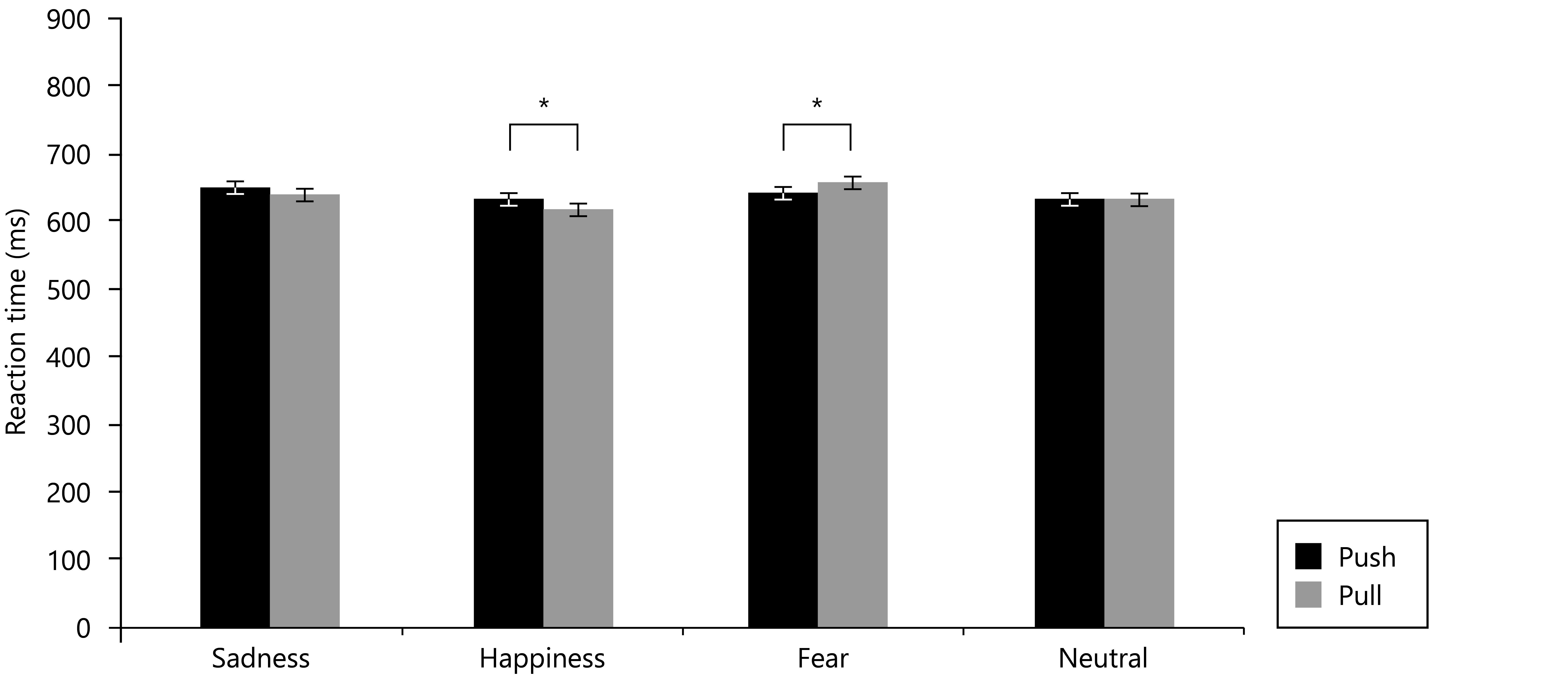

A simple effects analysis showed no differences in response to either sad or neutral faces, whereas pulling was faster than pushing with happy faces, F(1, 40) = 6.52, MSE = 578.99, p < .05, η2 = .14. In response to the fearful face, pushing was faster than pulling, F(1, 40) = 4.93, MSE = 1338.82, p < .05, η2 = .11 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Push–Pull Reaction Time Results for Experiment 2

Note. * p < .05.

Happy and fearful faces elicited approach and avoidance responses, respectively, even under automatic processing. Sad faces showed no significant influence, suggesting context-dependent or complex mechanisms for sadness in automatic processing.

General Discussion

In summary, our findings revealed that facial emotional expressions influenced behavioral tendencies through distinct mechanisms at conscious and automatic processing levels. Experiment 1 revealed that under conscious evaluation, happy and sad faces elicited approach responses, while fear elicited avoidance. Experiment 2 showed that happiness and fear produced consistent effects at the automatic level, but sadness had no significant influence. Thus, the effects of happiness and fear were consistent across both processing levels, while sadness showed a unique pattern, suggesting that its influence may be dependent on context or mediated by social learning processes. These results not only replicate previous research (Krieglmeyer et al., 2010; Neumann & Strack, 2000; Paulus & Wentura, 2016) but also contribute to understanding of how emotional information shapes behavior, emphasizing the interplay between emotional labels, valence, and survival value in different processing contexts.

Rotteveel and Phaf (2004) found no significant effect of emotional faces on avoidance behavior at the automatic processing level, potentially due to task design limitations. Their use of up/down arm movements failed to capture the spatial and representational distance changes inherent in approach–avoidance behaviors. In contrast, push/pull movements better reflect these tendencies, as they involve both spatial and emotional attributes (Shoumy et al., 2020). This distinction highlights the importance of task design in studying automatic emotional processing.

The approach behavior triggered by sadness aligns with Seidel et al.’s (2010) explanation of an automatic tendency to support others in distress. This supports event coding theory, which posits that approach–avoidance responses are guided by the stimulus’s label (e.g., “help” for sadness) rather than its valence (Eder & Rothermund, 2008; Hommel et al., 2001). The approach–avoidance labels for happiness and fear align with their valence (reward and threat, respectively), whereas sadness, although negative, may carry an approach label due to its association with helping behavior (Arias et al., 2020). This highlights the role of emotional labels in shaping behavior, independent of valence.

At the automatic processing level, the consistent effects of happiness and fear indicated that emotional faces can influence approach–avoidance responses without conscious interpretation. According to motivational orientation theory (Strack & Deutsch, 2004), positive and negative stimuli automatically activate compatible motivations, likely due to their survival and reproductive advantages. The lack of a significant effect for sadness in our experiments may reflect its lower survival value compared to happiness (reward) and fear (threat). This suggests that the survival value and valence of emotions significantly shape the direction of behavioral responses.

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations should be noted. First, we did not analyze the gender of the stimuli in Experiment 2. Future studies could explore whether gender influences behavioral tendencies. Second, our focus on facial expressions limits the generalizability of the findings; future research could replicate these studies with emotional words or sentences to test the robustness of our conclusions. Future research could also explore the neural mechanisms underlying approach–avoidance effects, as well as investigating how individual differences, such as personality traits or cultural background, might moderate the observed patterns. Additionally, applying these findings to real-world scenarios, such as social interactions or marketing strategies, could provide valuable insights into how emotional expressions influence human behavior in practical settings.

Conclusion

Our research has demonstrated that facial emotional expressions can trigger approach–avoidance tendencies at both conscious and automatic levels. However, the mechanisms underlying these effects may differ between the two processing modes. At the conscious level, behavioral tendencies are primarily shaped by the approach–avoidance label associated with the emotion. In contrast, at the automatic level, effects may depend on the survival value of the emotion, with valence influencing the direction of these effects.

References

Arias, J. A., Williams, C., Raghvani, R., Aghajani, M., Baez, S., Belzung, C., Booij, L., Busatto, G., Chiarella, J., Fu, C. H., Ibanez, A., Liddell, B. J., Lowe, L., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Rosa, P., & Kemp, A. H. (2020). The neuroscience of sadness: A multidisciplinary synthesis and collaborative review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 111, 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.006

Ascheid, S., Wessa, M., & Linke, J. O. (2019). Effects of valence and arousal on implicit approach/avoidance tendencies: A fMRI study. Neuropsychologia, 131, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.05.028

Aupperle, R. L., & Paulus, M. P. (2010). Neural systems underlying approach and avoidance in anxiety disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/raupperle

Bamford, S., & Ward, R. (2008). Predispositions to approach and avoid are contextually sensitive and goal dependent. Emotion, 8(2), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.174

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1), 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930

Cacioppo, J. T., Gardner, W. L., & Berntson, G. G. (1997). Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: The case of attitudes and evaluative space. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0101_2

Carr, L., Iacoboni, M., Dubeau, M.-C., Mazziotta, J. C., & Lenzi, G. L. (2003). Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: A relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(9), 5497–5502. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0935845100

Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(2), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025002007

Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M., & Elmehed, K. (2000). Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions. Psychological Science, 11(1), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00221

Duckworth, K. L., Bargh, J. A., Garcia, M., & Chaiken, S. (2002). The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychological Science, 13(6), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00490

Eder, A. B., & Rothermund, K. (2008). When do motor behaviors (mis)match affective stimuli? An evaluative coding view of approach and avoidance reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 137(2), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.262

Fricke, K., & Vogel, S. (2020). How interindividual differences shape approach-avoidance behavior: Relating self-report and diagnostic measures of interindividual differences to behavioral measurements of approach and avoidance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 111, 30–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.008

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). Codes and their vicissitudes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(5), 910–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X01520105

Hoofs, V., Boehler, C. N., & Krebs, R. M. (2019). Biasing actions by incentive valence in an approach/avoidance task. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1), Article 42. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.205

Johnson, E. (2021). Face validity. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (pp. 1957–1957). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91280-6_308

Kozlik, J., Neumann, R., & Lozo, L. (2015). Contrasting motivational orientation and evaluative coding accounts: On the need to differentiate the effectors of approach/avoidance responses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00563

Krieglmeyer, R., Deutsch, R., De Houwer, J., & De Raedt, R. (2010). Being moved: Valence activates approach-avoidance behavior independently of evaluation and approach-avoidance intentions. Psychological Science, 21(4), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610365131

Kuhl, J., Quirin, M., & Koole, S. L. (2021). The functional architecture of human motivation: Personality systems interactions theory. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 8, pp. 1–62). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2020.06.001

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1990). Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological Review, 97(3), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.97.3.377

Lu, B., Hui, M., & Yu-Xia, H. (2005). The development of the Native Chinese Affective Picture System—A pretest with 46 college students [In Chinese]. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 19(11), 719–722.

McGrew, K. S. (2022). The cognitive-affective-motivation model of learning (CAMML): Standing on the shoulders of giants. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 37(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/08295735211054270

Morelli, S. A., Lieberman, M. D., & Zaki, J. (2015). The emerging study of positive empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12157

Morris, J. S., Friston, K. J., Büchel, C., Frith, C. D., Young, A. W., Calder, A. J., & Dolan, R. J. (1998). A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain, 121(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/121.1.47

Neumann, R., & Strack, F. (2000). Approach and avoidance: The influence of proprioceptive and exteroceptive cues on encoding of affective information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.39

Paulus, A., & Wentura, D. (2016). It depends: Approach and avoidance reactions to emotional expressions are influenced by the contrast emotions presented in the task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000130

Rotteveel, M., & Phaf, R. H. (2004). Automatic affective evaluation does not automatically predispose for arm flexion and extension. Emotion, 4(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.156

Seidel, E.-M., Habel, U., Kirschner, M., Gur, R. C., & Derntl, B. (2010). The impact of facial emotional expressions on behavioral tendencies in women and men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36(2), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018169

Shoumy, N. J., Ang, L.-M., Seng, K. P., Rahaman, D. M., & Zia, T. (2020). Multimodal big data affective analytics: A comprehensive survey using text, audio, visual and physiological signals. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 149, Article 102447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2019.102447

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(3), 220–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1

Wang, J. Z., Zhao, S., Wu, C., Adams, R. B., Newman, M. G., Shafir, T., & Tsachor, R. (2023). Unlocking the emotional world of visual media: An overview of the science, research, and impact of understanding emotion. Proceedings of the IEEE, 111(10), 1236–1286. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2023.3273517

Whalen, P. J., Shin, L. M., McInerney, S. C., Fischer, H., Wright, C. I., & Rauch, S. L. (2001). A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fear versus anger. Emotion, 1(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.70

Wittekind, C. E., Blechert, J., Schiebel, T., Lender, A., Kahveci, S., & Kühn, S. (2021). Comparison of different response devices to assess behavioral tendencies towards chocolate in the approach-avoidance task. Appetite, 165, Article 105294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105294

Arias, J. A., Williams, C., Raghvani, R., Aghajani, M., Baez, S., Belzung, C., Booij, L., Busatto, G., Chiarella, J., Fu, C. H., Ibanez, A., Liddell, B. J., Lowe, L., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Rosa, P., & Kemp, A. H. (2020). The neuroscience of sadness: A multidisciplinary synthesis and collaborative review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 111, 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.006

Ascheid, S., Wessa, M., & Linke, J. O. (2019). Effects of valence and arousal on implicit approach/avoidance tendencies: A fMRI study. Neuropsychologia, 131, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.05.028

Aupperle, R. L., & Paulus, M. P. (2010). Neural systems underlying approach and avoidance in anxiety disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/raupperle

Bamford, S., & Ward, R. (2008). Predispositions to approach and avoid are contextually sensitive and goal dependent. Emotion, 8(2), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.174

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1), 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930

Cacioppo, J. T., Gardner, W. L., & Berntson, G. G. (1997). Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: The case of attitudes and evaluative space. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0101_2

Carr, L., Iacoboni, M., Dubeau, M.-C., Mazziotta, J. C., & Lenzi, G. L. (2003). Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: A relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(9), 5497–5502. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0935845100

Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(2), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025002007

Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M., & Elmehed, K. (2000). Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions. Psychological Science, 11(1), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00221

Duckworth, K. L., Bargh, J. A., Garcia, M., & Chaiken, S. (2002). The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychological Science, 13(6), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00490

Eder, A. B., & Rothermund, K. (2008). When do motor behaviors (mis)match affective stimuli? An evaluative coding view of approach and avoidance reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 137(2), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.262

Fricke, K., & Vogel, S. (2020). How interindividual differences shape approach-avoidance behavior: Relating self-report and diagnostic measures of interindividual differences to behavioral measurements of approach and avoidance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 111, 30–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.008

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). Codes and their vicissitudes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(5), 910–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X01520105

Hoofs, V., Boehler, C. N., & Krebs, R. M. (2019). Biasing actions by incentive valence in an approach/avoidance task. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1), Article 42. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.205

Johnson, E. (2021). Face validity. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (pp. 1957–1957). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91280-6_308

Kozlik, J., Neumann, R., & Lozo, L. (2015). Contrasting motivational orientation and evaluative coding accounts: On the need to differentiate the effectors of approach/avoidance responses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00563

Krieglmeyer, R., Deutsch, R., De Houwer, J., & De Raedt, R. (2010). Being moved: Valence activates approach-avoidance behavior independently of evaluation and approach-avoidance intentions. Psychological Science, 21(4), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610365131

Kuhl, J., Quirin, M., & Koole, S. L. (2021). The functional architecture of human motivation: Personality systems interactions theory. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 8, pp. 1–62). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2020.06.001

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1990). Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological Review, 97(3), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.97.3.377

Lu, B., Hui, M., & Yu-Xia, H. (2005). The development of the Native Chinese Affective Picture System—A pretest with 46 college students [In Chinese]. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 19(11), 719–722.

McGrew, K. S. (2022). The cognitive-affective-motivation model of learning (CAMML): Standing on the shoulders of giants. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 37(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/08295735211054270

Morelli, S. A., Lieberman, M. D., & Zaki, J. (2015). The emerging study of positive empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12157

Morris, J. S., Friston, K. J., Büchel, C., Frith, C. D., Young, A. W., Calder, A. J., & Dolan, R. J. (1998). A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain, 121(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/121.1.47

Neumann, R., & Strack, F. (2000). Approach and avoidance: The influence of proprioceptive and exteroceptive cues on encoding of affective information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.39

Paulus, A., & Wentura, D. (2016). It depends: Approach and avoidance reactions to emotional expressions are influenced by the contrast emotions presented in the task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000130

Rotteveel, M., & Phaf, R. H. (2004). Automatic affective evaluation does not automatically predispose for arm flexion and extension. Emotion, 4(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.156

Seidel, E.-M., Habel, U., Kirschner, M., Gur, R. C., & Derntl, B. (2010). The impact of facial emotional expressions on behavioral tendencies in women and men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36(2), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018169

Shoumy, N. J., Ang, L.-M., Seng, K. P., Rahaman, D. M., & Zia, T. (2020). Multimodal big data affective analytics: A comprehensive survey using text, audio, visual and physiological signals. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 149, Article 102447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2019.102447

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(3), 220–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1

Wang, J. Z., Zhao, S., Wu, C., Adams, R. B., Newman, M. G., Shafir, T., & Tsachor, R. (2023). Unlocking the emotional world of visual media: An overview of the science, research, and impact of understanding emotion. Proceedings of the IEEE, 111(10), 1236–1286. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2023.3273517

Whalen, P. J., Shin, L. M., McInerney, S. C., Fischer, H., Wright, C. I., & Rauch, S. L. (2001). A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fear versus anger. Emotion, 1(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.70

Wittekind, C. E., Blechert, J., Schiebel, T., Lender, A., Kahveci, S., & Kühn, S. (2021). Comparison of different response devices to assess behavioral tendencies towards chocolate in the approach-avoidance task. Appetite, 165, Article 105294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105294

Figure 1. Experiment Workflow

Figure 2. Push–Pull Reaction Time Results for Experiment 1

Note. *** p < .001.

Figure 3. Push–Pull Reaction Time Results for Experiment 2

Note. * p < .05.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

This research was supported by the Chongqing Higher Education Admissions Examination and Enrollment Research Project (CQZSKS2025052), and the Research Project on the Communication Strategies of Mainstream Ideology in the Self-Media Environment (23SKSZ052).

Tong Yue, Research Center for Psychology and Social Development, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected], or Zuoshan Li, School of Teacher Education, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing 40131, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]

Article Details

© 2026 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved.